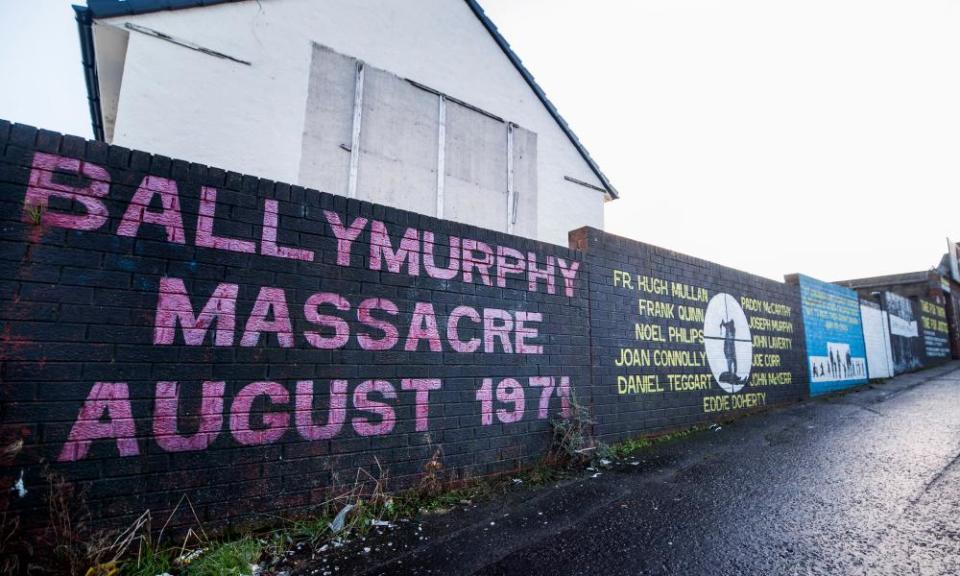

The Ballymurphy shootings: 36 hours in Belfast that left 10 dead

Even by the standards of Northern Ireland’s Troubles it was a tumultuous, violent couple of days.

The British army swept into nationalist neighbourhoods across the region on the morning of 9 August 1971 as part of Operation Demetrius, rounding up hundreds of suspects without trial in the hope of snuffing out the IRA’s campaign.

The army intelligence was poor – they scooped up many innocent people – and they ignored loyalist paramilitaries. Some neighbourhoods responded with barricades, petrol bombs and gunfire. Hundreds of homes were destroyed and thousands fled across the border to refugee camps set up by the Irish army.

In Ballymurphy, a Catholic district in west Belfast, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment’s 2nd Battalion commandeered a community centre known as the Henry Taggart memorial hall.

The next 36 hours were chaotic, bloody and left 10 people dead, 11 if including a man who had a heart attack after an alleged mock execution. Unlike Bloody Sunday in Derry five months later, there were no TV crews or newspaper photographers to record events in Ballymurphy.

The troops maintained they targeted armed terrorists, with perhaps some civilians caught in crossfire. Residents told another story of soldiers raking their homes with gunfire and picking off unarmed people, then shooting those who came to their aid.

Several residents gave statements, documented in a 2014 Guardian investigation, in which they described being pinned down on open ground. When one man, Robert Clarke, was shot in the back, a neighbour took two nappies from a woman taking cover and waved them in the air.

Father Hugh Mullan, a parish priest, phoned the army to say soldiers were shooting at people fleeing their homes. Waving a white handkerchief, he then dashed out to give the last rites to Clarke.

Kevin Moore, a seaman on leave who was sheltering nearby, saw the priest being shot twice: “He screamed and drew his knees up in front of his stomach and seemed to curl up in a ball.”

Terence McIlharvey said in his statement that Mullan prayed in English and Latin, then went quiet. “During this 10 minutes shots were still coming in very fast especially when anybody moved.”

As Mullan lay dying, another man, Frank Quinn, 19, attempted to help Clarke. He was shot in the head and killed.

Soon after, another group of people who were gathered opposite the Henry Taggart memorial hall came under fire.

Joan Connolly, a mother of eight who had vocally protested against the army’s incursion, was shot dead, along with Noel Phillips, 20. Five men were wounded and were brought into the hall by soldiers. Two of them – Joseph Murphy, 41, and Daniel Teggart, 44 – died of their wounds.

One who survived, David Callaghan, said in a statement he had been kicked and clubbed with rifles and that the wounded men in the hall were treated only when an army padre insisted.

One soldier known as “Soldier E” when he gave his statement said he had shot three people, including Connolly. He said she had been armed with what appeared to be a pistol. Swabs of the dead woman’s hands suggested she had not fired a weapon. Soldiers recovered no weapons from any of the 10 dead.

Soldiers fired so many rounds they ran low on ammunition. A soldier who resupplied them, Harry Gow, then an 18-year-old paratrooper, wrote in a book published in 1995 that the soldiers inside the hall “were on a high” when he arrived.

“As soon as I walked in I understood why. Six bodies lay sprawled at the bottom of a raised stage. One of them was a woman, hit at least three times.”

When asked as to what he meant by a “high”, Gow said it was because the soldiers had survived an armed action.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance