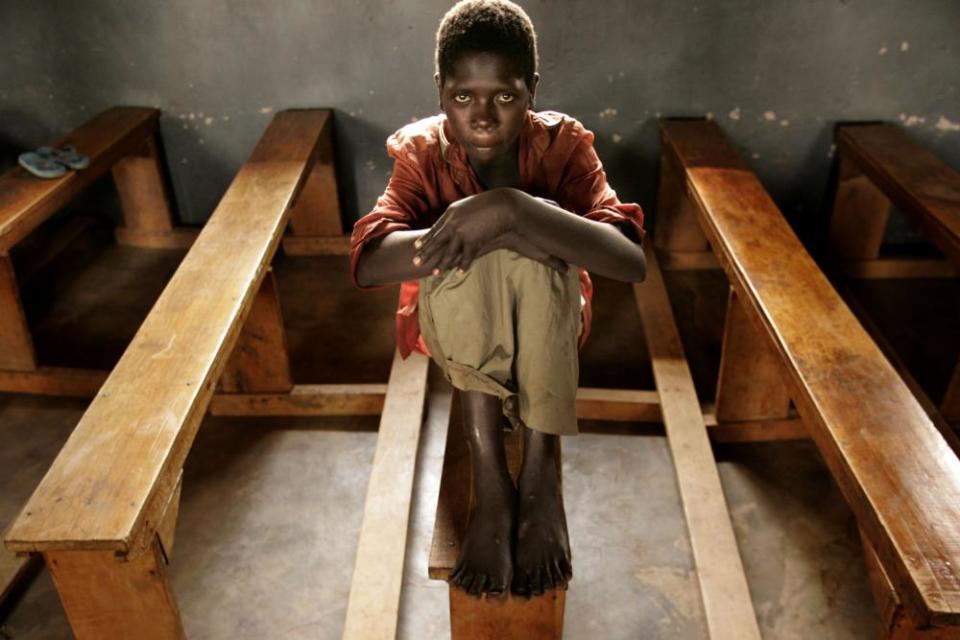

‘Collective strength’: the LRA captive restoring dignity to survivors in Uganda

When Victoria Nyanjura was abducted from her Catholic boarding school in northern Uganda by members of the Lord’s Resistance Army, she prayed to God asking to die.

She was 14 when she was taken, along with 29 others, in the middle of the night. During the next eight years in captivity she was subjected to beatings, starvation, rape and other horrors that she cannot talk about even 18 years later. Five of the girls who were taken prisoner with her died, and Nyanjura gave birth to two children.

“It really pains me that at the age of 14 I left home where not even one man had tried talking to me in terms of relationships and then to be captured and sexually exploited against my will … I really wanted to die,” she says. “I prayed for death but if it’s not your time, it’s not your time.”

Little did she know in those darkest of years, when each morning she would wake not knowing if she would survive the day and when she would see bodies discarded under the trees, that she would not only live, but become a powerful advocate for women’s rights.

After a dramatic escape one rainy night, Nyanjura was able to return to her family with her children, go back into education and start the process of healing. Previously, she had dreamed of becoming an engineer but she changed direction and instead studied development and global affairs. Her aim was to go back to her community and “do something”.

‘I need to tell the story of change’

Victoria Nyanjura

Now, her work has helped push through a major law reform in Uganda. She coordinated the Women’s Advocacy Network, made up of more than 900 women who were also survivors of the war in northern Uganda. Together they launched a petition in 2014 asking the Ugandan parliament to address the challenges they faced as they tried to rebuild their lives.

Women were suffering ill-health brought about by years of trauma. Some had contracted HIV/Aids, and many had borne children out of rape. Many survivors were stigmatised and some were rejected by families and communities who were not ready to accept children fathered by rebels. The women had missed out on education and so found it hard to support themselves financially.

The petition asked for free healthcare and better access to services, funding to support children born in captivity, training for teachers on how to work with trauma and a review of laws that require information on paternity, among other things.

Officials listened to their accounts and demands for change, and in 2019 the government passed a transitional justice policy to remedy the plight of survivors.

“I am grateful they showed us the willingness,” says Nyanjura. “[It’s as if they said] ‘We understand you exist [and] your plight, and something can be done.’”

She adds: “Through our network, I have begun to understand what collective strength truly means: survivors, community and government officials all working together towards the common goal of restoring the dignity of those who have been victims of great injustices.”

She is determined to use survivors’ voices to instigate more change at the grassroots, national and international levels. In 2018 she founded Women in Action for Women, an organisation that focuses on the livelihoods of women. After returning in August last year from the US where she studied for a master’s degree, she says: “The time has come to reach out to women and the world, to let people know who we are and what we can contribute.”

The deterioration in women’s rights since the pandemic began is a major cause for concern, says Nyanjura, adding that she has heard desperate stories of violence from women in northern Uganda, where she lives.

Many women who were informal workers lost their income and had to rely on partners and relatives. Women left their husbands, children dropped out of school, and girls became pregnant and had to embark on a different path to the one they had planned. She knows of seven women who died on the way to hospital because they could not get transport and had to walk; three of them were pregnant.

The future is now very uncertain. “These people were already struggling and the pandemic made them lose what little they had,” she says. “In northern Uganda, two-thirds of women will experience domestic violence in their lifetime. This arose from what happened during the war. Unless there is a new strategy for addressing these challenges, it will never end.”

Related: Ugandan ex-child soldier guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity

But Nyanjura is determined to contribute, and to involve other survivors of abuse in helping. It’s her way of keeping moving. “I need to tell the story of change,” she says. “I want to make people smile, and use my voice to see global change in stopping violence.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance