Central banks have hatched a get-rich-quick scheme for companies in an attempt to avoid a slowdown

In the UK and Europe, central banks are taking increasingly desperate steps to revive their slow-growing economies. It used to be that when central banks wanted to boost growth they had to play the long game: they cut interest rates so that the yield on safe government bonds fell, prompting banks and other investors to buy riskier assets, such as company debt, making it cheaper for companies to borrow, giving them more money to spend on new equipment, offices, hiring and the like.

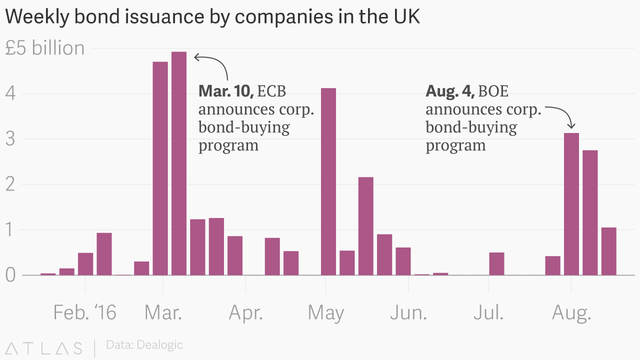

Now, the Bank of England and European Central bank are cutting out the middlemen and buying bonds directly from companies, essentially showering them with cheap cash. Unsurprisingly, companies have responded with delight, issuing far more debt than before now that they have a guaranteed buyer with deep pockets willing to pay above-market prices.

Bond issuance by companies in the UK so far this month is already £4.2 billion ($5.6 billion), compared with £3.6 billion for the whole of July. The Bank of England announced its corporate bond-buying plan on Aug. 4, as part of a package of stimulus measures unveiled to shield the British economy from the potential negative effects of the Brexit vote.

The ECB announced its new plan to buy corporate bonds in March, and over the subsequent three months companies responded with €114 billion ($129 billion) of issuance, €15 billion more than during the same period a year before. (The ECB actually began buying the bonds in June, while the Bank of England’s purchases won’t start until mid-September.)

Central banks hope that companies will use the influx of cheap cash to boost investment. And the cash is certainly cheap. German carmaker BMW has seen trading in some of its outstanding bonds push yields below zero in secondary markets. Earlier this month, it issued a two-year bond earlier this month with a yield of -0.12%. (Yes, with a minus sign.) That means if the bonds are held to maturity the buyer will get back less money than they paid in principal. The ECB is a known buyer of BMW bonds.

Meanwhile, General Electric has seen the price on its sterling bonds soar to double their initial face value (paywall), pushing the yield down from more than 10% in 2009 to a low of 1.8%. A quarter of investment-grade euro corporate bonds now have negative yields, according to Tradeweb.

On the face of it, the stimulus plan is working—corporate borrowing costs are falling and debt issuance is rising. But it remains to be seen whether companies will spend the money in ways that boost economic growth or instead use it buy back shares, pay it out in dividends, or simply hoard the cash.

There are also concerns about how the long-term effects of central banks interfering so directly in the markets. The ECB has started buying bonds in deals tailor-made for them by companies, in so-called private placements (paywall). In these deals, the debt is sold to a tight circle of pre-selected buyers instead of being offered on the open market in an auction process.

This is just the latest example of how monetary policy has become increasingly unconventional and aggressive since the global financial crisis. Printing money to buy bonds (known as quantitative easing) has become routine, and a handful of major central banks have cut their benchmark interest rates below zero. But economic growth is not exactly soaring and the returns for investors, namely pension funds, have been hammered by low rates.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance