Brexit: UK businesses are already facing recruitment crisis as Polish workers head home

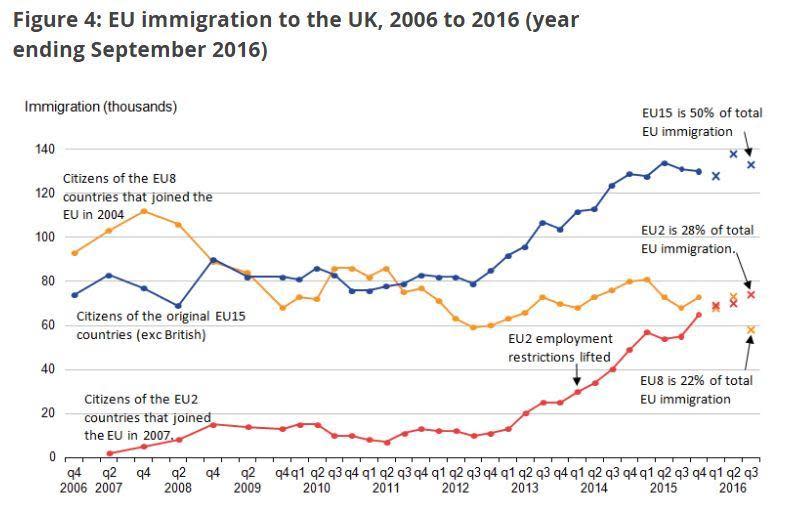

More than 100,000 EU citizens left Britain in the three months after the EU referendum, new figures showed this week.

New worker registrations from Poland are down 16 per cent year on year, Hungary down 14 per cent, and Slovakia down 20 per cent.

After a Brexit vote in which a primary concern was too much immigration, some might be applauding the trend, but for important UK industries it is already creating a serious problem, and one that provides a preview of what may be to come for the wider economy.

While more people are still arriving than leaving, businesses worry the numbers will not be enough to fill vacancies.

The UK’s growing hospitality sector should be a Brexit winner. A record 37 million tourists visited in 2016 as the pound plunged. But many hotels, restaurants and bars are already finding it tough to recruit the EU nationals that make up a large proportion of the industry’s 4.9 million workers.

While the weakened pound means a juicy discount for wealthy American or Chinese visitors dining at the Ritz or stocking up on designer brands in West End boutiques, it also hands a 15 per cent pay cut to the largely foreign workers that tend to those tourists’ needs.

The Government’s lack of clarity on the future of EU migrants in the UK is also damaging, says Ufi Ibrahim, chief executive of the British Hospitality Association.

“People don’t want to pack up their lives and move to the UK if they could end up having to go back again very soon.” Ibrahim says. It’s not only waiters and bartenders who are put off. Even top chefs are turning down jobs in London, Ibrahim says.

“Then there is that sense of being unwelcom”, something which has been fuelled by damaging statements from government ministers, she adds.

Millions of pound of taxpayers' money spent on efforts to encourage people to come to the UK through organisations like Visit Britain and the British Council will “all be flushed away” if ministers don’t adopt a welcoming tone towards migrant workers, Ibrahim says.

Further down the food supply chain, agriculture has an even more acute problem. John Hardman runs Hops Labour Solutions, which recruits around 12,000 of the country’s 85,000 seasonal farm workers, almost all of whom are from Eastern Europe, primarily Romania and Bulgaria.

In 14 years in the business he says that he had never had a problem finding willing hands, but in the July to September following the referendum the flow of migrants from Eastern Europe into the fields of East Anglia, Kent and the Midlands slowed, leaving him with 400 positions left unfilled.

This was in the summer season and problems are worse in winter. The devalued pound has made the prospect of “picking Brussels sprouts at minus 4 degrees in December with a sideways wind” even less attractive than it was before, he says.

“There’s only so sexy you can make that job. The same applies to hacking meat in an abattoir for 40 hours a week.”

Hardman believes the shortfall is increasing. So far in 2017 he has seen a 30 per cent rise in farms needing his services, he says.

“What this tells me is that those farms that were recruiting themselves are now struggling to find the workers. It’s a big uplift year-on-year.”

Problems had begun before the referendum. The first wave of migrants to fill Britain’s fruit-picking fields from the eight countries that joined the EU in 2004 moved on to other jobs once their aspirations rose and the same is now happening with the EU’s latest additions from Romania and Bulgaria, Hardman says.

Brexit has significantly hastened the process after a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment left scars that have yet to heal.

“The Romanian press love a story of a Romanian having a good thrashing in Birmingham,” Hardman says. Such attacks are rare and the post-referendum spike has apparently ended, but people’s memories are long, he says.

Romanians and Bulgarians are still arriving, but not in great enough numbers to replace the previous wave of migrant farm workers who've moved on.

Beverly Dixon, head of human resources at G’s, one of the largest vegetable producers in the UK, says the company has had to work much harder this year to recruit the 2,500 temporary workers it needs.

“Even though these guys are seasonal, they’ve had guaranteed work year after year but now they think they’re not going to be able to come here in two year’s time so they are heading to Germany, Holland and even Norway instead,” Dixon says.

G's operation also supports 1,600 permanent jobs here. "Those could all be in trouble if we cant get the temporary workers", she says.

There is an apparently simple solution to this dilemma: hire more UK workers.

But that's not possible, Dixon says. G’s land in Cambridgeshire is in an area of almost full employment. No one locally is going to give up their full-time job for a seasonal one.

Hardman agrees. “We pick strawberries in Kent where almost no one is unemployed. How do I get those on social welfare from Hull to work down there? And where do I house them?”

The problem is the same in the hospitality industry, where many vacancies are in the South-east.

“Any restriction on availability in an economy where we are nearing full employment is very, very concerning; it’s a high risk,” Ibrahim says.

Nationally, despite concerns about migrants taking jobs, unemployment stands at just 4.8 per cent. It has only dipped lower for two brief periods in the past 40 years. The workforce participation rate is also at a record high.

Hospitality and agriculture, with their high dependence on migrant labour, are the canary in the coal mine. Fashion and textiles, retail and social care all rely on talent from overseas.

James Reed, chief executive of Reed, one of the UK’s biggest recruitment agencies, says vacancies have hit record levels.

“With high employment and such a large number of opportunities on offer, the UK jobs market has turned into a seller’s market. If candidates from the EU are put off from applying for jobs in the UK due to Brexit, then the scales could tip even further,” he said.

There are solutions to the looming labour shortage but none will plug the immediate gap caused by a sharp drop in inward migration.

The British Hospitality Association is working hard with Government to raise the profile and prestige of careers in hospitality so that they attract more British workers. It promotes the industry in schools and backs apprenticeships and training, with the aim of putting hospitality on a par with other professions, as it is in other European countries, but Ibrahim says this is at least a ten-year plan, requiring a significant cultural shift.

In a speech in Tallinn earlier this week, Brexit Secretary David Davis said “it will be years and years before we get British citizens to do those jobs” in sectors requiring low-skilled labour.

For farm work, both Hardman and Dixon are calling for a programme of temporary work visas for people from countries outside the EU, such as Ukraine and Turkey.

In the same speech David Davis seemed to back that idea, but it will be difficult to square with the desire for greatly reduced immigration that was one of the major factors behind the victory for the Leave campaign.

The alternatives to using migrant labour were rarely mentioned on the campaign trail – either British agriculture moves abroad or, somewhat ironically, more British workers will have to start picking Brussels sprouts at sub-zero temperatures in December.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance