Daddy longlegs: there is one piece of information every child will know

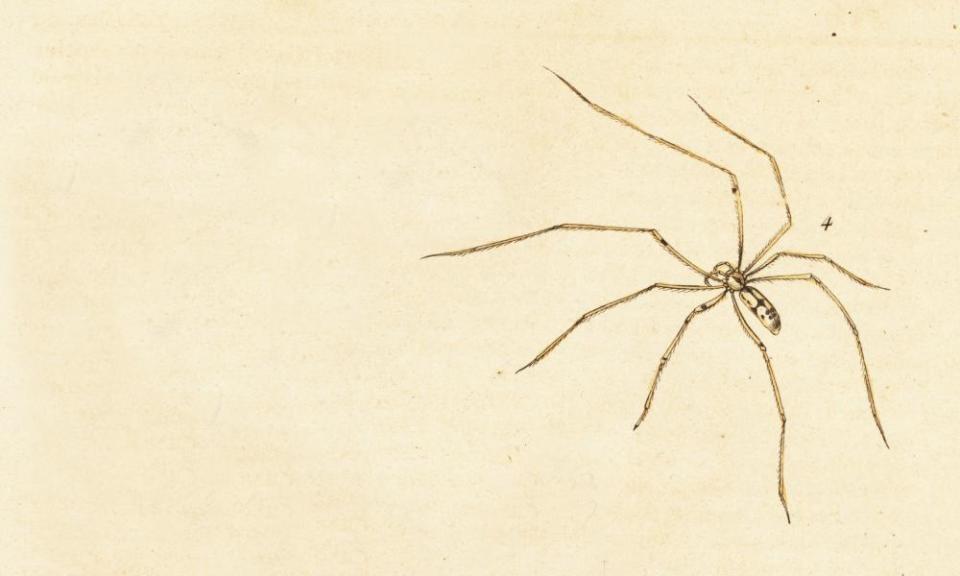

The daddy longlegs spider looks as though it was drawn very quickly on a sheet of paper by the hand of God (the hand of God is the MC Escher drawing of the hands drawing themselves) and then – perhaps after that sheet of paper was photocopied a few billion times, warming each spider up a bit – sprang off the page and into at least two corners in every home in Europe, Africa, North America, Asia, Oceania and South America – but not Antarctica, because they don’t like the cold.

Googling the daddy longlegs is a mistake, because this creature you never get too close to, and which looks pleasantly enough like a semicolon on eight spindly legs, is suddenly magnified. Now it looks like (don’t click – don’t do it!) a pitch pipe mated with a lobster.

Related: Komodo dragons: 'the biggest, worst lizard of the modern day' | Helen Sullivan

There was a tree at my preschool that in spring would grow big buds covered in soft down. My friends and I picked them, and kept one each in a matchbox, believing it would grow into a small animal.

We were idiots. Seeing this behaviour and perhaps wanting to take advantage of our gullibility – or to protect us from the harm we might easily come to – older children told us a secret: “The daddy longlegs (deep breath) is the most poisonous spider on Earth.”

As we sat on the wall at lunch, eating Marie biscuits and drinking orange squash, we passed it on. Those of us with younger siblings told them, too, to see their eyes grow large.

Maybe we let the listener sit with this information for a few hours before adding: “But it can’t kill you, because its fangs are too small”. And so all of the children in the world came to know a single piece of information.

Is it a myth? Yes, it is a myth. The daddy longlegs is not harmful to humans, but they can kill redback spiders (Australian black widows). Because redback venom can kill humans, people may have believed daddy longlegs could kill us, too.

Unfortunately, as the story was being passed on around the world, the telephone broke. There are British people and Americans who understand something different by daddy longlegs. I have been reliably informed that some of you think these are harvestmen or crane flies. It is my sad duty to tell you that you are mistaken. There is one daddy longlegs and it is looking at you right now from the corner you forgot to dust.

A reader wrote to me recently about a different house spider. It is the size of a large coin and lives in the corner above their shower.

“What’s interesting about this lady is she zooms back into the little hole when the hinged door of the shower opens with a wobble but as soon as I’m under the warm water in all my glory – out she pops,” he said.

When I was young, we had a huge rain spider living in our bathroom. It would appear for long periods of time, then reappear months later. We named it Fright and could recognise it because it had at some stage walked through white paint.

The big ones come and go, and we keep a nervous eye on them. But the company of daddy longlegs is a constant. They ask little, they stick to their corner. Sometimes they sway side to side like a basketball player, or, like an elastic-legged netball player, move their bodies in circles while their legs stay put.

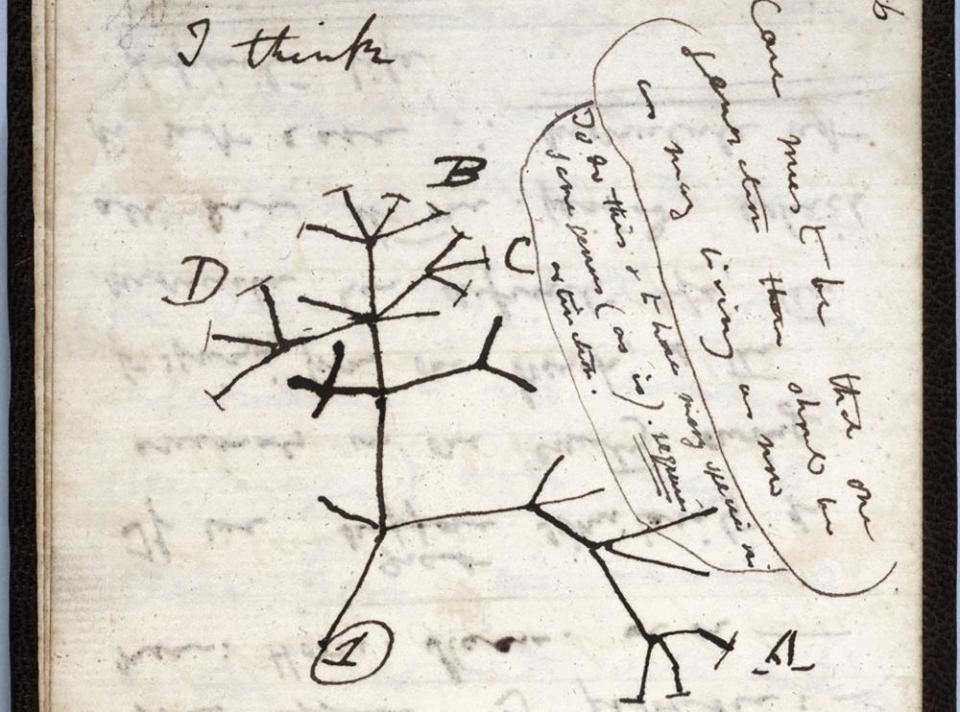

A simple gift and – whether spiders or harvestmen or crane flies – a reminder of childhood. Like Darwin’s tree of life – his early, spindly, starburst-like drawings showing his theory of evolution.

“The limbs divided into great branches, and these into lesser and lesser branches,” he wrote. Those branches “were themselves once, when the tree was small, budding twigs.”

“The Nature of … ” is a column by Helen Sullivan dedicated to interesting animals, insects, plants and natural phenomena. Is there an intriguing creature or particularly lively plant you think would delight our readers? Let us know on Twitter @helenrsullivan or via email: helen.sullivan@theguardian.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance