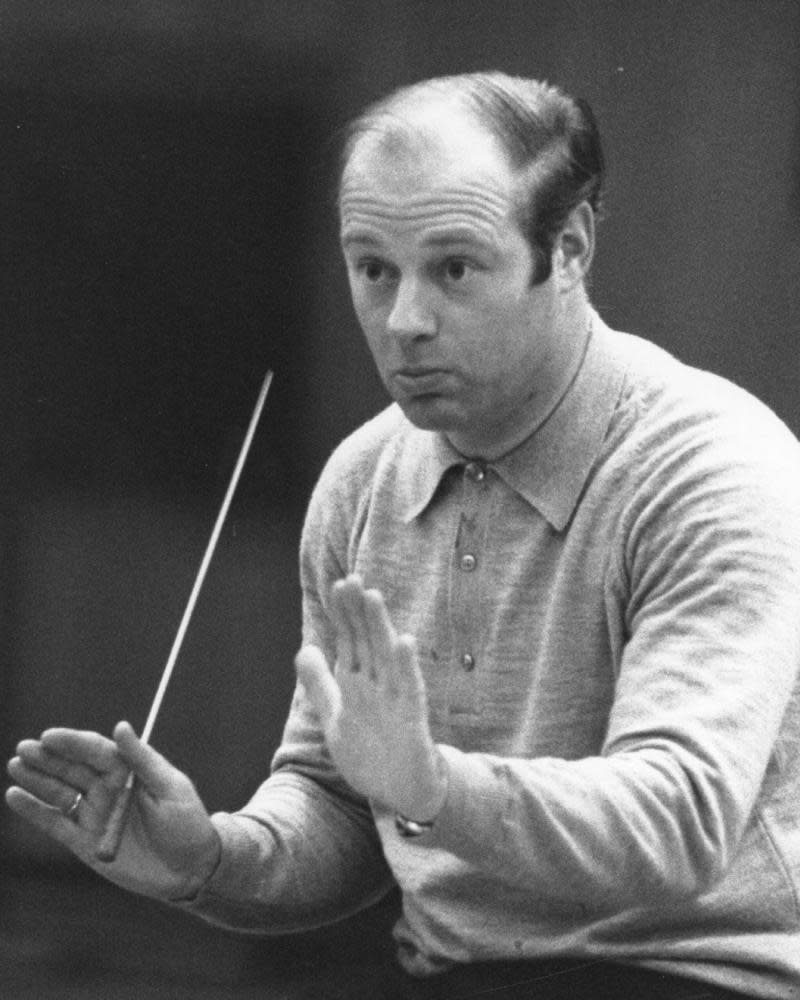

Bernard Haitink’s direct, refined conducting made him a true master

It’s just over two years since, at the age of 90, Bernard Haitink made his final appearance in London, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic at the Proms in two of the composers closest to his heart throughout his 65-year career on the podium, Beethoven and Bruckner. The virtues of those performances, their clarity and insight, and their utter lack of anything showy, epitomised Haitink’s strengths as an interpreter, which guaranteed his place in the pantheon of 20th-century conductors.

British audiences were especially privileged for more than half a century to have had so many opportunities to appreciate Haitink’s gifts in the concert hall and opera house, beginning with his period as the principal conductor of the London Philharmonic from 1967 to 1979, then through his musical directorships at Glyndebourne (1977-88) and at the Royal Opera House (1987-2002), and finally in the relationship he established in his later years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He’d been part of my personal concert-going life in London from the 1970s, when he was one of a group of outstanding conductors – along with Claudio Abbado, Pierre Boulez, Georg Solti among others – who frequently worked in the capital; all of them would have been exceptional in any era, and I doubt any of us realised then how lucky we were to be able to hear them so regularly.

His critics would say that in comparison with some of his contemporaries, Haitink’s repertoire was unadventurous and narrow. Certainly during his years at the ROH he conducted no Puccini, relatively little Verdi (though his performances of Don Carlos were tremendous), and steered well clear of the bel canto repertoire. But for his admirers, his commitment to Mozart, Wagner and Janáček especially, more than made up for that. He avoided contemporary music, rarely conducting any composer later than Shostakovich, but he did also explore some 20th-century British music. His recordings of Elgar and Vaughan Williams symphonies still stand up well, and at Covent Garden he did conduct both Britten’s Peter Grimes and Michael Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage at Covent Garden.

In their distinctive, refined way, his performances of Debussy and Stravinsky were sometimes exceptional too, but it was as an interpreter of the mainstream symphonic repertoire from Beethoven to Mahler that he excelled with every orchestra he conducted, whether it was the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Dresden Staatskapelle, or the Boston or Chicago Symphonies. He’d been one of the prime movers in the Mahler revival of the 1960s, completing a recorded cycle of the symphonies with the Concertgebouw Orchestra as early as 1971, and recording the Bruckner canon in the same period too, all performances that half a century on seem as convincing as ever.

But if I had to choose just one Haitink performance that encapsulated his greatness it would be the account of Mahler’s Third Symphony that he conducted with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Barbican in London in 2004. The Third was always a work that suited his musical virtues of directness and structural integrity exceptionally well; that performance, so eloquent, so superbly played and without a moment of self-regard, conveyed them incomparably. And in my experience, the man himself was like his music-making, serious, sincere and direct; he was never one for grand public pronouncements or attention-seeking gestures. There were times, especially when he was at Covent Garden during its difficult years in the 1990s, that a higher public profile and more obvious involvement in solving its problems might have been welcomed, but it always was the music that mattered to him, and he always put that first.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance