The Anatomy of a Dip: How to Buy Low in Today's Markets

You've probably heard the term "buy the dip" thrown around by more than one market analyst, especially in recent months. Quick, buy Tech Stock A after a 5% decrease because it will soon go back up! The idea is one that is loosely based on the basic principle of value investing: buying low and selling high.

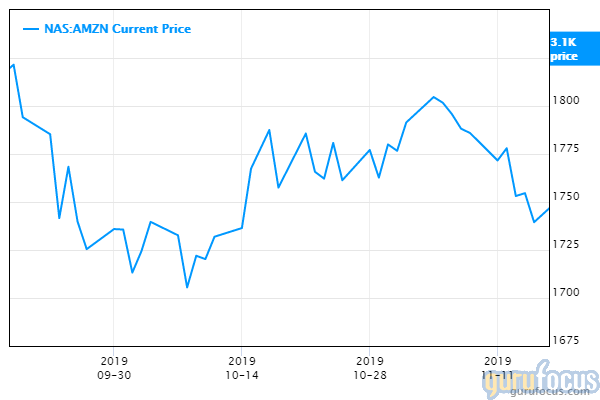

However, the term seems to be directed broadly at any decrease in price for a company that the investing community is generally bullish on, from the 1% decline in Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) after its third-quarter earnings fell short of analysts' expectations to the 30% that Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) tanked during the coronavirus-related market crash in February and March.

So, what use is the advice to buy on dips if a "dip" can be any price decrease whatsoever? Let's take a look at when buying a dip can be profitable, when it is virtually meaningless and when the so-called dip is the result of Mr. Market interacting with inexperienced retail traders, index funds and algorithms rather than long-term investors.

Mr. Market's mood swings

There is a difference between buying a dip in a stock that is the result of a true undervaluation and buying what some analysts will call a dip, despite there not really being a significant enough price change or an undeserved reason for said price change.

The father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, created the character of "Mr. Market" to illustrate how investors can take advantage of true mispricing in the markets to earn stellar returns:

"One of your partners, named Mr. Market, is very obliging indeed. Every day he tells you what he thinks your interest is worth and furthermore offers to either to buy you out or to sell you an additional interest on that basis. Sometimes his idea of value appears plausible and justified by business developments and prospects as you know them. Often, on the other hand, Mr. Market lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes seems to you a little short of silly.

If you are a prudent investor or a sensible businessman, will you let Mr. Market's daily communication determine your view of the value of a $1,000 interest in the enterprise? Only in case you agree with him, or in case you want to trade with him. You may be happy to sell out to him when he quotes you a ridiculously high price, and equally happy to buy from him when his price is low. But the rest of the time you will be wiser to form your own ideas of the value of your holdings."

In other words, buying the dip only really works if Mr. Market quotes you a price that is significantly lower than your own carefully researched intrinsic value estimate for the company.

One prominent example of a dip was back when investors sold shares of government health insurance providers like Centene (NYSE:CNC) in 2018 out of fear that expanded access to health care in the U.S. would cut into their profits, despite the fact the relatively few people who actually worked in and understood the business knew that any losses would most likely be outweighed by gains from the premiums of new (mostly healthy) customers. Indeed, as you can see in the chart below, both revenue and net income continued to increase throughout 2018, 2019 and the beginning of 2020, and investors who bought the dip had the opportunity for as much as a 50% return in less than a year.

Knee-jerk reactions

In addition to deeper mispricing, there are times when a stock only drops a small percentage in response to news or media coverage that really has nothing to do with the underlying business.

For example, companies often see their share prices drop if they fail to meet analysts' predictions for earnings per share or revenue, even if they sill achieved growth year-over-year. Conversely, companies that beat analyst expectations can see share prices rise despite seeing less business.

If investors were to "buy the dip" in these situations, they would end up seeing virtually no difference than they would if they had bought slightly before or after the dip. This is not a long-term investing strategy, but a form of speculation, and a poor one at that.

For an illustration, let's return to the previously mentioned example of buying the dip for Amazon in the third quarter of 2019. On Oct. 24, Amazon released earnings results that fell short of analyst expectations. The next day, all but one analyst covering the company recommended buying the 1% dip in the stock price that followed. By Nov. 15, prices had dropped a whopping 2% compared to the Oct. 24 levels. Regardless of whether you bought during the dip or within a month before or after, your return would be about 80%, give or take a couple tenths of a percentage point. There was no temporary mispricing here.

Imagine that instead of buying the 1% dip on Amazon, you had bought the 14% dip on Hertz (NYSE:HTZ) after it reported better-than-expected earnings for its third quarter of fiscal 2019. That wouldn't have worked out nearly so well because, as with the 1% Amazon decline, it was not the result of a true mispricing. For the strategy of "buying low and selling high," neither of these cases represented a true dip.

Retail, index and algorithmic pricing

There is a third type of dip in stock prices that is related to neither Mr. Market's mood swings nor the knee-jerk reactions of investors to unimportant news, analyst calls and the like. This type of dip results from the rise in popularity of retail trading, index trading and algorithmic trading. What these three things have in common is they often result in dramatic, uncontrollable and unpredictable changes in stock prices.

As online brokerage firms cut fees to remain competitive with new players, the entry barrier for retail and hobby traders has lowered, resulting in retail investors accounting for nearly 25% of the stock market's activity in the first half of 2020 compared to only 10% in 2019. The lower barrier encourages individuals with low income or little stock market education to try their hand at investing, often resulting in unpredictable price changes and more investing dollars going to speculation or beloved companies.

In September of 2019, the amount of money in index funds surpassed the amount of money in actively managed funds for the first time in U.S. history. In the past, the U.S. economy has only grown over a long enough time frame, so more and more investors are preferring the low-effort option of committing savings to index funds and letting them be. However, when the low-effort passive index fund begins dropping steeply, individuals and pension funds alike may be inclined to withdraw their money all at once to avoid losses, making the decline even steeper.

Last but not least, we have algorithmic trading. Some algorithms are incorporated into index trading as a common feature of passive accounts is to automatically convert the entire investment to cash as soon as prices drop sharply enough. Enterprising investor mathematicians have also developed various computer models and algorithm networks in an effort to achieve market-beating returns. The most famous example of this type of investor is Jim Simons (Trades, Portfolio), the founder of Renaissance Technologies, also known as "The Man Who Beat the Market."

Retail, index and algorithmic investing can all cause significant and meaningful price changes in the markets. These changes are sometimes predictable, but all too often they manage to blindside investors who are focused on a various combination of company fundamentals and macroeconomic factors, leaving out how the ever-increasing amount of liquidity in the markets leads to higher volatility and, in some cases, more permanent mispricing.

Conclusion

"Buying the dip," or buying low with the expectation that you are getting a good deal on a valuable equity security, can be extremely profitable for investors. It is certainly better than buying high and later selling low due to panic or the realization that prices will only continue falling.

However, before buying the dip, it is important to consider what caused it. Is it a legitimate mispricing due to widespread fear or an economic downturn that does not actually affect the business conditions or fundamentals? Is it a knee-jerk reaction from an earnings report or some other news? How much is it exacerbated by index trading, algorithmic trading or retail traders chasing high yields or a flashy stock?

Disclosure: Author owns no shares in any of the stocks mentioned. The mention of stocks in this article does not at any point constitute an investment recommendation. Investors should always conduct their own careful research and/or consult registered investment advisors before taking action in the stock market.

Read more here:

Not a Premium Member of GuruFocus? Sign up for a free 7-day trial here.

This article first appeared on GuruFocus.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance