Coming to America's Arsenio Hall: 'In the 90s I was black Twitter'

“So I’m watching this guy and I’m like: ‘All he has is a glass of juice … and his braaaain,’” says Arsenio Hall, who is in the middle of a five-minute anecdote about a conversation he once had with a man called Hank. I didn’t ask about Hank, but here we are, talking about his marvellous bonce. I’m speaking to Hall because he’s back as Semmi, the supercilious man servant to Eddie Murphy’s King Akeem in Coming 2 America, the long-awaited sequel to the 1988 comedy. But more on that in a minute – we need to get back to Hank.

When he met Hank who, he enthusiastically recalls, was from Ypsilanti, Michigan (“These details you never forget when it changes your life!”), Hall was a young magician from Cleveland with a dove act, while Hank was a seasoned operator, who once managed to entertain a crowd of Al Green fans with his comedy chops and a glass of juice he used as a prop.

After their performances, Hank sat the young Hall down for a life-changing chat. “Hank says: ‘I love to hear you talk, young man. One day you’re going to get rid of those birds, and you’re going to make your living by talking.’”

Hank was right: Hall would ditch the doves and become a groundbreaking talkshow host, the first black person to have their own national late-night vehicle in the US. In the era of Jay Leno and David Letterman, Hall would be the hipster’s choice of late-night frontman, with a young and fanatical following who came to him for loud clothes, up-to-date guests and Hall’s own convivial hosting for its five-year run.

More than 25 years since the show first went off air (it was rebooted in 2013 but axed after one season), Hall still likes to talk. More specifically he likes to tell stories, meandering ones that are rooted in his talkshow heyday. From his home in Los Angeles, he tells me about the time he booked an unknown MC Hammer after approaching him outside a hotel (“I kind of broke a single for Hammer”). There’s the tale of how his hero, talkshow legend Johnny Carson, recommended a young Usher to him (“[Carson’s people] gave me two names: Usher, Raymond”). And the time he got into a scrap with producer, Paramount, when he tried to get NWA on his show (“Ice Cube gave me this tape, and it said ‘Fuck tha Police’ in Sharpie … Paramount was like: ‘There’s no way that’s gonna happen’”). As host, Hall would “constantly push for the stuff I liked, that I thought America didn’t know about”.

It’s an absorbing potted history of an innovative show and, at a time when the likes of Trevor Noah and Eric Andre are playing with the late-night rulebook, it serves as a reminder that Hall paved the way. “Something that I would whisper to you that I probably shouldn’t say out loud, is that now I see a lot of people – black and white – doing things that I started,” he says. “I really do think that I kind of broke the mould a little bit, and allowed people to do it their way.”

Hall says his career has been a series of happy accidents, but in reality he worked hard to craft those opportunities from an early age. As a child he admired Carson so much that he started practising magic and playing the drums because his idol had. He wrote in to The Tonight Show and tried to get himself booked as an 11-year-old (his mother kept the polite rejection letter for him). When he followed Hank’s advice and switched to standup comedy in Los Angeles, he took every opportunity he could, including filling in for Joan Rivers, who had just quit her talkshow on Fox. That successful spell as interim host led to his big, career-defining break: The Arsenio Hall Show.

It is easy to forget now but in the late 80s and early 90s, Hall really did shift the needle on late night. Here was a 32-year-old without a huge profile prior to its launch, suddenly his show was bringing in $50m a year for Paramount, who picked up the series after Fox passed. In 1992 when, then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton wanted to cement his reputation among young voters it was on Hall’s show that he famously chose to showcase his saxophone-playing. “[Hall] had a lock on the youth crowd, especially younger women,” wrote Bill Carter in his classic account of late-night television, The Late Shift. “Within months Hall was a phenomenon.”

But things didn’t last. “Like many acts that start off sizzling hot, Hall’s was tough to sustain with the hip crowd, who never finds anything hip for the long term.” With ratings low and the competition from Leno and Letterman intense, Hall stepped away from the show in the spring of 1994. “I just tried to create my own world,” says Hall of the show’s run. “I saw a void, and I tried to exploit that void.”

The other world Hall helped create was Zamunda, the fictional African country that Prince Akeem leaves to find a wife in Coming to America. Released at the peak of Eddie Murphy mania, the film was a huge hit, ending up the third-highest grossing film of 1988 in the US. Murphy and Hall are back for the sequel along with new additions such as Tracy Morgan, Leslie Jones and Jermaine Fowler, whose characters travel to Zamunda in a reversal of the first film’s fish out of water storyline.

The version of Africa the sequel presents is an opulent place where elephants walk around perfectly manicured lawns and excess is par for the course. But the original film has been criticised for presenting Africa as “a place of feudal hierarchy [and] pre-feminist sexual politics”, and the sequel is unlikely to silence critics, given an arranged marriage and patriarchal control are central to proceedings.

Hall seems genuinely perplexed by the criticism the original received. “You never saw positive images of black people on television when we were young,” he remembers. “Look, when a person like Trump gets to say what he thinks [about Africa], you hear words like ‘shithole’. We wanted to show the motherland as beautiful.”

So the jokes weren’t at the expense of Africans? “We wanted to make the people intelligent, wealthy and all these positive things along with the comedy and the love story,” Hall adds. “You’re gonna get criticised, but our purpose was to do really positive things.”

One of the criticisms that Hall continually faced in his talkshow-host career was that he was a lightweight, keener to have a laugh with the people he had on his sofa than get under their skin. Perhaps the most notorious example cited by critics is his sitdown with Louis Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam leader notorious for his antisemitic views – which he denies – including blaming Jews for everything from paedophilia in Hollywood to slavery. Hall says he prepared for Farrakhan’s appearance by asking the leader of the Jewish Defense League to help him craft the questions. He knew the risks, he says, and ultimately the interview was a chance to ask Farrakhan about topics such as the murder of Malcolm X, to which he has always been linked. “When he says something like he may have contributed to the atmosphere that killed Malcolm X, I never heard him say something like that before. And I thought that was important,” says Hall.

The LA Times didn’t agree, dismissing the interview as a “rout”. The incident, and the theory that it was what led to the show’s cancellation, has dogged Hall ever since, despite the fact that, keen to move away from the notoriously demanding world of late night, he had sent his resignation letter months before he booked Farrakhan.

“If you go in a barber shop now and you ask why The Arsenio Hall Show in the 90s got taken off the air, most people will not tell you: ‘He wrote a resignation letter because he wanted to do other things,’” says Hall, who sounds genuinely annoyed about the rumours. “‘He actually wanted to have a kid, and he wanted to act, and late night occupies every moment of your time.’ [Instead] if you go into a barber shop, they’ll tell you: ‘Y’know, white man took them off there because he interviewed that Farrakhan.’”

I try to move off the subject, but he comes back for another bite. “I’m probably not working today – in somebody’s mind – because of that interview, but, y’know, it just raises the wall for me and I’ve been jumping over walls all my life, so I’m good,” he adds, while not actually sounding that good. Still, Hall remains proud of his show’s legacy. He tells another story about the time he booked Bobby Brown and convinced execs to let him open the show with Don’t Be Cruel. One rule of late night was that you didn’t open with a musical number, which traditionally came toward the end of the show. But Hall did it anyway.

The more humble Hall falls away for a second as he recalls the impact that his bold choices made. “There was no YouTube, you couldn’t go pull up this and that or Google things. I was like Twitter spreading the shit,” he says. “I wasn’t a blue bird, I was a black bird: I was black Twitter.”

Even Hank might not have predicted that.

Coming 2 America is available on Amazon Prime Video

Hall of fame: five memorable Arsenio guests

Madonna (1990)

Hall caught Madge at her peak, both in terms of fame (just prior to the Blond Ambition tour) and capacity for outrage. On pugilistic form, she quizzed her host on his breakup with Paula Abdul, hinted at a romantic tryst between him and Eddie Murphy and even mocked his haircut (“No fades. It’s tired”). Hall, for once, was almost speechless.

Vanilla Ice (1991)

Genuine grillings were a rarity on Hall’s show, but he couldn’t resist taking aim at the rapper over some sketchy aspects of his backstory. Their tense face-off would be described by Entertainment Weekly as “nine of the most onerous minutes in television talk show history.”

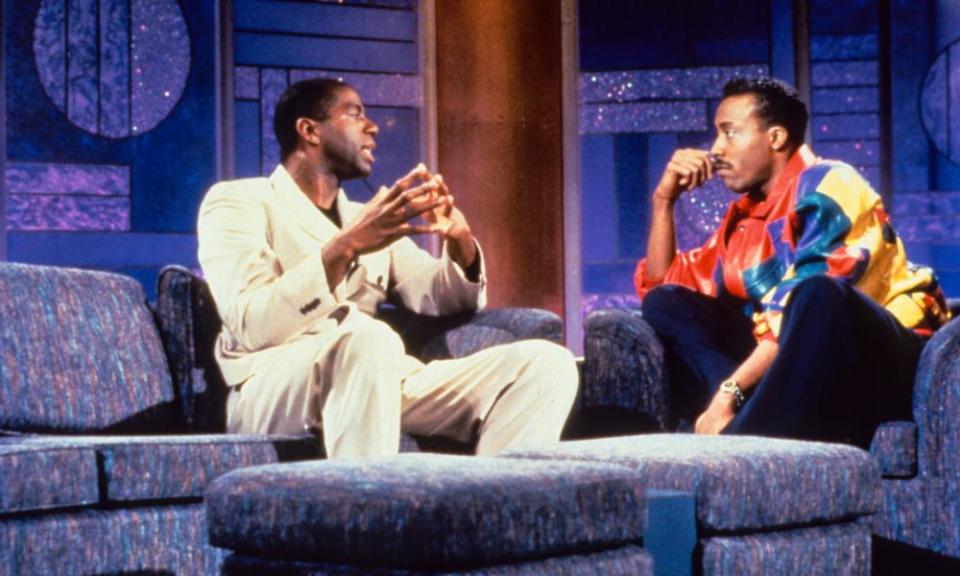

Magic Johnson (1991)

NBA star Earvin “Magic” Johnson’s announcement that he was HIV positive served as a seismic cultural moment in the US, and it was inevitable that he’d choose close friend Hall to conduct the first interview in its wake. The pair would reunite for an information film on the virus a year later.

Bill Clinton (1992)

Looking to position himself as a hip alternative to presidential rival George HW Bush, Clinton rocked up with his sax. (“Good to see a Democrat blowing something other than the election,” Hall quipped.) Mocked at the time, it’s now seen as a game-changer for how politicians interact with the world of entertainment.

RuPaul (1993)

RuPaul considers his late-night debut as a breakthrough moment, when “the whole world got to see me”. He regaled the audience with tales of standing up to the Ku Klux Klan in full drag, quips such as “I’m a regular Joe … I just have the unique ability to accessorise”, and a barnstorming rendition of his hit single Supermodel (You Better Work). Gwilym Mumford

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance