Daughters of the Mangrove Nine: ‘That passion in our parents was instilled in us’

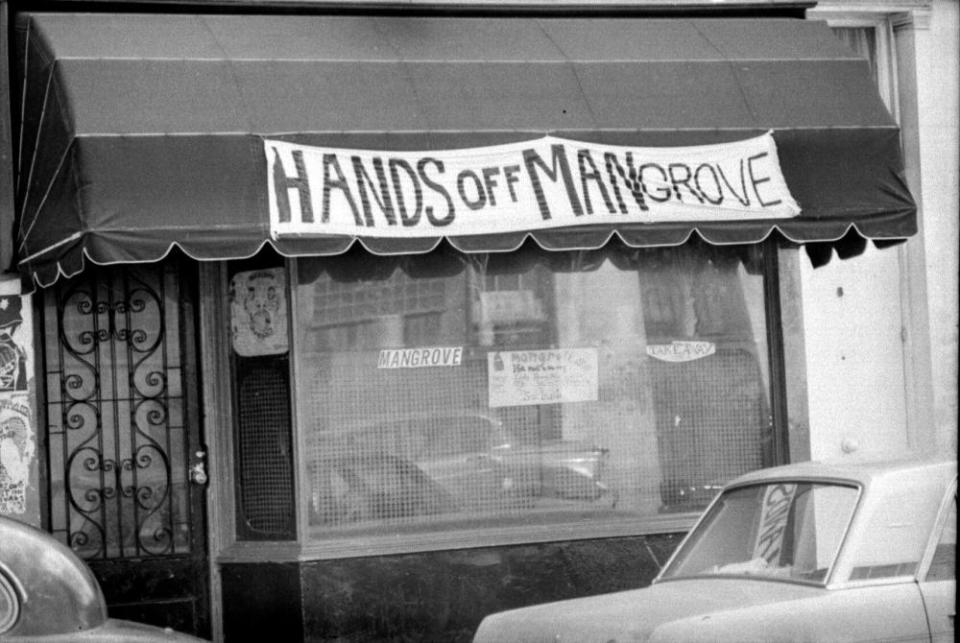

Fifty years ago next month – on 16 December 1971 – long before Black Lives Matter, taking the knee and the Windrush scandal, a group of black activists made headlines after a ruling at the Old Bailey, the court that hears only the most serious of cases. Dubbed the “Mangrove Nine”, seven men and two women had been on trial there for weeks, arrested during a protest that started outside a Caribbean restaurant called the Mangrove on All Saints Road, in the heart of Notting Hill, west London. After 55 days, the nine were finally acquitted of the most egregious of the charges brought against them – incitement to riot.

It was a magnificent victory in a case thought by many to have been politically motivated. Two of the defendants, Darcus Howe and Altheia Jones-Lecointe, decided to represent themselves (another, Rhodan Gordon, sacked his lawyer five days in to the trial and did the same) and the judge surprised and dismayed the establishment of the day by referring to “racial hatred on both sides” in his summing up.

A landmark case, then, mostly forgotten about outside west London, until film-maker Steve McQueen made his film about it, Mangrove, for his 2020 Small Axe series of dramas about key events in black British lives. Nowadays, the Mangrove Nine are no longer just local heroes; they are covered in the national curriculum and have come to wider attention in a new age of black activism and protest. As Jamaican poet and activist Linton Kwesi Johnson remarks in recent BBC documentary Black Power: A British Story of Resistance: “I think the youngsters of the BLM movement need to apprise themselves of what has gone before, so that they can draw some lessons from the battles we have fought and won.”

If I see an injustice that needs to be shouted about, I shout

Yinka Inniss Charles

It’s fair to say that Yinka Inniss Charles draws lessons from that time, as does Jamila Bolton-Gordon. Both women grew up in Notting Hill (as did I – Yinka has long been a family friend). Like a lot of people from that area, they are fiercely proud of their roots, and are active in campaigning and protesting against ongoing injustice and inequality. Their fathers, Elton Anthony Carlisle Inniss and Rhodan Gordon, were both members of the Mangrove Nine, and the women’s friendship and outlook on life have been shaped by their dads’ experiences. The march their fathers went on back in August 1970, when they were arrested, sought to draw attention to the repeated and aggressive raids on the Mangrove restaurant; raids carried out for no other reason than, according to one person interviewed in Black Power, “policing the Mangrove out of business”. Johnson says: “It was clear to the black youth of my generation that the Metropolitan police had declared war on us.” The area has, over the years, been a hostile and sometimes violent environment for black people.

Yinka remembers something of the effect on her father of living there. He was a mostly “mellow, chilled” man, but in later life he would sometimes be triggered, “angry and upset, caught up in unhappy memories, reliving the trauma he suffered as a young man on the streets of west London”. He came to this country from Trinidad as a teenager. Like a lot of West Indian families, his parents believed he would get a better education here.

Jamila’s father, Rhodan Gordon, came from Grenada in 1960 when he was 22, and would make quite an impact on his new home. “He spent a number of years finding himself, doing different things, hands in different pies, then later on he got more political,” Jamila says.

Both women are understandably proud of their fathers. For the children of the Mangrove Nine, the events of that time have a long tail. They are wary of the media (unhappy about some of the coverage of the Mangrove Nine and the Grenfell tragedy, which happened in the same area and involved friends, family, people they know); but today they want to recall their fathers, share some of their memories, as a recognition of the importance of black British history.

* * *

Yinka lives in south London now, with her children. She did a degree in law and works as a benefits adviser. She was born a couple of months after the protest in 1970, and her earliest memory of her father is from when she was about two or three and the family lived off Ladbroke Grove. “It’s of these white leather boots that he bought for me. There’s a picture – I’ve got a little afro and I’m wearing them.”

Her father was born in 1947 and came from a wealthy family in Morvant, Trinidad. “There were lawyers and judges in the family. They sent the oldest of each group of kids over to London to go to school. Later he met my mum [who is from Cork in southern Ireland] at one of the clubs they used to go to.” (These included the Rio, owned by Frank Crichlow, who would later open the Mangrove.) “He was a musician and very much into African culture. That’s why I got the [Nigerian] name Yinka.”

On the day of the protest, Yinka says that her father was beaten up on the way to a police station, “in the van and then again in a cell – that happened regularly to young black guys. They wanted them to feel they couldn’t have a life, and for my dad it was even worse because he had mixed-race kids as well.

If you had a black father, he was going to be harassed and abused by the police

Yinka Inniss Charles

“The police didn’t like it if you were with a white woman. They used to terrorise my mum as well, calling her a ‘nigger lover’, all of that. They used to trail down the road after her as she pushed her pram… as children, we suffered too.”

There was, though, more safety in crowds, and the close-knit community stuck together. “Everyone was kind of friends. Going to the same clubs. My dad had been beaten up by the police before Mangrove – that was normal, and although they [the protesters] came together for the Mangrove protest, they had been coming together already, because they had had enough of young black boys being abused by police. They all used to hang around at Metro [a youth club on Lancaster Road]. They were protecting each other from the police. Trying to find a way to get away from them. Young black men who had come over to London as teenagers.”

Yinka’s parents split up eventually and in the late 70s her father returned to Trinidad. By then her stepfather was on the scene, and: “I really stopped seeing my dad for a number of years. I think he left because he had just had enough. He and the others continued to be harassed after the court case – you don’t fight and win a case in the Old Bailey and just walk away, and nothing ever happens to you again.”

As Yinka was growing up, she always asked her mum about him. “She told me he was one of the Mangrove Nine; she also said he was a session musician, a percussionist, and that made me want to be a musician too.” She had some success as a rapper and singer in the 80s and 90s, including a hit with Love City Groove in 1995.

She re-established contact with her father when she was about 16. “I got to go and see him in Trinidad a few times. He was a bit broken by all the things that had happened. He never came back. He talked about it, but I think he just felt hurt and frustrated by what had happened here. He died too young, after a fall in 2010.”

Jamila Bolton-Gordon is currently doing a master’s in environment management, having worked in property management, and lives with her children in Fulham. She was born in 1973, two years after the trial ended.

“My mum met my dad as a teenager, she came here in the 60s from Jamaica. My dad came from Grenada in 1960, when he was 22. By then, he already had a political point of view that had been awoken in him in Grenada. Mum would see him talking in Hyde Park, at Speakers’ Corner,” she says. “Dad quickly became a community activist, specialising in law, immigration, housing and education. He developed charitable and entrepreneurial businesses.” Back-a-Yard was a Caribbean restaurant in Portobello Road; later, he opened the Black People’s Information Centre – an advice centre that provided much of the Mangrove Nine’s legal support (the family lived upstairs). “The legacy he left for the area is the black youth hostel and housing association, Westway Housing Ltd, that he helped to found.”

He was a stickler for education, she recalls. “Definitely; we had a black [history] library in the office.”

Jamila didn’t have a conventional upbringing, she says, “much to my mum’s frustration. She would have liked a more ordered life. But he just wasn’t into that. He wasn’t a conventional partner. He prioritised his work.” Her parents split up when Jamila was three, though she carried on seeing her dad throughout his life, until he died in 2018. “We were devastated. It was unexpected in that he’d recovered from cancer, but it returned.”

An early memory of Rhodan dates back to 1976, to the riot that kicked off at the end of that year’s Notting Hill carnival – the annual street celebration of West Indian culture in the area.

“I was on my dad’s shoulders and I remember feeling the tension – from laughing and joking and music and everything else and standing outside the BPIC, and then feeling, you know, the discussions changing, feeling the heightened concern. I remember us walking down Portobello Road towards the bridge and then seeing this kind of anger of people coming towards us and my dad swivelling around, and then we saw the police coming.

“Somebody threw something and my dad ran back with us, into the house, shouting something to my mum. I remember hearing all these pellets and things hitting the window and doors, windows smashing, and my mum and the other women saying: ‘We’ve got to get the children out of here.’”

Yinka says she continued to live her dad’s experience in that area as she grew up. “The police were always around. That was standard.” It was because, she says, her stepfather “used to be in All Saints Road with Frank [Crichlow] a lot in the 70s and early 80s and they [the police] were watching people all the time, and if you had a nice car, they’d stop you. He managed a couple of clubs and also experienced police injustice first hand.”

She says it was normal in the late 70s and early 80s to see the police harassing black people in the street. “Arresting people for nothing. We got used to it. Living in Ladbroke Grove, particularly when I was little, I just remember having mixed emotions, because it could be an exciting and uplifting place as well. But if you had a black father, he was going to be harassed and abused by the police. Yes, there were some bad things going on in the area, but people were also trying to run legitimate businesses that were being targeted 24/7. You weren’t allowed to do business like a white person and just be left alone.”

* * *

Yinka doesn’t think of herself as an activist, but… “If that’s what you want to call it… I have led a few marches, because if I see an injustice that needs to be shouted about, I shout.” She was involved from the outset in the local campaign to help the victims of the Grenfell fire, putting together a support group with and for Grenfell mothers, called We Can Cry. Last year she helped organise a protest to support a young black man and his family, a barman who in February of 2020 was attacked in a pub in Portobello Road by a group of white men.

“The march was called Justice for El, his mother is a friend of mine. There were big white guys taunting him, punching him. The pub didn’t do much. They left him to get home on his own. A young 20-something boy out of university whose family had already been through the trauma of Grenfell.”

She says the brewery company got quite a surprise when the local community turned out in force for the protest. “I just thought our parents would be spinning in their grave if we hadn’t done something,” she says. “We didn’t realise it was going to be such a big protest. We had the whole of Ladbroke Grove outside the pub, and it ended up in the papers.”

Yinka and Jamila are impressive, motivated women. They are in the process of setting up a charity to mentor young people who live in the area. “We want people who are successful and from Ladbroke Grove originally to come back and get involved in mentoring.” They would like to write books about their fathers and are keen to collect and archive local stories and experiences. They do a podcast together called The Next Generation of the Mangrove 9 (available on YouTube) and “we’re also trying to set up a museum to honour the Mangrove Nine and other high achievers from Notting Hill”.

[Watching the Steve McQueen film] brought up emotions that I didn’t even know I had… that I had buried

Jamila Bolton-Gordon

They are also on something of a quest – to get to the bottom of unresolved issues and missing pieces of the Mangrove Nine story. “We’ve been researching,” says Yinka. “Trying to get more information about our parents from official channels.” One thing that rankles, something they feel has been overlooked, is that four of the defendants, including their fathers, were found guilty of some, albeit lesser, charges and given – unfairly as they saw it – suspended sentences, which hung over their heads afterwards. Both women would like to see their dads’ names cleared one day.

Jamila says that watching the Steve McQueen film energised them. A few caveats aside, she found the film very powerful. “Talking about it, reading about it is one thing, but to see it visually is quite another. It kind of solidified all the different stories we had heard. It was very emotional. It brought up emotions that I didn’t even know I had, if I’m honest. That I had buried… My dad was very much ‘you keep going’, ‘you keep charging on’, and I suppose that that passion in our parents was instilled in us. It helped create the characters that we are today.”

Yinka agrees: “It took Steve McQueen and 50 years for them to be recognised as heroes. They were kind of heroes to the community [already], but no one really understood the long-term significance of what they achieved.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance