How Waterstones booksellers thrived where Amazon’s algorithm failed

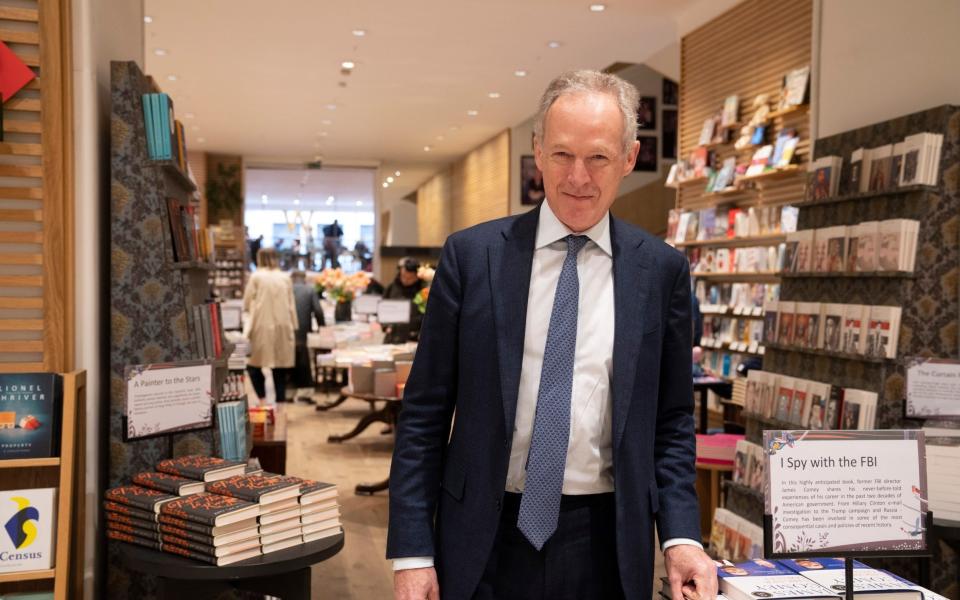

James Daunt used to liken Amazon to a lion that threatened to devour the book industry whole, so potent was its threat to high street shops.

Yet today the softly spoken Englishman can finally boast something his online nemesis can’t: almost four years into running US giant Barnes & Noble, he is preparing to open dozens of new stores – and some in places where even Amazon was forced into retreat.

It is the culmination of a turnaround strategy that Daunt imported wholesale from Waterstones, the British chain he also saved from oblivion.

Both companies are owned by Elliott Management, the infamously ruthless fund manager founded by Wall Street billionaire Paul Singer. Elliott parachuted Daunt in to run Barnes & Noble after buying the struggling chain in 2019.

Under Daunt, the American giant – the biggest US bookstore chain with more than 600 stores – has slimmed down its head office, nixed marketing deals with publishers and put power back in the hands of local branches.

Though the company no longer publishes full financial results, Daunt says the changes have pulled it back from “death’s door”, when it struggled to break even, to making “good money” again.

Pleasingly for anyone who loves reading, his success rests on filling Barnes & Noble shops with a curated choice of books that customers actually want.

As at Waterstones, customers who walk into each branch of Barnes & Noble are now greeted by a display of titles chosen by that shop’s staff. Many are adorned with hand-written recommendations from booksellers.

Alison Baverstock, professor of publishing at Kingston University, says this more personalised approach – borrowed from independent bookstores – is the secret to the revival of Barnes & Noble and Waterstones.

“The key to effective recommendation of books is if people say to you, ‘You'll really like this, or if you like that, you'll also like this’.

“It's much more persuasive than saying ‘Here's our best selling choice, which is based on statistics’.”

Daunt’s use of indy bookseller tactics speaks to his roots: the 59-year-old founded Daunt Books on Marylebone High Street in 1990, setting up in a “picture perfect” Edwardian shop that has become a mecca for book lovers visiting London ever since.

The success of Daunt, which eventually became a small chain, did not go unnoticed. After visiting another one of his branches, Russian businessman Alexander Mamut asked Daunt to take over at Waterstones in 2011. The successful turnaround led to Waterstones being sold to Elliott in 2018.

When Elliott asked Daunt to repeat his trick at Barnes & Noble, the company was in dire straits. Competition from Amazon forced it and rivals into retreat and led Barnes to shut more than 400 bookstores.

In a desperate bid to boost sales, it had also started trying to sell items such as bottled water and batteries displayed in large piles near checkouts.

Daunt feared the situation would only get worse when the Covid pandemic struck in early 2020, forcing Barnes & Noble to close its shops under lockdown. Yet it was a crisis that he now views as a great stroke of luck.

With no customers to serve, it gave staff an unprecedented opportunity to redesign their stores, literally book by book.

“We used that period of closure to effectively rip the stores apart,” Daunt says, “to take all the books off the shelves, move the furniture around and change the layout.”

One aspect of this was trying to make Barnes & Noble stores feel less like “bix boxes”. Many of the shops are between 25,000 and 30,000 square feet – bigger than a typical Waterstones – and tended to resemble libraries, with “row after row after row of book stacks,” he says.

Staff made them cosier, cutting them up into nicer spaces for customers to explore by re-arranging bookshelves to create “rooms” for different subjects such as history, cookery, manga, romance and so on. At the same time, the chain cut the number of books on technical subjects and focused on those most likely to interest the general reader, adding comfortable furniture to create a more congenial atmosphere.

Critical to all of this, says Daunt, was giving booksellers the power to decide what did and didn’t work in their own branch.

Staff were told to use their common sense when deciding how much prominence to give to certain subjects. For instance, the religion section in a metropolitan area like central Boston should probably be smaller than the one in, say, Alabama – but it is ultimately up to local booksellers to decide.

This ethos of putting booksellers in charge was the central pillar of the turnaround at Waterstones and Daunt says he has transplanted “everything” from that success story to Barnes & Noble.

That ranges all the way from local-level policies to big corporate ones, such as axing so-called “co-op” deals with publishers.

Historically, these saw publishers hand book shops millions of dollars up front in exchange for them placing huge orders for titles and guaranteeing they would be displayed prominently. Publishers liked them because it effectively allowed them to guarantee a certain number of sales.

Daunt likened it to crack cocaine, because in exchange for a quick cash payment, all of the company’s branches had to fill their shelves with a potentially poor-quality title.

“Now our booksellers fill their bookshops with the books people want to buy, not the books that somebody in the executive suite in New York thinks that they should,” he says.

This has resulted in the number of returns plummeting too, as was seen at Waterstones. Whereas Barnes & Noble had a returns rate at the top end of 20-30pc in 2019, it now has one that is “comfortably in single digits”.

The pandemic prompted many people to rediscover reading and when stores reopened, customers returned in bigger numbers than ever before, says Daunt. Many are also now spurred on by new social media trends such as “Booktok”, where influencing stars urge their followers to try certain titles.

Daunt’s success is all the more satisfying given it has come as Amazon, the lion in the market, has hit a rare bum note. The giant opened some real world stores where the choice of titles was curated by a robotic computer algorithm – based on what was already selling well online. However, the company has now closed a string of shops – including two in Boston where Barnes & Noble is now expanding.

The personal touch matters in book shops, it seems.

“We want to create spaces congenial to browsing, to exploring books,” says Daunt.

“If you run good book shops, you just need people to come into your shops to discover you. And if you remain a really good book shop, you'll keep them.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance