Does Anyone Care About the Oscars Anymore?

In mid-January, writer-director Paul Schrader asked the world of Facebook if anyone cared about the Oscars. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (can we add Flim-Flam?) had vowed on Oscar’s sword that the 13.5in figurines in bronze and gilt would be distributed with due flash and glitz on 25 April. But… how do you define flash and glitz legally so as to get past insurance liability? Who knew how the virus would vote in April?

There were problematic “ifs” and too many crossed fingers to hold the heavy icon (eight-and-a-half pounds — just over standard newborn weight). Uncertainty was everywhere. Like who would be the host? Well, keep this to yourself, but there was a big golden personality, the most riveting on-camera dude in the world, who would be available. Was that going too far, if it could tap into some 75m viewers? Or would it outrage every standard of civic decency, moral elevation and multiracial harmony (you remember those things) the Academy was pledged to?

Probably not a good choice, though the Academy was desperate to regain its numbers. In the early years of this century, the awards show could count on 40m viewers (with advertising to match). But that 2020 show had been the least popular ever with an audience of 23.6m, a 20 per cent drop from the previous year. And while Parasite was a cute and unexpected Best Picture winner, it didn’t quite encourage a “see you next year” feeling. If the Academy couldn’t get the advertising revenue from that one-night spectacular then maybe it would lose major network interest, and find its overall budget reduced. Unless Netflix came in with a lowball rescue bid. Or Prime — could they rename Oscar as Amazon?

Schrader’s question was where all Hollywood questions end up: it was on the money, and it voiced a worry that had been hanging in the air since long before the dawn of Covid. Does the great, fickle public get excited about the Oscars still? Are you as anxious over who will win best adapted screenplay as you are about Liverpool and Man City vying for the Premier League? Or when you’ll get your vaccine? As a test, can you recall who won the acting awards when the envelopes were opened in February 2020, as the lights were going out in movie theatres? (If you get three out of the four right you can keep reading.)

Many are wondering if a live TV Academy Awards show, with red carpets, uneasy hosts and gowns like peonies after rain can stand up to the reality that the largest live crowd for the inauguration of President Joe Biden was armed, in uniform, and very tense about where the terrorists would come from. Don’t we understand at last that the contests we face — the profound matters that loom over a tottering and demoralised civilisation — cannot be appeased by those precious, gold-plated voodoo dolls?

Well, you sigh, give us a break, don’t we deserve a little fun? Doesn’t lockdown qualify for a splurge of glamour and showtime in Los Angeles? Of course it does, but in January it was plain that no city in America was having a worse time with Covid. With the best will in the world or the most farfetched hopes, the red carpet parade wasn’t going to cut it. And if Joe Biden had to get his prize in eerie isolation, then why not ask the same for Frances McDormand in Nomadland, a unique study of an emotional loner in the desert hacking it on her own?

Then in casual talk, texting or on the phone, it became clear that few people had seen Nomadland, and no one regarded it as a major entertainment event like Star Wars. If I talked Best Actress to my friends, there were votes for Carey Mulligan in Promising Young Woman, for Vanessa Kirby in Pieces of a Woman, and for Rachel Brosnahan in I’m Your Woman (among several others) but no one I spoke to believed any of those fine performances came close to Anya Taylor-Joy in The Queen’s Gambit.

So how does Gambit not qualify — it wasn’t a movie, even if for several nights in a row we were thinking of little else? And we had watched it on the same screen and from the same sofa employed for all the other contenders. The Queen’s Gambit was a cultural event. It made chess into a lockdown craze. I wanted Taylor-Joy ’s character to win her game, and if she qualified then I would watch the Oscars because I’d be rooting for her.

And year by year, I fear we’re rooting less, so Oscar looks more like a stooge. It’s ridiculous that shows like The Queen’s Gambit are hived off into different awards when they are made like movies, and watched in the exaltation with which we were once absorbed in Chinatown, or Casablanca, or Some Like it Hot. In struggling with the obscure aspirations of Tenet or Mank, I had to feel that a deep problem for Oscar is the diminishing narrative grip of our movies.

Something elemental is at work in how we watch screens, and it is as significant as the way in the early 1900s everyone decided to watch the flickers and then in the late 1920s they said why bother with silence if sound exists.

No question, as and when Covid is put to rest, there will be a wild surge to get out, to mingle, to kiss strangers and do all the impromptu things we have been missing. But will the urge last? Or will the public face realise that for 20 years now, the best American movies have been made for our home screen — on regular television first and then in streaming. The quality of The Wire, Breaking Bad, Fleabag and Ozark is — in my opinion — superior to what theatres want to show us.

I’ll go a step further. Late in 2020, our local movie house in San Francisco did reopen briefly and my wife and I took the opportunity, heavily masked and ready to sit far apart. So we went to see Let Him Go, with Kevin Costner, Diane Lane and Lesley Manville. It was an enjoyable, old-fashioned thriller, not great but decent. Our care over distancing was irrelevant: there was only one other person with us in the 200-seat theatre (and he could have been a cut-out borrowed from ball games). Still, we felt good at being out, except for one thing. The new circumstances of watching made me aware of something I had been overlooking for years. The quality of picture and sound in the cinema was pretty bad. To put it another way, the experience felt less seductive or gratifying, and a lot muddier to listen to, than if we’d been watching the same movie on our home plasma.

Yes, the image was bigger, and I love that size. But brightness, or illumination, means a lot — it’s the chance of enlightenment or rapture. Plus watching it at home is a lot cheaper. That’s on the money.

For years before Covid, the audience was accommodating itself to these realities. A new passion arose. We called it “bingeing”, the zeal in discovering a new show and running through its entirety: you could do Babylon Berlin in a week — and for me that German show is the movie event of this century, with all the extra impact of a period story alerting us to a helpless slide towards fascism at a time when we had not quite identified it in our modern life. You can’t give us the kind of golden age we have been having with streamed TV without us reappraising the nature of gold.

Nor can you arrange the world as a show on TV every night (that really has been the Trump fantasia), without our realising that the essential melodrama — like the invasion of the Capitol on 6 January — is happening in our living room and running eight hours at a stretch (the dread compulsion of watching on the sixth). For years I have felt the discontent with a drab theatrical movie of wanting to get home to reconnect with the real drama on TV.

The theatrical movie kingdom has been receding for a long time, and the old citadels of Hollywood (including the Academy) are terrified of that. They clung to the Oscars as a test of faith — “Look, you still believe in us, don’t you?” The Academy moved with frantic speed to catch up on its own decades-long defects. It worked to rearrange its membership, bringing in more young people, more women, and more of what were once called “minorities”. It has about doubled its membership. But that is no more reassuring than the body of Americans who prefer vested privilege, the subordination of women and the suppression of people of colour. Against that there is the mounting feeling that, in what claims to be a mass medium, shouldn’t a popular vote determine worth? Do you see how the Oscars are a metaphor for an electoral college in conflict with the mass vote?

The Oscars were always a self-congratulatory night for a club anxious to think well of itself. But the larger community, the country, is at last coming to terms with how badly it has been doing most of its life. Thus, our landmark films may fade into obscurity or ignominy: you can’t show The Birth of a Nation now because its assumptions are so hideous and damaging. Gone with the Wind is close to the same disappearing act. How long before we recognise The Godfather as a woeful tribute to the club of male superiority and its

systemic criminality.

Cut us some slack! I hear you, and I have lived my life in the church that cherishes movies as a romance or a dream that helped us through bad times — not just depression and war but the local disappointments in our non-famous lives. So while I thought Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood was shameless wishful thinking, I was all for Brad Pitt getting the supporting Oscar in it. That’s because I like Brad and find some daft joy in his smile.

Even so, in our changed times, I doubt anyone would dream of making Thelma & Louise where a smiling Brad got to fuck Geena Davis in 1991, and Thelma was as liberated by it then as we were. We know we can’t make those movies any more — and we are in grave trouble because we made them for so long.

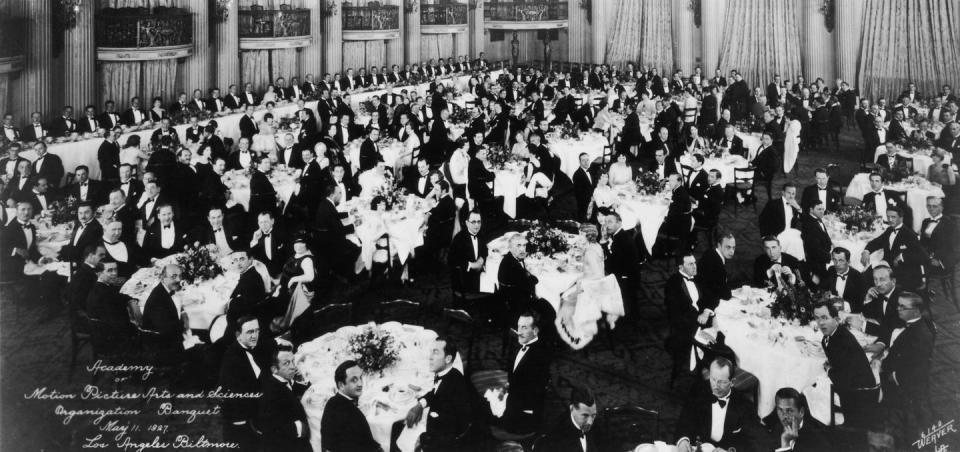

The Academy when it began was not a real academy. That lofty word was flim-flam masking for a boys’ club intended to stop unionisation in the film business, to divert the public from a series of scandals in the 1920s, and to say, “Look, aren’t we great?” Our last four years have done so much to rid us of that chant over greatness. By 25 April, as Biden faces so many problems more challenging than the mayhem in

disaster movies, we are going to have to admit that greatness had gone out of fashion. So maybe its prizes are old hat too.

I think Paul Schrader is dead-on with his question — though I bear in mind some possibility that he was also pissed because he didn’t win for First Reformed, or even get nominated for a work as great as Taxi Driver.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance