Australia’s anti-war movement is depleted – who will stop the march to the ‘drums of war’?

A war with China would be unthinkable – but no one should believe it couldn’t happen.

“Many estimate that we have three to five years before conflict begins.” That was the grim message from senator Jim Molan in his recent piece for the Australian.

We might dismiss such prognostications as an effort by a former military leader to scare up some more defence spending. Yet Molan correctly identifies the underlying dynamic of the US-China relationship: namely, an ongoing struggle for regional influence between a United States in economic decline and an increasingly ascendant China.

As he says, “the second-most powerful nation (China) wants to overtake the most powerful nation (the US). This has happened 16 times in the past 500 years and war has resulted on 12 of those occasions.”

The University of Sydney scholar David Brophy argues that the long-term Australian reliance on US power in the Asia Pacific makes local elites particularly terrified about the consequence of a US withdrawal from the region. As a result, the rhetoric from Australian politicians and military leaders might be seen as directed as much at the Americans as at the Chinese – an attempt to goad Biden into a more aggressive stance.

In a way, though, that doesn’t really matter.

In politics, the mask becomes the face. Irrespective of intentions, rhetorical posturing becomes genuine belligerence once it’s understood as such by the other side.

In a deeply unstable situation, verbal confrontations take on a momentum of their own, particularly with the leaders of both powers pandering to constituencies hopped up on nationalist bluster.

And that’s not the biggest reason to worry.

Lack of vibrant left spells danger

The post-911 invasions should have proved – if any proof were needed – that military intervention only worsens conditions for people living under oppressive regimes. The campaign against the Taliban did not liberate the women of Afghanistan; the overthrow of Saddam Hussein plunged Iraq further into misery.

Yet, once again, some on the left have fallen in behind the rhetoric of the right; persuaded by the oppression in Xinjiang, the brutality in Hong Kong and the general authoritarianism of the Chinese rulers, some of those who might be counted on to oppose war have come to believe that there’s something progressive in backing a military buildup.

As a result, the resources upon which an anti-war movement might draw are much depleted, ideologically and organisationally.

The danger in the current moment doesn’t, then, pertain simply to the strength of the forces pushing towards a confrontation between two nuclear armed nations but also to the weakness of those who would prevent it.

Eighteen years ago, we saw how a relatively small group of neoconservatives, initially centred on the Project for the New American Century, could make war happen, gradually persuading most of the western elite to back their unhinged plans for Iraq.

Their real opposition came from elsewhere.

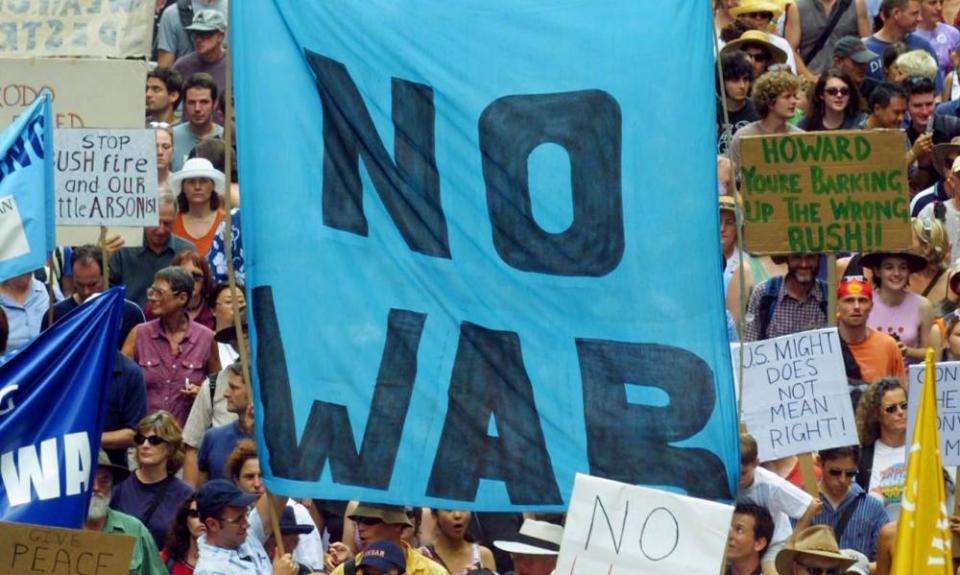

On 15 February 2003, about 10 million people took to the streets of hundreds of cities across the world. Contemplating the largest one-day anti-war mobilisation in human history, Patrick Tyler from the New York Times wrote of a clash between the “two super powers on the planet: the United States and world public opinion.

.In that showdown, the US eventually prevailed, unleashing a catastrophic invasion that killed hundreds of thousands of people and set in train a series of disasters are still reverberating around the region.

That’s why there’s no room for complacency.

Today’s militarists understand that the anti-war campaigns of the past relied on the organisational muscle of the trade unions – and that unions are at their weakest state in 150 years. They also know that the social movements arising from the new left of the 60s have more of a presence in universities and NGOs than they do on the streets.

So who will stop the march to conflict?

In the next period, the tension between Australia, the US and China will almost certainly increase, with more of the now-familiar tit-for-tat provocations. The lack of a vibrant left makes the situation extraordinarily dangerous, with the more gung-ho politicians feeling little pressure to restrain themselves.

That’s why we should take Molan seriously.

He wants three to five years to prepare for war.

The same brief timeline applies to those who want peace. If we are to prevent this madness, we need to get organised – and quickly.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance