Should Corporate Zombies Give You Nightmares?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s something of a zombie apocalypse happening in the U.S. corporate bond market.

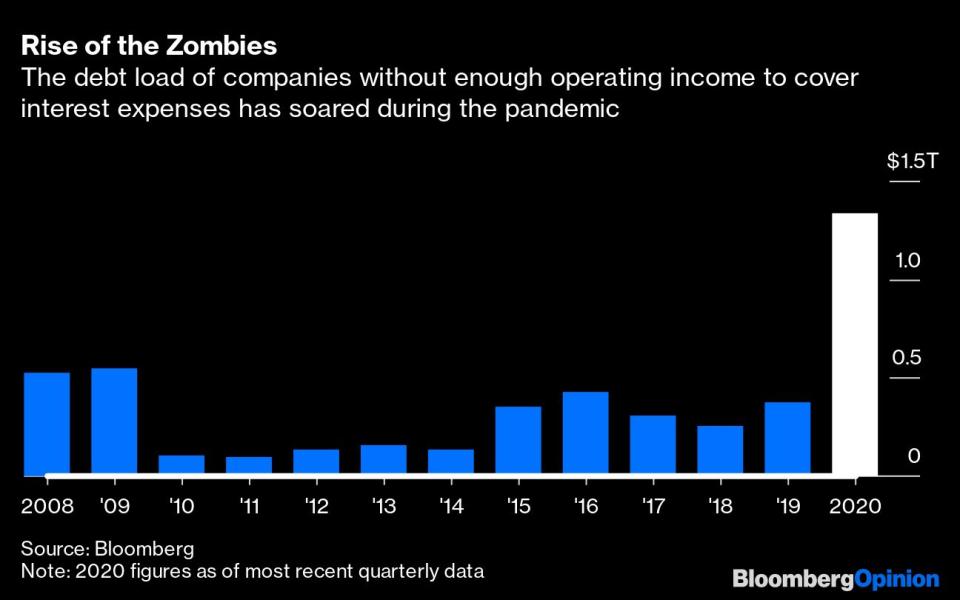

An analysis from Lisa Lee and Tom Contiliano of Bloomberg News found that 527 of the companies in the Russell 3000 index of large U.S. corporations, with a combined $1.36 trillion of debt, are “zombies” — meaning they had trailing 12-month operating income that fell short of the interest expenses they owed over the same period. That’s up from 335 firms with $378 billion of debt at the end of last year. It’s a staggering increase for a list that includes companies ranging from Boeing Co. to Uber Technologies Inc. and even vaccine wunderkind Moderna Inc., and it raises serious questions about what America’s post-pandemic recovery might look like. After all, companies that don’t even make enough to cover their obligations aren’t in much of a position to hire more workers or invest in opportunities to grow their businesses.

In starting to unpack this list, it becomes clear that share prices are only so useful as a guide. Uber reached an all-time high this week; AMC Enterainment Holdings Inc. nearly set a record low on Nov. 2. Credit ratings also can’t tell the whole story. Boeing and General Electric Co. have had issues with their balance sheets for years but were given plenty of time to sort it out and still hold investment grades. Meanwhile, Carnival Corp.’s senior unsecured debt rating was cut five separate times by Moody’s Investors Service since the start of the pandemic: from A3 to Baa1 on March 11; to Baa3 on March 31; to Ba1 on May 18; to Ba2 on June 23; and to B2 on Aug. 24. Debt from Six Flags Entertainment Corp. has an even lower rating, B3, but that’s the same as roughly 20 years ago.

Even published research on corporate zombies is mixed. On one end, there’s the Bank for International Settlements, which found that once a company becomes a zombie, its “performance remains significantly poorer than that of non-zombie firms” and it “faces a significantly higher probability of exiting the market through bankruptcy or takeover.” Yet the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggests that in an economy like the current one, zombies are worth fighting for: “It costs creditors little to keep loss-making firms in operation in hopes of renewed profitability when the economy recovers. There is nothing wrong with this outcome.”

JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon seemed to echo the latter point in remarks this week about the optics of government bailouts. “I wouldn’t not do the right thing because you might be helping a few zombie companies,” he said at The New York Times DealBook Online Summit. “Who is going to sit down and say, ‘Well these won’t survive, and these will?’ We don't have the time to do that. Get through the problem — don’t make it worse.”

It’s a lot to sift through. Fortunately, Bloomberg Opinion has columnists who are intimately aware of trends within each of these industries. Here are their views on this year’s rise of the corporate zombies.

Fright night at zombie movie theaters: AMC, the largest cinema operator in the U.S. and Europe, could soon run out of cash needed to keep the company solvent, and it can’t entirely blame Covid-19 for that. AMC and its peers responded to worsening box-office trends in recent years by loading up on debt to make acquisitions in the U.S. and internationally, install more luxurious seating, buy back stock and pay out hefty dividends. Now the industry as a whole faces an existential question. Surveys show that surging virus cases keep delaying when movie fans will be comfortable returning. In the meantime, entertainment giants such as Walt Disney Co. have made it no secret that they’re prioritizing streaming. AT&T Inc.’s Warner Bros. is even debuting “Wonder Woman 1984” on its $15-a-month HBO Max app on Christmas, the same day it gets released in theaters. — Tara Lachapelle

Not really dead. One of the biggest beneficiaries of the streaming trend is Roku Inc. — a zombie, yes, but also the most popular connected-TV device. Lower advertiser spending at the height of the coronavirus crisis did hurt the company, but Roku is less of a true zombie than a small fry in a land of giants. It joins other companies that technically qualify as zombies but are mainly growth plays like Beyond Meat Inc., Spotify Technology SA, Uber and Moderna. — Tara Lachapelle

Longing for live action. While theater-wary consumers are just as uncomfortable going to amusement parks or concerts, those businesses seem more likely to rebound once vaccines are widely available and the virus threat diminishes. Shares of ticket seller Live Nation Entertainment Inc. tripled from 2016 through 2019 before necessary pandemic lockdowns obliterated its revenue growth and made it a zombie. Comcast Corp. CEO Brian Roberts said last month that he’s “very bullish” on theme parks (it owns Universal Studios), and Disney CEO Bob Chapek signaled confidence that demand will rebound. That may bode well for other adventure destinations such as SeaWorld Entertainment Inc. and Six Flags, though it may take time before long lines form again. Cruise lines Carnival and Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. could be in a similar boat. — Tara Lachapelle

Escape from Zombieland? GE has been limping along under a mountain of debt for years. The last time the company’s annual operating income exceeded its interest expenses was in 2016 — the year before longtime CEO Jeff Immelt stepped down and it became clear GE had been aggressively chasing revenue in an oversupplied gas turbine market and splurging billions on buybacks and dividends it couldn’t afford. Immelt’s successors — first, John Flannery, and now, Larry Culp — have sold billions in assets, including GE’s rail business and its biopharmaceutical arm, to help reduce debt. Through it all, ratings companies have been extraordinarily patient. While both Moody’s and S&P Global Ratings have downgraded GE multiple times since 2016, they continue to view it as an investment-grade company even as many financial metrics have pointed to the contrary. It’s unlikely that they would break with that pattern now, especially because Culp’s turnaround efforts are starting to gain traction. Long term, however, GE’s balance sheet stress puts it at a disadvantage. The company operates in capital-intensive industries with high technological competition and its main rivals aren’t as encumbered by debt. — Brooke Sutherland

Clipped wings at Boeing. The Federal Reserve's bond-buying program opened the credit markets enough for Boeing to launch a jumbo $25 billion debt sale in April. The offering included a provision that promised to increase interest payments with each downgrade into junk, a sign that both bond traders and the company saw a reasonable possibility that Boeing might slip to speculative grade. But however dire Boeing’s finances might look and however ill-advised its strategic decisions may be, the company plays a central role in U.S. national security and is a symbol of the country’s manufacturing might. The federal government would never allow it to go under, so it’s a reasonable bet for bondholders that they will eventually get repaid. The government backstop has its limits, though, and Boeing’s future looks far from rosy. While its 737 Max jet finally won approval to fly again, appetite among airlines for deliveries in the middle of a pandemic is low, and it will take years for Boeing to unwind a stockpile of 450 jets. Free cash flow probably won’t turn positive until 2022. Boeing has said paying down debt will be a top priority once it starts generating cash again. That’s as it should be but leaves little to spend on improving its competitive position relative to top rival Airbus SE. — Brooke Sutherland

Zombies at 30,000 feet. Pre-pandemic, all of the major U.S. airlines were generating enough operating income to cover their interest expenses. Now they’re all zombies after taking on billions in new debt to cope with a dramatic slump in air travel that’s left them bleeding cash. As travel starts to return, that dynamic should reverse. It may take years, though: the International Air Transport Association doesn’t expect global passenger traffic to recover to last year’s levels until 2024. With some business travel likely gone forever as corporations adapt to virtual interactions, positive vaccine news only helps so much. A combination of government bailouts, the Fed’s bond-buying binge and creative debt maneuvers have helped give the carriers a temporary financial cushion. But additional stimulus spending would give airlines more breathing room. Most airline executives are expecting mergers between international operators, but “if the crisis persists through 2021 and dips its tail into 2022, maybe you'll even see some consolidation domestically, certainly among the second and third-tier airlines in the U.S.,” Mike Leskinen, vice president of corporate development and investor relations at United Airlines Holdings Inc., said at a Bernstein conference this week. — Brooke Sutherland

Zombies at Olive Garden. Darden Restaurants Inc., corporate parent of Olive Garden and other restaurant chains, is a zombie now but there’s a good chance it will shed its undead status once the public health crisis wanes. Business was solid before the pandemic snapped a streak of comparable sales growth that went back to fiscal 2015. Local capacity restrictions on restaurant seating will choke its sales growth for as long as they are in place. But the company is finding ways to save by simplifying menus and pulling back on marketing while improving digital capabilities to make takeout orders more seamless. CEO Gene Lee has said that his team believes some takeout orders are being generated at restaurants today by people who show up and can’t get in because the wait is too long. That’s a good sign diners are eager to return to the mecca of unlimited breadsticks as soon as it is safe to do so. — Sarah Halzack

Zombie Fashion Flops. Macy’s Inc. and Gap Inc. came into the pandemic on unsteady footing, with consumers fleeing them in favor of off-price chains, fast-fashion retailers and e-commerce rivals. The pandemic has dealt a particularly tough blow to the apparel sector, with demand for new outfits hurt by stay-at-home living. Macy’s still owns plenty of real estate that it could theoretically monetize to pay down debt. Both retailers have committed to closing a broad swath of stores in the next several years, which should help reduce costs. But these chains have fallen into sales holes this year, and it will be extremely difficult to recover. Gap’s sales in fiscal 2020 may be the lowest in two decades, according to estimates compiled by Bloomberg. Macy’s revenue could be the lowest since 2004 – before Federated Department Stores acquired May Department Stores and made the company that is now called Macy’s a much larger entity. Given their already-tenuous grip on shoppers, I suspect Gap and Macy’s will have a harder time winning back customers than some of their apparel industry peers. That’s a scary prospect, even for zombies. — Sarah Halzack

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance