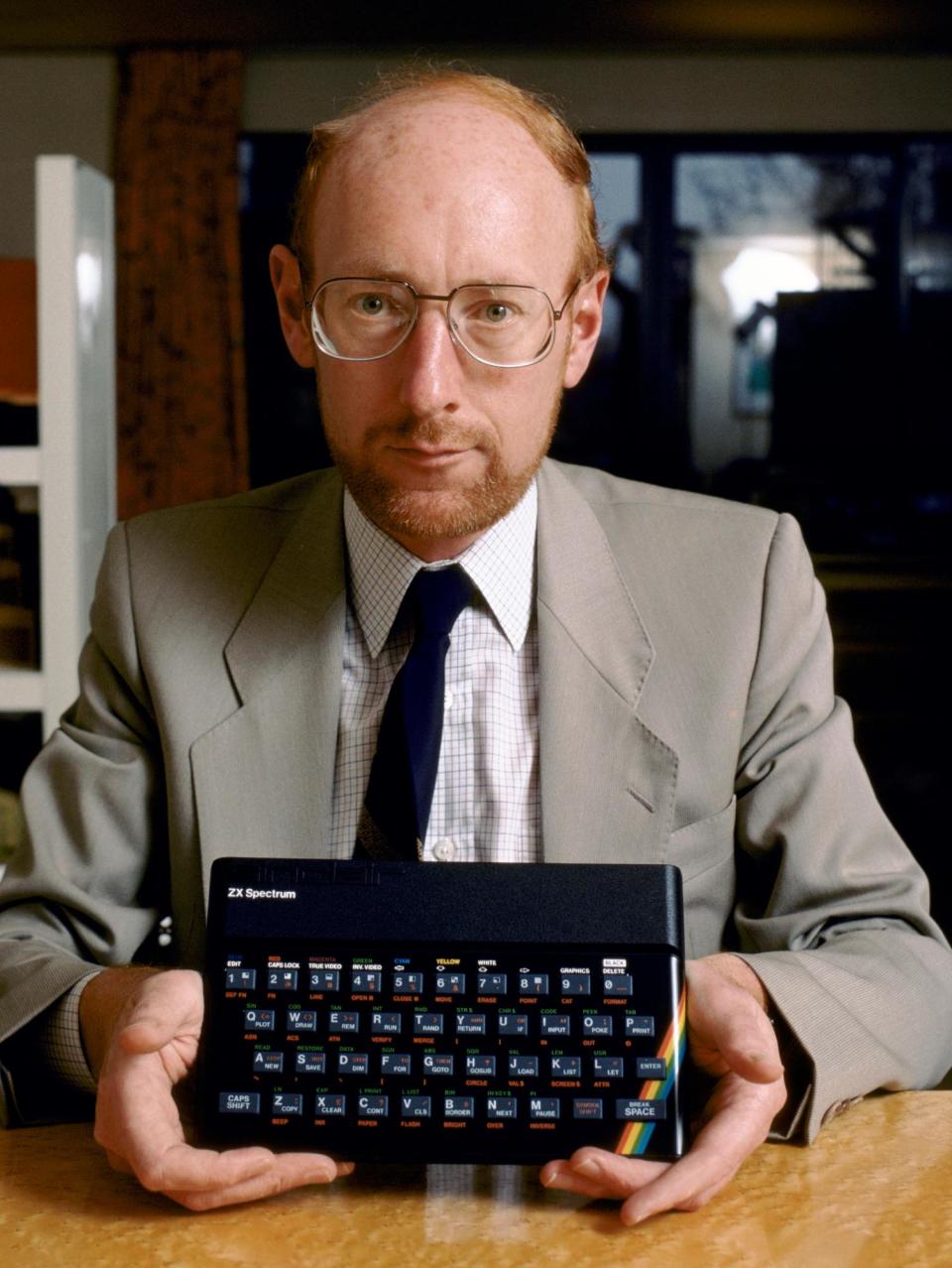

Clive Sinclair and the offbeat brilliance of the ZX Spectrum

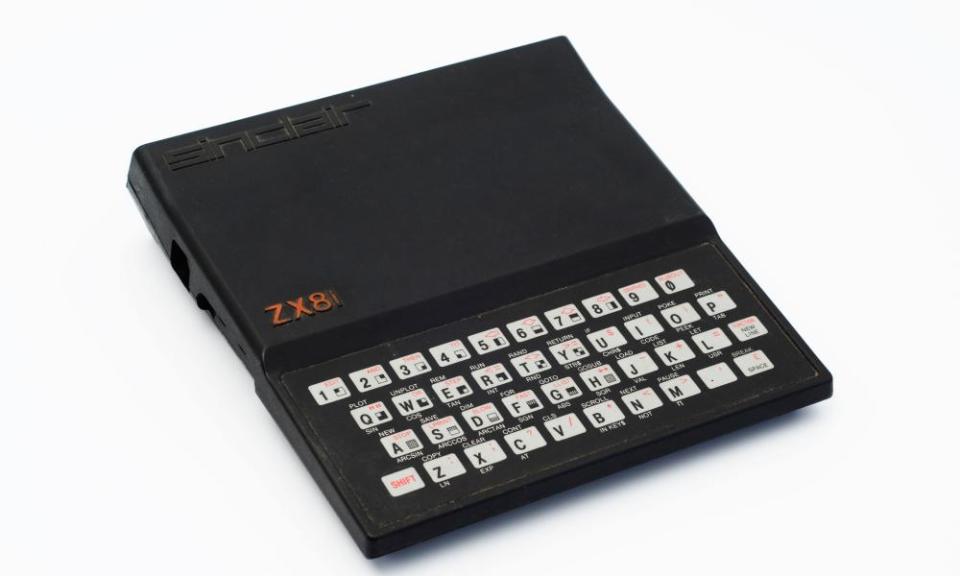

One day, in the bitterly cold autumn of 1981, my dad brought something home with him which he said was a sort of present for the whole family. It was a ZX81 home computer. I’d seen them advertised on TV and in comics but I never imagined we’d own one; we didn’t even have a video recorder. I remember seeing the instruction manual for the first time, with its beautiful illustration of a gigantic starship, and I understood straightaway that the thing my dad was at that moment plugging into the TV was the future. My whole family sat around the screen and took it in turns to type in one of the BASIC program listings from that weighty booklet. The result was a game in which you had to input coordinates to throw a ball into a waste-paper basket. I can’t even begin to describe how exciting that was. There was something on the TV that we’d made, and that we could interact with. It was a revelation.

For families all over Britain, Clive Sinclair – who has died aged 81 – brought computers home. The hobbyist computer market, which introduced the likes of Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak to programming, was not as well-developed in this country and required some engineering expertise – you built computers such as the Altair 8800 yourself. The ZX81, you could buy in Boots or WH Smiths or from the Argos catalogue, and it was all there for you. For £70. A lot of money for my family at the time, but not too much.

Photograph: PhotoDreams/Alamy

When the ZX Spectrum arrived a year later, with its colour visuals and tinny audio, it was truly the beginning of the British games industry. Again, it was more affordable than the competition – the BBC Micro, Commodore VIC-20 or Apple II – so teenagers could be given them for Christmas, and could begin making their own games on the rubbery keyboard.

There was something slightly strange about this computer. To use the memory efficiently, each sprite (or moving character on screen) was stored separately from the pixel bitmap, and overlaid on top. The process meant that colours would often leak between objects on screen – a phenomenon known as attribute clash. But just like in other areas of culture, what looks like a technical failing actually became a signature aesthetic element of the games. They looked weird and offbeat and sketchy.

This appealed to the kids making games at the time; kids brought up on Monty Python and Pink Floyd, punk and The Young Ones. Games such as Jet Set Willy and Skool Daze were slightly anarchic, miniature alternative comedy sitcoms.They drew on what it meant to be an adolescent in the 80s, with its recession and unrest. The Darling Brothers, the Oliver Twins, Matthew Smith … they were the technological equivalent of the bedroom indie pop stars of the era, and the Spectrum was their secondhand Telecaster, their Roland 808 drum machine.

I owned a Commodore 64 but my cooler friends had Spectrums. When we played together they dug out strange games I’d never seen – Atic Atac, Travel With Trashman, Fat Worm Blows a Sparky – and these experiences were as important to me as the first time I heard Afrika Bambaataa or Madonna, or the first time I saw Blade Runner on a knackered videotape. Those games came to us because of the affordable and unorthodox Spectrum, and the culture of bedroom game development it fostered.

Later, while at university, I did some summer work for Codemasters, the software studio set up by brothers Richard and David Darling with the intention of selling cheap, fun game cassettes for a couple of quid each. This was where classics such as Dizzy and BMX Simulator were born. I worked with a team named Big Red Software which handled various projects for Codies, including two Spectrum games in the winter of the machine’s life: CJ’s Elephant Antics and Wild West Seymour. Here, I worked with two brilliant programmers, Fred Williams and my lifelong friend Jon Cartwright. I got to see how clever this machine was, how adaptable, and how much joy there was still to be found in wrestling images from its ageing hardware.

“The first time I coded a Spectrum was when I blagged my way into a summer job at Big Red,” recalls Jon. “I ended up writing Dizzy: Prince of the Yolkfolk. I enjoyed coding on the Spectrum. It didn’t have the hardware sprites of the Commodore 64, and of course it had all the attribute issues of only allowing you to have two colours in each 8x8 pixel region. But honestly, those limitations drove the design of the best games.

“Shahid Kamal Ahmad’s recent Twitter thread about porting Jet Set Willy to Commodore 64 covers that well. If Jet Set Willy had been born on the C64 it would have looked and sounded so different. There were artists that specialised in doing loading screens for Speccy games. Given its limitations, it really was quite a skill. There was an anticipation too, as the screen slowly loaded in, line by line, often in black and white, almost unintelligible until finally the attributes for each 8x8 block were coloured in and it all made sense.”

Related: The 15 greatest video games of the 80s – ranked!

Even now, whenever I write about games for the Guardian, the classic titles that get readers chatting most fondly in the comments sections are Spectrum games. Jet Set Willy. Horace Goes Skiing. Knight Lore. For my generation, they retain a hold on the collective imagination and on our sense of 80s popular culture. To us, the bedroom coders that Clive Sinclair facilitated were like poets and comedians and rock stars, and they did what all struggling artists do: they made use of a tool that was affordable, expressive and open to manipulation and accident. Sinclair was as much our Brian Eno as he was our Bill Gates – he made game designers and artists and electronic musicians of so many people. I hope he realised that. I hope he knew.

Sadly our old ZX81 is long gone, though I kept it for many years. I wish I still had it. I guess everything I’ve done in my life as a professional writer started that day my dad brought that funny-looking computer home, and with it, the future.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance