Age-old notions of the noble savage haunt views of working-class life

There are few things more fractured and muddled than contemporary attitudes towards working-class people. On the one hand, too many people ignore, even deny, the grim realities of working-class lives, of the problems of poverty and precariousness. On the other, many seek to appropriate the seeming authenticity that comes with being working class, identifying as such even when they are not.

Three studies last week reflected the disjointedness of the way the working class is perceived. The first was a report from the Office for National Statistics that showed that, over the past decade, median income for the poorest fifth of the population fell by 4.8% to £13,800, mostly in the last four years, while that of the richest fifth increased by an average 0.7% a year to £62,400.

An important reason for the fall in the income of the poorest was austerity, including the benefits freeze introduced in 2016. Even the Financial Times recognises that such policies were misguided and that now “the aim of balancing the budget can, at least temporarily, be dropped”. In Downing Street, though, no lessons seem to have been learned. The chancellor, Rishi Sunak, appears to have resurrected Theresa May’s infamous “there is no magic money tree” line to justify his refusal to maintain the £20 universal credit uplift introduced at the start of the pandemic.

A Resolution Foundation report last week suggested that cutting the £20 increase would lead to the incomes of the poorest households falling by at least 4%, and would put the basic level of unemployment benefit in real terms at its lowest level since 1991. As the Resolution Foundation’s Torsten Bell observed, any such cut “takes us back not to an OK ‘normality’ but to widespread destitution”. The government’s reluctance to introduce decent levels of benefits, whether universal credit or sick pay, is rooted not just in an obsession with “balancing the books” but also in an ingrained prejudice that the problem of poverty itself really lies in the moral failings of the poor.

From Iain Duncan Smith imposing a benefit cap to teach parents that “children cost money”, to MP Ben Bradley complaining that free school meals vouchers were “effectively” used to fund “crack dens and brothels”, to another Tory MP, Bim Afolami, suggesting last week that “the best way of getting people out of poverty is into work” (ignoring the fact that more than two million claimants on universal credit are in work), demonising the poor has been a central feature of government policy.

Yet, while there is widespread contempt towards the poor, there is also a pervasive social desire among people who are not working class to be seen as having working-class origins. The 2016 British Social Attitudes report, for instance, showed that nearly half of those in managerial and professional jobs saw themselves as working class, including 24% of professional people whose parents were also professionals. Last week, an academic paper by sociologists Sam Friedman, Dave O’Brien and Ian McDonald explored the reasons for such misidentification. They interviewed 175 people in managerial and professional jobs, more than one in five of whom identified as working class.

They do so to create “elaborate ‘origin stories’” that “downplay important aspects of their own, privileged, upbringings” and allow them “to tell an upward story of career success ‘against the odds’” that “casts their own achievements as unusually meritocratically legitimate”.

The desire to be seen as working class may seem to be at odds with the demonisation of the poor. In fact, it’s part of the same process. It’s a way of people viewing themselves as “strivers”, not “shirkers”, to use the language of former chancellor George Osborne, as possessing both the authenticity of a humble background and the nous to escape it.

Implicit here is the suggestion that those who are in precarious or low-paying jobs, or are unemployed, have only themselves to blame for not having the wherewithal to escape their background. Meritocracy becomes the means both to create the illusion of working-class roots for those who have become middle class and to demonise as insufficiently go-getting those left behind. They are the “left behind” in the sense of being victims not of globalisation or deindustrialisation or austerity but of their own moral, cultural and intellectual deficiencies.

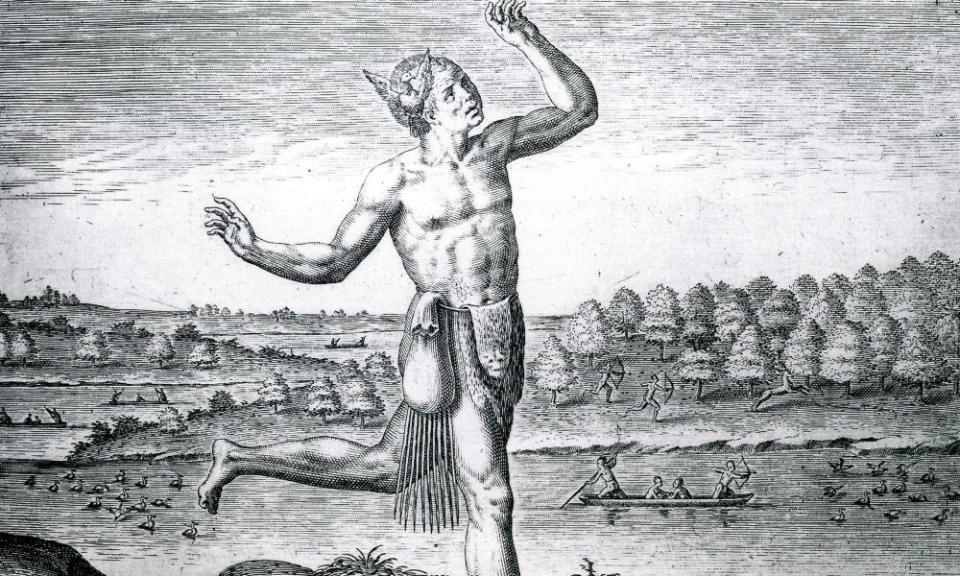

In the 18th century, European intellectuals often viewed Native Americans and Pacific Islanders as “noble savages”, people both lauded for the authenticity of their lives and berated for their primitivism and lack of civilisation. Today, it often seems that sections of the working class play a similar role in the national imagination.

Kenan Malik is an Observer columnist

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance