29 unusual jobs that no longer exist

Outdated occupations that have bitten the dust

PA Archive

Remember pinsetters, lectors and switchboard operators? Robots may be stealing jobs left, right and centre nowadays, but plenty of professions have vanished over the years as society has changed and technology has progressed.

Read on for some once-common occupations from way back when that no longer exist.

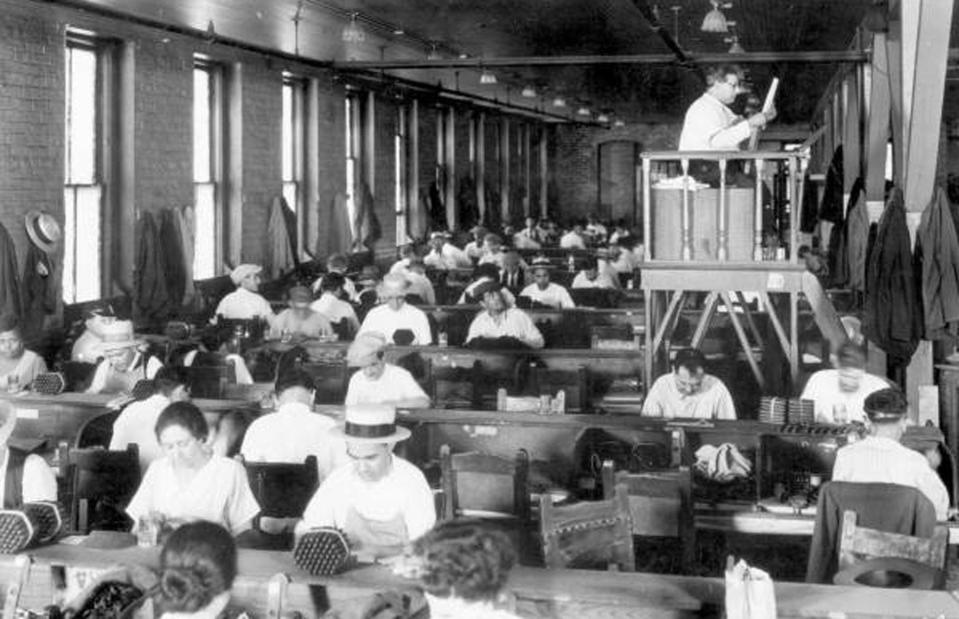

Factory lector

By Burgert Brothers via Wikimedia Commons

From the late 1800s onwards, Cuban cigar factories hired lectors to read mainly left-wing books, newspapers and so on to workers while they rolled away. The custom spread to the US in the early 20th century, but was banned in the country in 1931 by factory owners, who were concerned the lectors were spreading communist and anarchist ideas.

Night soil collector

Nationaal Archief/Collectie SPAARNESTAD PHOTO/W.P. van de Hoef via Wikimedia Commons

This most revolting of occupations called for a weak sense of smell and super-strong stomach. Night soil collectors had the unfortunate job of removing human waste from people's privies. The profession was prevalent in 19th-century America, Europe and Australia before widespread sewerage systems were built, and still survives nowadays in some countries, notably India and Japan.

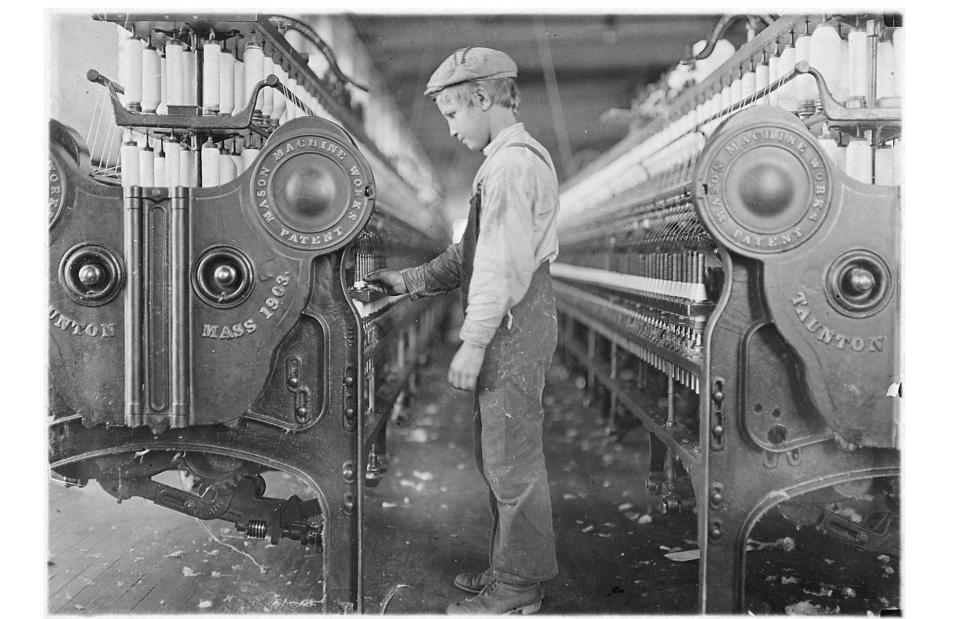

Doffer

Lewis Hine via Wikimedia Commons

Child labour was sadly a fact of life in many Western countries up to and during the early 20th century. Doffers, for instance, were nimble-fingered young boys who worked in textile factories removing and replacing bobbins from the spinning frames, and were a common sight in American mills until 1933, when child labour was finally outlawed.

Rat-catcher

State Library of New South Wales via Wikimedia Commons

A profession straight out of the fairy tale books, rat-catchers used everything from ferrets and terrier dogs to poison and traps to control vermin in villages, towns and cities, but were often accused of covertly raising and releasing rats to boost their workload. These days, their job has long been taken over by pest control technicians.

Breaker boy

Lewis Hine via Wikimedia Commons

Another Victorian profession that has thankfully disappeared, coal breaking entailed separating impurities from coal by hand, and was mainly carried out by children. The work was dangerous and children often cut and burned their hands, and some even lost their lives. Public condemnation grew in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and by 1920 the cruel practice had ended.

Buggy whip maker

NVO via Wikimedia Commons

This ill-fated occupation of yesteryear is often cited by economists as a classic example of how technological progress can kill an entire sector. The buggy whip industry was thriving in the 1890s with thousands of companies producing the essential riding accessory, but had all but vanished by the early 20th century as the automobile replaced the horse and carriage.

Ice-cutter

By John Boyd via Wikimedia Commons

Before air con and refrigeration became widespread, ice cutting was big business in North America and Europe. Cutters would harvest tonnes of ice during wintertime, which would be stored in hay-packed icehouses, then distributed in towns and cities during the heat of summer. At its peak in the late 19th century, the ice trade employed 90,000 people in the US alone.

Iceman/woman

National Archives at College Park via Wikimedia Commons

Ice-cutters harvested the ice, but the blocks were delivered to homes and businesses by icemen, and to a lesser extent icewomen, as you can see from this photo, which was taken in New York during World War I. The trade fell into decline not long after and had all but died out by the 1950s, but ice delivery still happens in Amish communities, which shun electricity.

Gas lamplighter

Arthur Tanner/Fox Photos/Getty

In the late 19th century, the towns and cities of Europe and North America were teeming with gas-powered lamps, and it was the lamplighters' job to fire them up each evening. Gas was replaced by electricity in the early 20th century, but several cities have retained a limited number of gas lamps, including London, which boasts 1,500 lamps and five part-time lamplighters.

Caddy butcher

National Archives and Records Administration via Wikimedia Commons

Caddy butchers specialised in selling horsemeat which, believe it not, was actually pretty popular in the UK and US up until the 1940s. The meat, which was always considered a cheap and somewhat undesirable alternative to beef and venison, has since become completely taboo in English-speaking countries, where it's almost impossible to snap up these days.

Whale meat seller

General Photographic Agency/Getty

Likewise, you won't find any New Yorkers in 2018 who regularly chow down on whale meat, but the delicacy was once enjoyed as an affordable treat by the Big Apple's poor – this photo was taken around 1920. As the denizens of the city became more prosperous, the meat fell out of favour and the trade, in the US at least, has long been consigned to history.

Stoker

By Hudson, F A (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer via Wikimedia Commons

A stoker or fireman was the unlucky individual tasked with tending the fire in the boiler of a steam train, ship or saw mill. The job entailed lots of shovelling coal in horrifically high temperatures, and was not for the faint-hearted. Mercifully, the introduction of electric locomotives, ships and so on in the 20th century rendered the profession obsolete.

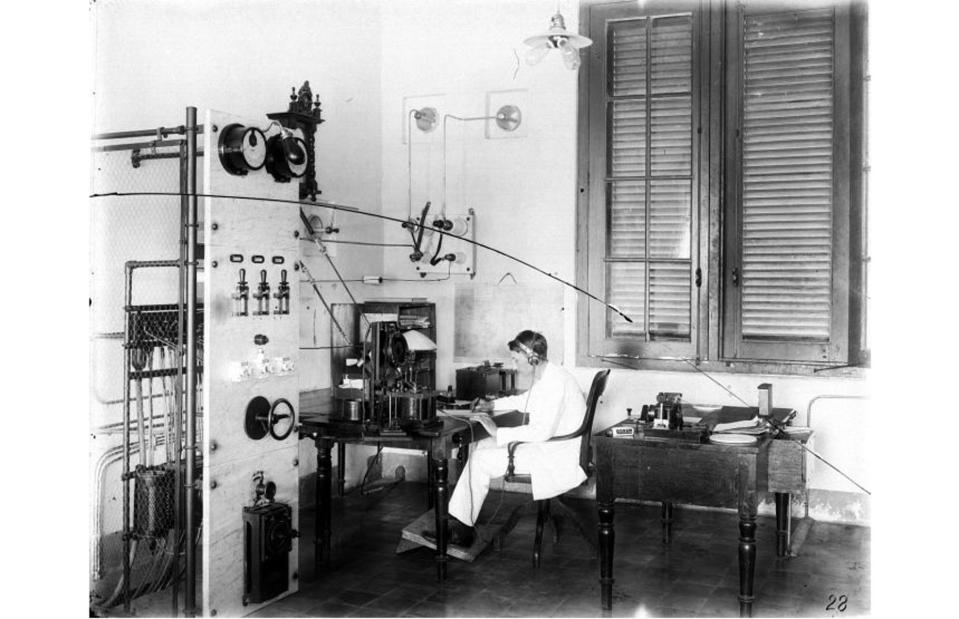

Telegraph operator

Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures via Wikimedia Commons

The electric telegraph was invented in the 1830s and remained the fastest way to communicate over long distances until it was superseded by the telephone in the 20th century. The telegraph operator sent and received the messages, and had to be fluent in Morse code. In return, wages tended to be generous and competition for available roles was fierce.

Telegraph/telegram boy

By Lewis Hine via Wikimedia Commons

In Europe and North America, telegraph or telegram boys were employed to deliver telegrams, which had to be sent or received at a post office or telegraph company like Western Union. The boys, who were usually in their mid-to-late teens, delivered the messages on foot or by bike, and later via motorcycle. The practice lasted into the 1970s in some parts of the UK.

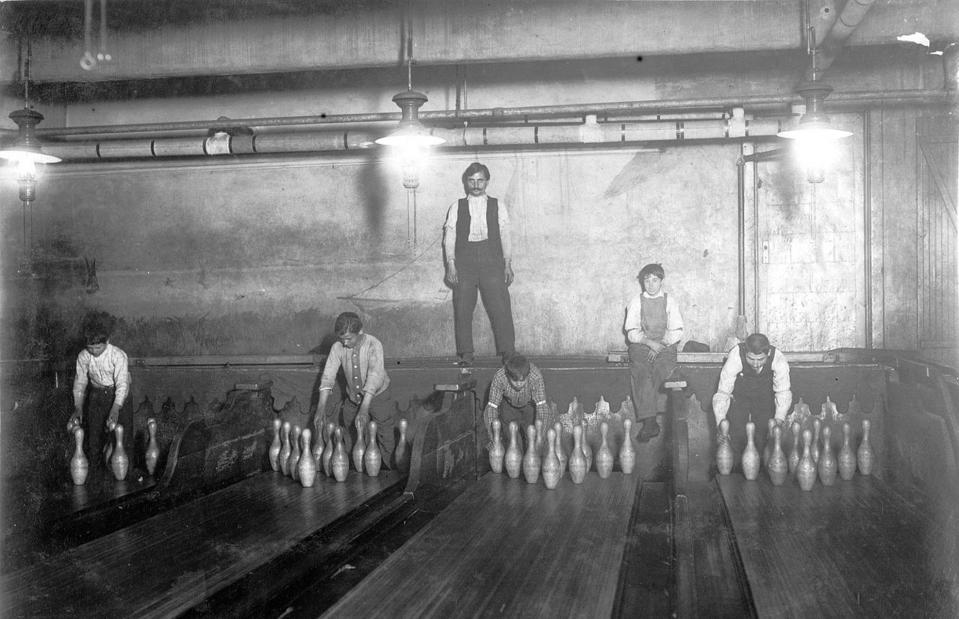

Pinsetter

By Lewis Wickes Hine, 1874-1940, photographer via Wikimedia Commons

Like telegraph or telegram boys, pinsetters were mostly teenaged boys who worked in bowling alleys across North America re-setting pins and collecting balls. The occupation died out rapidly following the invention of the mechanical pinsetter in the 1940s, but a tiny minority of bowling alleys still use manual pinsetters.

Log driver

By User Obli via Wikimedia Commons

Log drivers risked life and limb to move huge quantities of timber downstream in the days before widespread railways and logging roads. Log driving survived in some parts of North America right up until the 1970s, when environmental legislation outlawed it, and is still carried out traditionally on a small scale in northern Spain.

Used teeth salesman

Vaagn Hansen/BIPs/Getty

For much of the 20th century, access to decent dental treatment was limited, particularly in Europe, and many people who couldn't afford to visit the dentist resorted to buying second-hand false teeth when their pearlies had rotted away. The foundation of the NHS in 1948 ended the icky trade in the UK, though it carried on in other parts of Europe for a while longer – this photo was taken in Amsterdam in 1955.

Human computer

Courtesy NASA

Human computers worked for organisations crunching numbers right up until the 1960s. The profession was notably inclusive at a time when science jobs were dominated by white males. Hidden Figures, a 2016 book by Margot Lee Shetterly, tells the story of three Black women – Katherine Johnson (pictured), Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson – who were employed as human computers for NASA, and was the basis of the Oscar-winning movie of the same name.

Linotype operator

By Farm Security Administration via Wikimedia Commons

Linotype machines were used by newspapers and magazines for typesetting from the late 19th century until the 1980s, when computer technology made them defunct. The operators worked long hours in exceptionally noisy composing rooms. The volume in the rooms was so high, the New York Times is said to have favoured hearing-impaired candidates for linotypist positions.

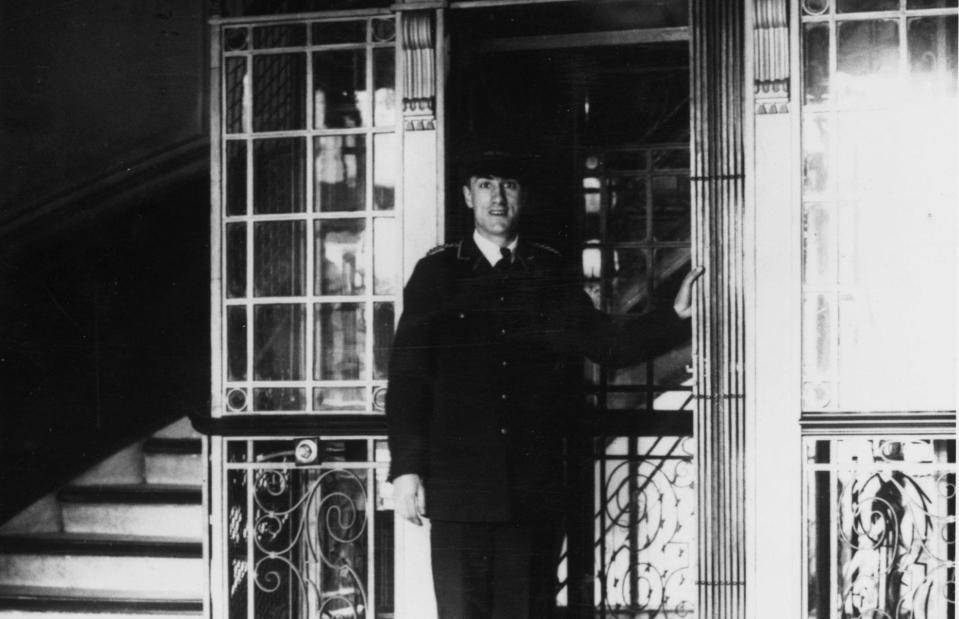

Elevator operator/lift attendant

General Photographic Agency/Getty

During the first half of the 20th century, elevators or lifts were manual and required a human operator. The occupation declined from the 1930s when automatic elevators began to replace the manual models, and only survives today as a luxury novelty in a small number of high-end department stores and apartment buildings.

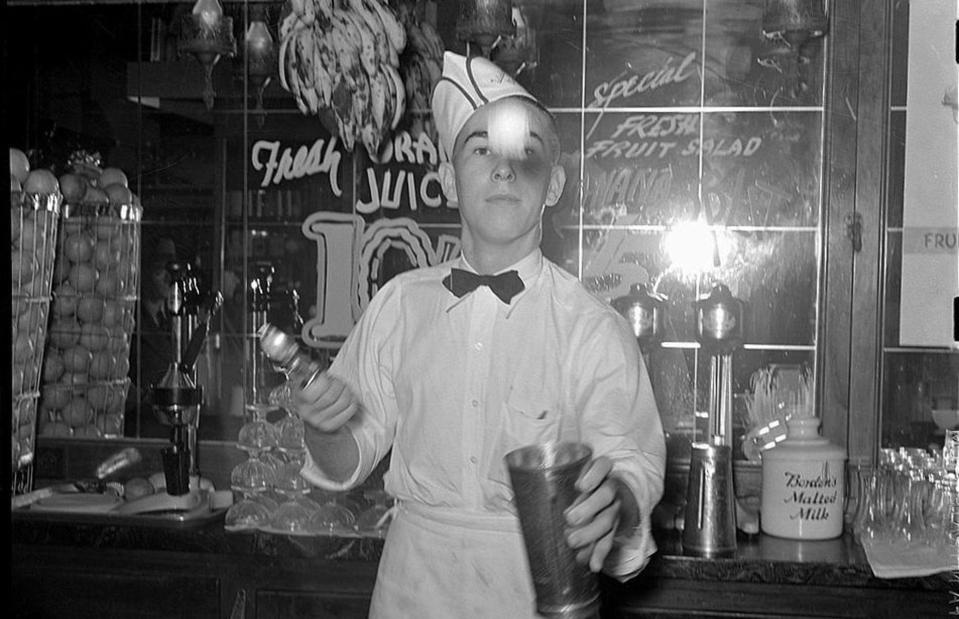

Soda jerk

By The Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

Typically energetic young men with big personalities, soda jerks operated the soda fountains in America's drugstores, and were in charge of whipping up syrup and ice cream sodas for customers. The soda jerking craze kicked off in the 1920s and was popular right up until the 1950s when self-service fast food restaurants and drive-ins arrived on the scene.

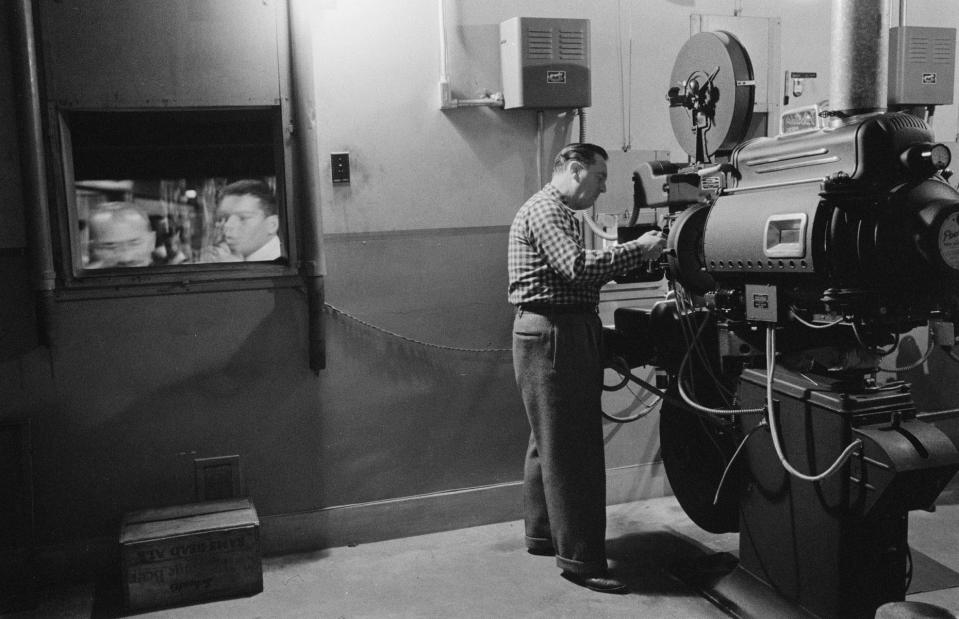

Projectionist

By Trikosko, Marion S., photographer. via Wikimedia Commons

Yet another victim of technological change, the movie projectionist is now a largely defunct role since the introduction of digital cinema projection, which requires very little skill and is performed in many cinemas these days by front-of-house staff who also sell the tickets and popcorn.

Typist

By Archives New Zealand via Wikimedia Commons

During much of the 20th century, companies employed pools of typists to produce and edit documents, until the widespread adoption of computers and photocopiers in the 1980s and 1990s. These days, jobs for straight copy typists are almost impossible to find in Western countries, where admin staff are expected to have a variety of office-related skills.

Encyclopaedia seller

Carsten/Three Lions/Getty

Now that the Encyclopædia Britannica has moved online, the internet has finally killed the hard copy encyclopaedia, along with the infamous door-to-door salesman. Smartly dressed and scarily persuasive, the silver-tongued peddler would sweet-talk unsuspecting customers into parting with large sums of cash for the oversized tomes.

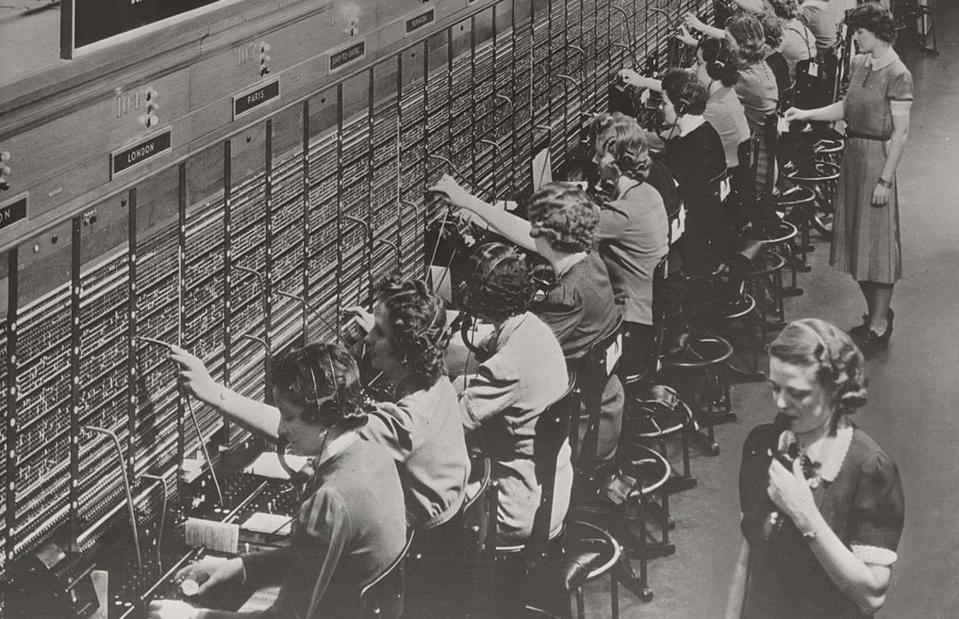

Switchboard operator

By The U.S. National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

“Operator, please connect this call” was a frequently uttered phrase back when phone companies had manual switchboards. The operators, who were mostly women, inserted a phone plug into the relevant jack to connect a call. Automated switchboards were widely adopted from the 1960s onwards, and by the 1980s the profession had all but vanished.

Video store clerk

David Friedman/Getty

Thanks to online streaming, the days of dealing with snooty video clerks who sneer at your movie picks and berate you for not rewinding the cassettes are long gone. Blockbuster, for instance, employed 84,300 staff at its peak in 2004 and counted 9,094 locations. Nowadays, the retailer has just one store left, in Oregon, after its two remaining Alaska stores closed in summer 2018.

Knocker-upper

Courtesy Beamish Museum

Back in the days when alarm clocks were pricey and unreliable, knocker-uppers would do the rounds each morning and wake factory workers by banging on their front doors with a heavy stick or similar implement. The profession, which was common in the industrial cities of Britain and Ireland during the 19th and early 20th centuries, didn't actually die out until the 1950s in some places.

Muffin man

PA Archive

Do you know the muffin man? In the UK, this cheery hawker would go from house to house at breakfast time carrying a tray of freshly-baked English muffins on his head. The practice continued well into the 20th century in some cities. This photograph of a London muffin man was taken in 1924.

Rag-and-bone man

Peter Trimming/Flickr CC

Brits of a certain age will fondly remember the rag-and-bone man, who would roam the streets with his horse and cart, ringing his bell, and collecting junk from grateful residents. By and large, the practice died out in the 1980s, when many of the UK's remaining rag-and-bone men moved into the scrap metal trade.

Now check out these surprisingly dangerous jobs

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance