Fear swirls around Brexit hitting the lifeblood of Northern Ireland’s economy

As Britain’s departure from the European Union draws closer, discussions about the economic future of a post-Brexit Northern Ireland are increasingly getting fraught with tension over specific concerns.

The Ulster Farmer’s Union sent a fresh warning on Friday about the extent to which a no-deal Brexit would “devastate” the region’s farming sector. It “would be disastrous” if the cliff-edge scenario warned about in the UK’s technical advice papers came to pass, it said.

From every angle—and seemingly no matter what the chain of events—Northern Ireland will be disadvantaged. Monday’s admission from chancellor Phillip Hammond that Britain would have to enforce border checks if the country fails to negotiate a deal with the EU confirms what many in Northern Ireland have been saying for months.

Tuesday’s statements about the Good Friday Agreement from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which in addition to being Northern Ireland’s largest political party, props up prime minister Theresa May’s government in Westminster, only underline the chaos that surrounds the UK’s negotiating strategy.

Even then, last month’s report from the Migration Advisory Committee, which seemed to pay no heed to the specifics of the Northern Irish economy, set off very particular alarm bells. The report, which is likely to form the basis of the government’s upcoming white paper on immigration, recommends a drastic limitation of the post-Brexit immigration of low-skilled workers in any scenario that allows the UK to control immigration.

“They clearly do not understand that whole sectors of the Northern Irish economy depend on this class of workers,” Conor Patterson, chief executive of the Newry and Mourne Enterprise Agency, told Yahoo Finance UK. “This is the type of thing that puts whole communities at odds with central government,” he warned.

There is a reluctant acceptance that a UK-wide seasonal labour scheme will be needed for on-farm employment. But beyond that, the food processing and manufacturing sectors are likely to be razed by an inability to hire low-skilled workers—and they may have no choice but to move south of the border to Ireland.

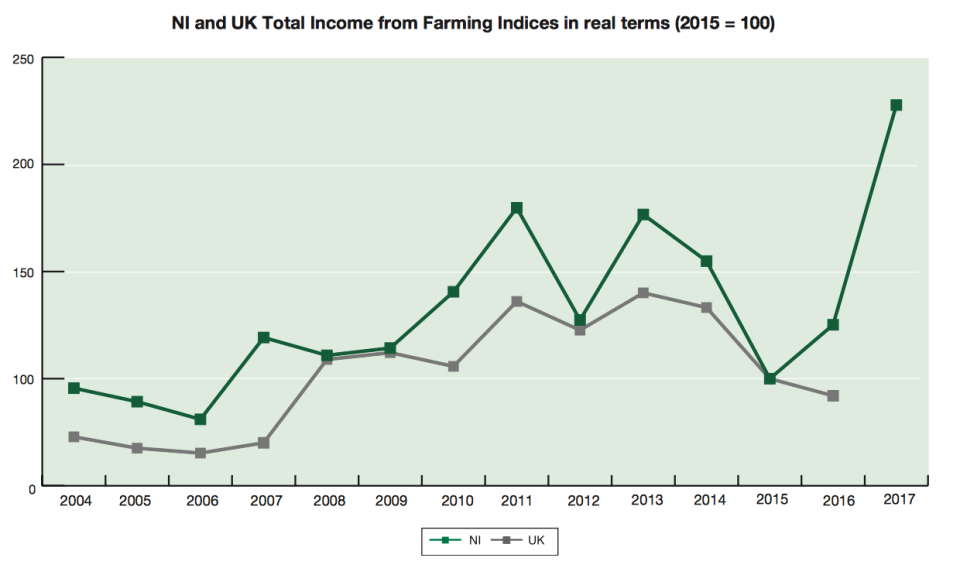

Agriculture is more than three times more important to Northern Ireland’s economy than it is to the UK overall.

“You obviously can’t move on-farm work to the Republic anyway, because it has to be done on the farm,” said Blair Horan, a member of the UK expert group of the Institute of International and European Affairs.

“But what you have are plenty of firms that do light manufacturing, collating and distribution—but employ a lot of people—that can be moved very easily south of the border. This is clearly going to have a huge impact.”

Northern Ireland has a proud manufacturing history associated mainly with the building of ocean liners, aircraft, and tractors. But food products lead the charge today.

Moy Park, an enormous poultry manufacturer based in Craigavon in County Armagh, reported an annual turnover of £1.51bn in September—making it Northern Ireland’s largest company. The second-largest is a grain importer, and another three of Northern Ireland’s top 10 companies by turnover are food or agriculture related.

Because of its size and the fact that it has a US owner, Moy Park has issued stark warnings about Brexit. But the nature of the political situation in Northern Ireland, however, means that most companies are more likely to route their grievances through representative organisations, rather than be seen as part of the “diet of negativity” that DUP leader Arlene Foster warned about on Tuesday.

“Despite the fears, people are still unwilling to come out and say anything they might be pulled up on by one party or the other now or in the future,” said Anthony Soares, the deputy director of the Centre for Cross Border Studies.

The Northern Ireland branch of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), which speaks on behalf of 190,000 UK businesses, said that restricting low-skilled immigration “risks damaging labour shortages.”

But for Patterson, it goes further than that. “It actually risks social instability. Migrant workers not only form a huge part of our workforces, but have become part of the fabric of our communities,” he said.

However good a trade deal with the European Union, there are undoubtedly going to be impacts. Even if Northern Ireland somehow manages to stay within the bloc’s customs union, regulatory checks on agricultural goods may still have to be carried out. Technological checks or inland inspections have continually been ruled out by both Ireland and the EU. The political impacts—considering Northern Ireland’s history—are separate again.

But the workers situation, however, could also require checks, Patterson notes. “Employers may simply choose not to comply with these immigration rules. How is non-compliance going to be policed? And where are checks going to take place?

“This is just one of the things that’s going to lead to absolute compliance chaos,” he said.

The Migrant Advisory Committee suggests that, rather than instigating a specific immigration regime for Northern Ireland, some form of clever investment strategy could go some way to solving things.

But that is a medium- to longer-term project, said Horan, who is also a member of the the EU’s Interreg committee, which has been promoting investment in Northern Ireland for years. “We are trying to develop high-end manufacturing in Northern Ireland, in terms of research and development. But that doesn’t happen overnight.

“In the meantime, you have jobs and businesses that need to survive. None of this is addressing the shorter-term problems that are going to arise. Literally, there is a labour force available south of the border that isn’t available north of the border—and the inevitable consequences are obvious.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance