David Miliband: 'Global Britain? That phrase rings hollow'

Political life is full of “sliding doors” moments, but few what-ifs are as resonant as David Miliband’s. A little more than a decade ago, for a report in the Observer, I went out on the road with him and his brother – up to Gateshead and Glasgow – as they campaigned against each other for the Labour leadership. If you’d have asked me at the end of that fortnight who would be prime minister in March 2021, I’d have given you short odds that Miliband, D, would just be entering his second term. That alternative history would have avoided not only bacon-sarnie etiquette and the Ed Stone, but also Jeremy Corbyn and Brexit. Historians will no doubt come to argue that the first decades of the 21st century in Britain were shaped by the EU referendum, but they might also pay close attention to that previous 51-49 contest when, having won every round of the election, with big majorities among Labour MPs and members, David – long the opposition politician most feared by David Cameron’s Tories – was squeezed out at the last by the affiliate votes of Len McCluskey’s Unite union, intent on revenge against Blairites.

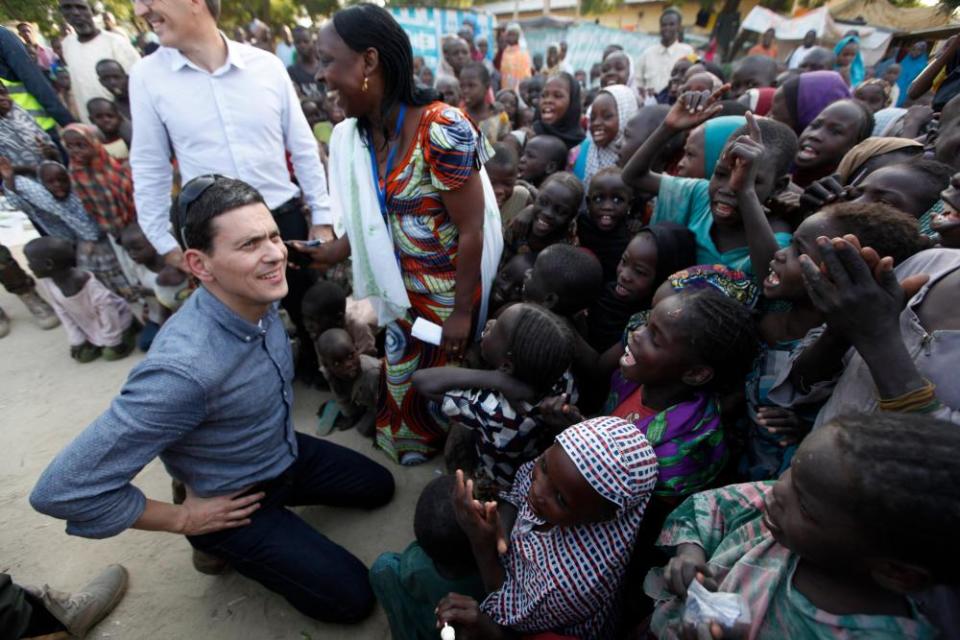

In person, Miliband, whip thin, hardly greying, has changed not much at all in that decade – on the surface at least. Grinning on my laptop screen from New York, where he has been based for the past seven years as CEO of the International Rescue Committee, the global refugee charity, he maintains the same geeky charisma – Alastair Campbell used to call him “Brains” as much for the Thunderbirds puppet as his intellect – that made him foreign secretary and Gordon Brown’s heir apparent at 42. Three years younger than Keir Starmer, the eternal centrist “king across the water” has the grown-up policy focus of the Labour leader, with an edge more wattage and wit.

The occasion for our interview is an inaugural annual lecture on the refugee crisis that Miliband is giving at the Imperial War Museum this week. I’ve been told in advance that he has no interest at all in again raking over the entrails of the past decade of Labour politics or his fraternal relations. His speech will develop the theme he has been exploring about what he calls our “age of impunity”, in which global power has become dangerously unhitched from responsibility. Watching a couple of his recent performances on YouTube in preparation, I’m reminded, nevertheless, of that “speech-that-never-was”, once leaked to the Guardian, that was to have been Miliband’s rousing victory address for 2010, in the end delivered only to his wife, Louise Shackelton, in their living room.

Last week Miliband was sitting in his wife’s study in New York. After the first grim month or so of the New York pandemic, when the family locked down in a “small farmhouse in Connecticut”, the restrictions haven’t changed much. “It’s not been Britain’s rollercoaster of different tiers and continual policy changes,” he says. “Basically, it’s wear a mask in public. My sons [now 15 and 12] wear masks at school.” None of the family have been inside anyone else’s apartment for 12 months. And obviously he hasn’t been able to come home and see his 86-year-old mother in London.

Miliband’s enormous day job, advocating and organising on behalf of that desperate, shifting “nation” of 80 million refugees – 35 million asylum seekers, 45 million internally displaced people – has clearly not been made any easier by the pandemic. When we speak, he has just come off a Zoom call with his team in Bangladesh. “I temper my enthusiasm of talk of a vaccine with a realisation that that doesn’t mean it’s going to be a factor in large parts of the world for a very long time,” he says. “So far, in the places we work, the direct health impact has been less than we feared. But the economic impact has been calamitous, and is only just beginning.”

* * *

The charity’s emergency watch list for 2021 concentrates on places where the three Cs of modern apocalypse, “conflict, climate change and Covid”, are coming together to produce what he calls “a new geography of extreme poverty”. He talks me briefly through that grim gazetteer, the who’s who of hell-on-Earth. “Yemen is a big focus obviously,” he says. “Ethiopia, we’re very concerned about because of the 4.5 million people now displaced by violence. It’s the 10th anniversary of the Syria crisis. And we try to sustain our efforts in the places that aren’t so much in the headlines – Afghanistan, northern Nigeria – not least because we know that they’ll come back into the headlines for the wrong reasons.” But the truth is, he says, as an organisation “we’ve been in a defensive crouch for four years. We are a refugee resettlement agency, we do international aid, and Donald Trump arrives, and his first pledge is to stop refugees coming into America and the second thing is to try to stop aid.”

The UK takes in seven refugees a year per constituency. No one can tell me that means they'll be ‘overrun’

Miliband’s charity, established by Albert Einstein in 1933, tried to work with the Trump administration. “But a lot of our work is about gender-based violence, women’s protection and empowerment. That became just untouchable [in the White House]. And so we’re coming out of that defensive crouch.”

He wrote a piece for CNN last month arguing that, despite all the urgency for Joe Biden to repair American democracy, international politics is not on hold, “there’s no holiday from history”. He’s heartened by the fact that Biden has pledged to take in 125,000 refugees next year (Trump had forced the number down to 15,000). He believes that Europe needs to be accommodating a collective 250,000 refugees annually by 2025. “Britain is no longer part of that, of course. But it’s wrong to say that Greece and Italy should be taking nearly the whole responsibility for dealing with refugees. At the moment, the UK takes in seven refugees a year per parliamentary constituency. No one’s going to tell me that means they are going to be ‘overrun’. And nor would they be overrun if that number was 35.”

When he sees footage of Nigel Farage in his pleasure boat policing the channel for asylum seekers in rubber dinghies, or Priti Patel talking tough about prison ships, how does he feel?

“Well, I’m long past shock,” he says. “There are spikes and troughs in compassion. And, you know, Britain’s done amazing things in welcoming people in the past, for which my family has particular grounds to be grateful. But it also has darker sides to its history. My own view is that when issues of immigration, and issues of refugees get confused, it’s neither good for immigrants nor good for refugees.”

He reminds me that his mantra in the 2010 leadership campaign was that Labour needed to stand for “empowerment, belonging and control”. He has watched on from afar as the solidarity he hoped was implied in those three words has been reframed and hardened by the right.

His recent speeches have restated the idea that it is strong, positive shared national values that have historically engendered a “duty to strangers”. When talking of this duty he references not only the example of his parents – Jewish refugees from the Nazis who were welcomed in Britain – but also his aunt and paternal grandmother who were in Brussels when war broke out. In 1942, his grandmother received a summons from the occupying Gestapo authorities to undergo “registration” at the city’s railway station. Though some relatives told her that it was dangerous not to go, she immediately packed her bags and made her way with her daughter to a village south of the city where they had spent holidays. When she arrived at the house of one of the local Catholic farmers, Monsieur Maurice, she pleaded with him to take them in. For the rest of the war, at enormous risk to himself and his family, Monsieur Maurice hid her and her daughter. As a teenager, nearly 40 years later, Miliband went with his aunt to visit Monsieur Maurice at his farm, and asked him why he had chosen to take that risk. He has never forgotten what the old man said, simply, in reply: “On doit” (one must).

Miliband talks of a generational crisis in such kindness, of the ways in which “antisocial” media and populist politics have threatened to “turn hearts to stone” when it comes to refugees. If he had to give reasons for this collective failure of the international community, he would point to the fact that humanitarian intervention was designed for war between nations not within them; and the paralysing effect of foreign policy failures in Iraq and Afghanistan. (Miliband, a junior member of the Blair cabinet that took Britain to war in 2003, has spoken of regret at that vote – it appears to be one of the reasons he chose to take up his current role. “You can’t make up for foreign policy errors by humanitarian action. But when you break something you have a duty to help repair it.”)

He argues that the response to populist impunity – “the ideological shift against liberal democracy” – has to come from strengthened institutions, what he calls the “countervailing power” of civic society. I think there was a time that he might have emphasised that such fellow feeling was rooted in fairness, that necessary sense that “we are all in it together”, but in recent years those righteous arguments against inequality have become harder for him to make.

As I point out to him, if you Google Miliband’s name, some of the first results are news stories – “million-dollar Miliband” – about his pay packet as charity CEO, which rose to a staggering $911,796 (around £741,883) in 2019 (an increase of nearly £200,000 in the previous two years, and two-and-a-half times the whopping amount enjoyed by his predecessor in the role). It seems to me and I’d guess to most people, I suggest, an extraordinary amount of money to be paid to work on behalf of the dollar-a-day poor. How does he justify it?

He likes to talk in lists, and he gives me a little list of reasons.

“I say to people,” he says, “first, it’s right that it’s public. Second, that there’s an independent process that makes these allocations. Third, that I am paid four-fifths of the average of the peer organisations in New York. And finally, I said to people, look, the financial structure of the organisation is that we’re sitting on $125m endowment that yields seven or $8m a year or has done over the past 10 years. And we make sure that our executive salaries are more than covered by the money that comes from the endowment. So anyone who is donating to us can be confident about where their money is going.”

All of that is no doubt true – benchmarking and remuneration committees have long been the fairy godmothers of the fat cat – but surely he can see that the symbolism is a problem when he’s arguing for greater global fairness. He must recognise that it gets in the way of that?

He makes the argument that the important thing to consider when thinking about executive pay in the charity sector is outcomes. The charity has doubled in size, and multiplied its measurable effect in the past seven years. “We do more studies about what really works than anyone else. So we’re hard-headed about impact. I feel we’ve got a real story to tell about how to make a difference…”

* * *

Listening back to that part of our conversation later, it sounds to me a little like a microcosm of the Blair years, that admirable focus on positive outcomes, allied to a pragmatic enthusiasm for the driving forces of capitalism (most infamously articulated by Peter Mandelson: “We are intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes”). The principal architects of New Labour and the “third way” have, you might say, walked that particular talk since leaving office, not least Blair himself. The Mephistophelean pact with the bankers and lawyers of the city of London – we’ll keep regulation light and your taxes will pay for new schools and hospitals – always had two implied philosophical underpinnings: the first, “how else do you generate wealth?”; the second, “does inequality matter if it serves the greater good?”

But if the past decade has taught us anything, it would surely be that enormous wealth inequality fundamentally does always matter. If you were looking for facts to support that belief, you might well examine the corporatisation of charity, and the damaging cynicism it fosters.

One of the great achievements of the Blair and Brown governments of which Miliband was a part was their world-leading determination to “Drop the Debt” and the commitment to spending 0.7% on foreign aid. Miliband’s remuneration for leading a hugely complex NGO over 40 countries with a £785m budget is far from unique. Still, he’s surely too smart not to see how tabloid headlines about it might have made Johnson’s government’s decision to drop that historic commitment of 0.7% a little easier.

In recent years the IRC has received around £50m in taxpayers’ money from the UK for its life-saving work. Some of that funding is now threatened. Miliband is properly alarmed by the cuts he is already seeing. “We’ve got an amazing health programme in Sierra Leone,” he says. “And it’s basically being halved. We’ve been doing critical child protection work in Lebanon, which we fear is being pulled completely. We’re getting notified by British embassies around the world of cuts to programmes.”

A couple of days after we spoke this alarming trend was compounded by Britain slashing more than half of its aid commitment to the people of Yemen. Miliband responded to this decision with anger and disbelief: “At a time when acute malnutrition among children under five in Yemen is at record levels, and when the UK has made leading global efforts to avert famine the hallmark of its aid policy… it is hard to imagine a more self-defeating decision for the UK, or disastrous decision for Yemenis. Without funding, UN and humanitarian agencies will have no choice but to scale back life-saving programming and more Yemenis will die. What we have seen today are not the actions of a “global Britain”. That phrase rings hollow… Make no mistake, as the UK abandons its commitment to 0.7%, it is simultaneously undermining its global reputation.”

Before we finish our conversation I suggest that in the past couple of years he must have generally been watching British politics with his head in his hands?

“Well, I’m always hopeful about the UK, not fearful,” he says, “but obviously the attempt to prorogue Parliament, making judges enemies of the people, all that is very antithetical to a functioning democracy. It’s still my country. And, you know, I’m obviously passionately concerned about it… As I say, the debate of this decade is going to be accountability versus impunity. And we need to be on the side of accountability.”

He doesn’t indulge in might-have-beens, at least not in public, but does he ever envisage a future back in British politics, as some still hope?

“I want to do things that really allow me to make a difference,” he says. “That’s what I tried to do in politics. And that’s what I’m trying to do now.” He smiles. “I think it would be fair to say, I was never very good at career planning…”

David Miliband is a key speaker at the Imperial War Museum Institute’s first annual lecture. The free event will be livestreamed via Crowdcast on Thursday 11 March at 5pm

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance