Ailing Hedge Funds Turn to Brazil’s Hot Private-Credit Market

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s hedge funds and equity funds are turning to private credit as stubbornly high interest rates force them to grapple with rising redemptions and shifting investor preferences.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Saudis Warned G-7 Over Russia Seizures With Debt Sale Threat

The End of the Cheap Money Era Catches Up to Chelsea FC’s Owner

S&P 500 Tops 5,600 Mark in Longest Rally This Year: Markets Wrap

Verde Asset Management SA, one of Brazil’s oldest and most venerable hedge funds, is among asset managers launching their first-ever credit funds. Others include equity fund house Drýs Capital, formerly known as Equitas, and private equity investment firm EB Capital Gestão de Recursos Ltda. It’s an effort to adapt to a new reality: Credit vehicles are luring away their customers.

“We need to deliver good risk-adjusted returns to our clients, and in recent years the hedge fund and equity fund industries had important challenges in relation to this,” Luiz Parreiras, a partner at Verde, said in an interview. “So we are rethinking processes, rethinking what we can do to deliver those good returns.”

Private credit gained traction globally after the 2008 financial crisis as an alternative to banks at a time when regulators were clamping down on risky lending by deposit-taking institutions. Higher interest rates in the US are helping make returns more attractive. The market there hit $1.5 trillion this year, compared to $1 trillion in 2020, according to a June Morgan Stanley report, which estimated that it may reach $2.8 trillion by 2028.

In Brazil, the market expanded when policymakers began aggressively hiking interest rates in 2021 to fight inflation, forcing companies to seek cheaper funding outside banks and offering investors the juiciest returns. Hedge funds then started to struggle to beat a higher benchmark. Verde, which had 55 billion reais ($10 billion) in assets under management in 2021, now has 22 billion reais.

An index that tracks the performance of hedge funds in Brazil was nearly flat for the first six months of the year, its worst first half since 2020 and lagging behind the 5.2% gain for the benchmark CDI rate over the same period. In comparison, an index for plain-vanilla, less risky corporate bonds returned 7.29%.

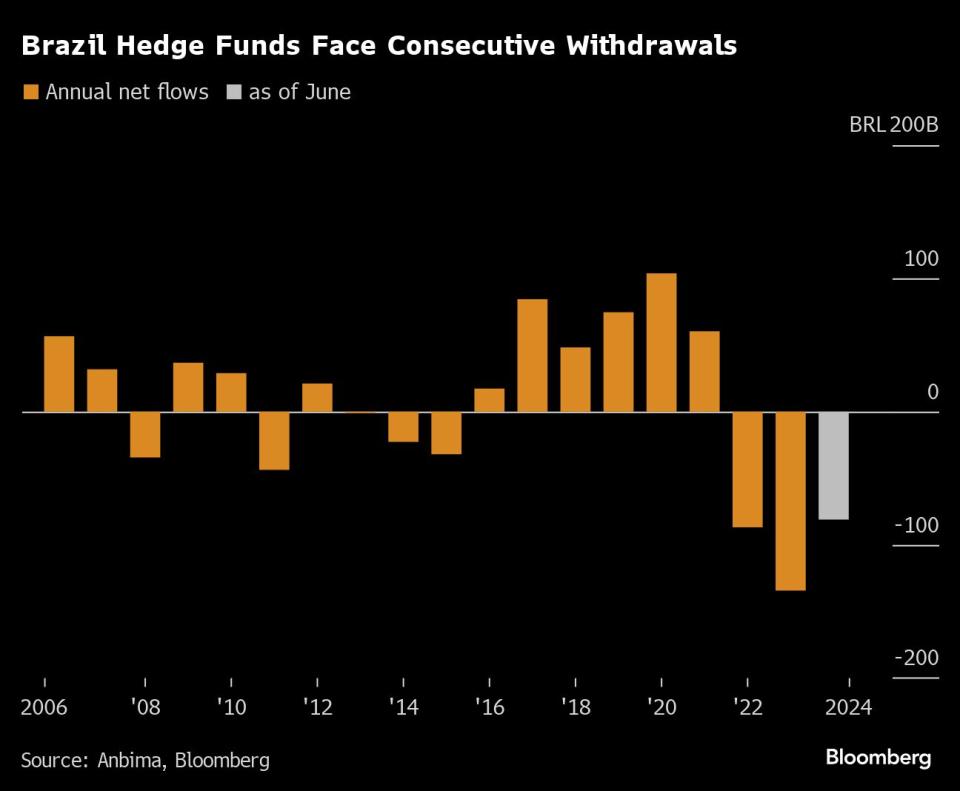

It’s not just poor performance that’s been drying up demand for hedge funds, which had net outflows of 81 billion reais in the first half of this year, according to Anbima, the nation’s capital-markets association. A new rule increased the tax burden on rich investors using exclusive funds to invest in hedge funds, while cutting taxes for private credit funds.

Equity funds, suffering along with Brazil’s slumping stock exchange, had 100 million reais of withdrawals as the benchmark Ibovespa stock index dropped 7.66%.

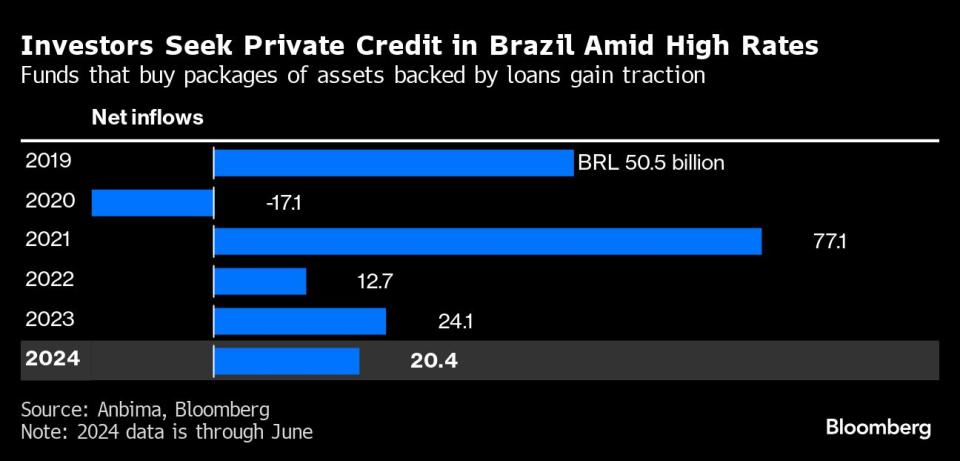

In contrast, so-called FIDCs — funds that represent part of Brazil’s private-credit industry — had net inflows of 20.4 billion reais. FIDCs, which exist only in Brazil and are similar to the US securitization market, are funds that invest in credit packages, with shares sold to investors in tranches that can be separated by risk.

“FIDCs are rising stars, and now that regulators allow retail clients to invest in them, the market is going to explode,” said Samer Serhan, a partner at Brazilian credit-fund manager Jive Investments, which has 18.5 billion reais in assets. He was referring to a change the market regulator made last October.

Some investors in FIDCs are getting into a complex market they may not totally understand, experts cautioned.

“Each FIDC is different from the others, and their structures are not obvious, they are very tough to analyze,” said Ricardo Binelli, a partner at Solis Investimentos, which has about 16 billion reais under management. Understanding those details is key to managing risk, he said. His firm is preparing to launch a FIDC that will buy shares of other FIDCs, aimed at mom and pop investors.

Rafael Fritsch, a partner and chief investment officer at Root Capital, agrees. “Just because someone knows how to trade equity doesn’t mean they know how to invest in credit,” he said. “To buy credit you need a neurotic mindset, to think all the time that you may lose.”

High interest rates bring opportunities to buy credit at attractive returns, but also raise default risks, said Marcelo Mifano, head of special situations at Vinci Partners Investments Ltd., one of Latin America’s biggest alternative-asset managers.

Verde started investing in credit in 2006, through its hedge funds, and has being building experience and teams ever since. In May, it launched a FIDC dubbed Ipe, named for the tree in South and Central America known for its extremely solid wood. It will initially be distributed only on platforms run by Banco BTG Pactual SA for institutional and qualified investors. The goal is to reach 1 billion reais by the end of 2025, Parreiras said.

Also in May, Luis Stuhlberger, Verde’s founder and one of the most revered hedge fund managers in Brazil, was put in charge of the firm’s local stock funds after almost half of the team departed. Verde’s next plan is to launch a fund that buys tax-exempt infrastructure bonds, according to Parreiras.

FIDCs can buy credit from smaller companies that pay interest rates many times higher than the basic rate, and by doing so their returns are more attractive than funds investing in plain vanilla bonds, which are facing compressing spreads amid booming demand. Issuance of those bonds more than doubled to 204.2 billion reais so far this year from the same period in 2023, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That contrasts with the equity market, where the last initial public equity offering by a Brazilian company was 2 1/2 years ago.

Brazil’s structural high interest rates are “very bad” for the stock exchange, and the number of companies planning to issue equity is very small, reducing buying opportunities for funds, said Luis Felipe Amaral, founding partner at Drýs Capital. Previously called Equitas, the firm changed its name in May to take into account the new credit business, Amaral said.

Porto Asset, an arm of Brazilian insurance company Porto Seguro SA, with 32.5 billion reais under management, cut part of its equity team and moved other parts to focus on fixed-income funds, given the perception that the negative scenario for risky assets “could last a little longer,” said Chief Investment Officer Izak Benaderet. The company signed a strategic partnership with SFA Investimentos, an independent asset manager, which will manage most of Porto’s equity funds.

“There is still a huge space for banking disintermediation in Brazil,” said Marcello Almeida, partner and head of credit at Vinci. “The higher interest-rate scenario contributes even more to this thesis, creating all the conditions for private credit to grow.”

--With assistance from Vinícius Andrade and Felipe Saturnino.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance