How Labour lost touch in a Leave-voting former heartland

Labour lost almost five million votes between its landslide victory in 1997 and its fall from power in 2010.

Some believe the party haemorrhaged working-class support in former strongholds like Thurrock, an industrial district along the Thames just east of London. Its share of the vote locally almost halved between 1997 and 2015.

The Conservatives now hold it with a wafer-thin majority of 345 votes, making it a hard-fought battleground this election.

“Labour lost a lot of support here when it went to ‘New Labour,’ and became watered-down Conservatives. They moved away from supporting the common person and lost credibility,” said James Woollard, who quit his job as a bus driver to run as an independent candidate in the seat, to Yahoo Finance UK.

But as Britain heads to the polls, former prime minister Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ rebrand is dead and buried.

READ MORE: Honda workers divided over Brexit as plant closure hangs over election battleground

On paper, Labour today should be a revitalised force in places like Thurrock. New leader Jeremy Corbyn has embraced a radical economic programme, and claims it would transform the lives of ordinary and hard-pressed families.

But recent opinion polls suggest the Conservatives lead Labour by 12-15% among working-class voters. Only a third of voters think Corbyn can relate to people like them.

In Thurrock, the Conservatives’ majority is predicted to skyrocket from 0.7% to 24%, turning one of Britain’s tightest marginals into another safe blue Essex seat.

The question is — why is Labour just not cutting through? Brexit looms large, but it is far from the whole story.

From Blair to Corbyn: the reinvention of Labour

Tony Blair reinvented his party in the 1990s. Labour embraced free-market economics, a more liberal agenda and political spin, widely credited with winning over more affluent floating voters and securing 13 years in power.

But disillusion is widely thought to have sunk in across former heartlands at a feeling among voters the party no longer spoke for people like them. Turnout plummeted to near-century lows by 2001, and it lost seats like Thurrock.

Since 2015, Labour has been reinvented again by the unlikely leadership of a once little-known backbench MP. Where Blair tried hard to convince voters would keep down spending, taxes, borrowing and regulation, Jeremy Corbyn is promising loudly to do the opposite.

READ MORE: Business leaders in despair over choice between Corbyn and Johnson

The days when Labour could be accused of being “watered-down Conservatives” and its leaders of being too slick or safe are long gone.

Its new leader has unveiled the most left-wing manifesto in decades, from a £10 minimum wage to banning zero-hour contracts, reviving trade unions to nationalising whole industries.

Business leaders warn the controversial agenda sends “chills through boardrooms,” and conventional wisdom suggests it risks alienating middle-class voters Labour needs to win.

But such radical politics might be expected to strike a chord at least across Labour’s old heartlands, and win over Thurrock voters like Jim Thompson.

Labour heartland in Britain’s docklands

“I’ve lived in the area all my life. My dad and his dad worked in the docks, and obviously it was Labour, Labour, Labour,” said Thompson, 61, who now cares full-time for his elderly father.

Like many locals, Thompson’s own history and politics is intimately bound up with London’s history as one of the world’s busiest port cities.

The docklands defined the lives and identities of working-class communities along the river for generations. It was through low-paid, unsecure, and often dangerous work that many dockers learnt their politics.

The Thurrock town of Tilbury was just a few rows of houses until a dock opened in 1886, to ease congestion in the East End docklands.

Housing sprung up around it as labourers flocked to find work loading and unloading ship cargo, from timber and grain to Indian chutney.

The docks were also a hotbed of activism. Tilbury dockers were involved in major strikes throughout the 20th century demanding better rights, and some helped found Britain’s trade union movement and the Labour party.

It helped make Thurrock a Labour area for more than 40 years after the seat’s creation in 1945.

Fading party loyalties as dockers lost their jobs

A technological revolution changed the area forever from the 1960s. Firms began using bigger ships stacked full of giant metal containers, using cranes instead of people to unload them.

Demand for dockworkers like Thompson’s dad collapsed. ‘Containerisation’ sealed the fate of hundreds of thousands of families reliant on dock jobs, from London to Liverpool.

Unions in Tilbury managed to block containers for two years, but the writing was on the wall.

“They offered people severance pay, so my dad took it,” Thompson explained outside his home on an estate in neighbouring town Grays. One in five men in Tilbury was reportedly on the dole by the 1980s.

Party loyalties have faded as the area’s dock heritage has faded, and now have to be earned rather than inherited. Thurrock turned Conservatives in 1987, fell to Labour again in 1992 and has been Conservative since 2010.

READ MORE: Can the Lib Dems win even in Britain’s most Remain seats?

“In days gone by I always voted Labour, but I’ve never been vehemently Labour,” said Thompson.

He described himself as “disenchanted,” and he and his partner both rolled their eyes when asked about Blair. They seem like exactly the kind of voters Labour stood a chance of re-engaging with a more radical programme.

Thompson never worked in the docks, but his own experiences at work have clearly influenced his views —and some of them sounded strikingly similar to Corbyn’s.

He lamented the rise of insecure work in Britain. “Over the decades, the things the unions built up like nice, safe conditions have slowly been eroded,” he said.

He said in his first job at a local factory as a young man, he had enjoyed the same rights on day one as workers who had been there decades. “That doesn’t happen now — you don’t get proper contracts. When I went back to do the same job a few years later, it was like I was doing the work of four people.”

The rise of insecure work in modern Britain

A crucial problem for Corbyn is that while he may have turned the page on New Labour, many voters have noticed precious little of his plan for the next chapter.

Thompson hadn’t heard any of Labour’s pledges to improve working conditions. He hadn’t heard Corbyn’s attacks on the Conservatives either for crushing trade unions and de-regulating the economy in the 1980s.

His partner Joy Day, who is on the minimum wage, hadn’t heard Labour’s promise to hike it to £10, and sounded sceptical even when she did.

The 63-year-old said she left for work at 5am each day, earning £8.21 an hour as a cleaner.

“Everything’s minimum wage. That’s no good. I could be 70 when I retire,” she said with a sigh. But she added: “They’ve been saying they’re going to put it up for a long time. It won’t be a big increase.”

Employment has hit record highs in Britain in recent years, but pay has been squeezed and precarious work has grown since the financial crisis. Labour has made countless promises to help hard-pressed workers, but breaking through a wall of disillusion appears an almighty struggle.

Few other voters interviewed in Thurrock by Yahoo Finance UK had heard any of the party’s plans beyond Brexit. Few expected any government to ever improve working conditions, despite widespread complaints about the quality of local jobs.

As in many places hit hard by industrial decline, Thurrock has seen giant warehouses and shopping centres spring up as dock jobs and factories, including the one Thompson worked for, have disappeared.

A forklift driver on his lunch break in Tilbury’s run-down town centre said he used to get night shifts for £15 an hour at a local factory two decades ago.

“An agency’s just offered me £8.60-9.50 an hour, which is ridiculous. That could be one shift, and they put wages through an umbrella company so by the time they’ve had their bit you’re thinking ‘where did that go?’,” he said.

He added that he’d “like to see everybody on a fair wage,” but never voted in elections. “They say things, but they’re not going to do f*** all, are they? Boris [Johnson] can’t even brush his hair.”

Still London’s little-known ‘gateway to the world’

Even at the modern Port of Tilbury, there were few signs of the fiery radicalism of days gone by.

Workforce numbers have markedly shrunk, but it is still a major port, an important source of jobs and an often-overlooked ‘gateway to the world’ for London.

The distant hum of lorry engines flowing in and out and the clank of containers being moved can be heard from many nearby streets. Giant cranes and ships on the waterfront still tower over Tilbury, and another port opened nearby in 2013.

Timber and grain are still transported, with cars, waste, recycled products and other goods making up the rest of the 16 million tonnes passing through the port each year.

Some port workers went on strike a few years ago over pay, but two told Yahoo Finance UK they were grateful to have jobs at all.

“A job’s better than being on the dole,” said one worker in hi-vis heading home.

Former Labour voters backing Johnson on Brexit

A seemingly bigger problem for Corbyn though is the unpopular messages which have struck home about him, rather than the potentially popular ones that haven’t.

Above all, Corbyn is simply on the wrong side of the Brexit divide for large swathes of the electorate.

The Thurrock council district had the fourth highest Leave vote in Britain, and almost everyone interviewed by Yahoo Finance UK was angered by Westminster’s failure to deliver Brexit.

It means Thompson and Day are both considering the previously unthinkable — voting Conservative.

“Brexit destroyed my faith in voting,” said Thompson. “They had a clear mandate. If Johnson sticks to what he said, it could be good for the country.”

Tony Judd, 75, a volunteer at Thurrock Yacht Club, said he felt “sick” about backing Johnson but saw little alternative.

He said: “Boris is a buffoon, but what else are you going to have if you want to get out? Round here, 72% voted out.”

Judd belongs to the Brexit party, but it has withdrawn candidates in Tory-held seats, which could prove more vital than anything else in seeing off Labour here.

Britain’s new political divide

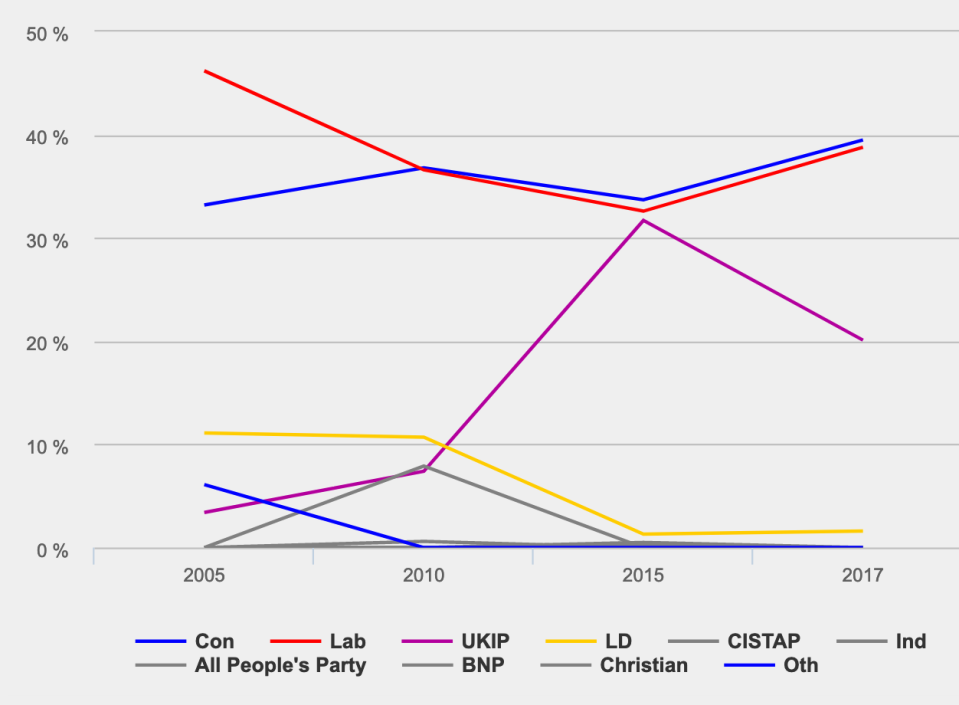

Brexit has deeper roots in Thurrock than many places. The BNP (British National Party) occasionally won council seats in the 2000s, while UKIP (UK Independence Party) gained many in the 2010s and came within a thousand votes of victory in the 2015 general election.

Liberalised immigration policies under New Labour may have been just as crucial as liberal economic policies in fuelling anger and a sense of politicians as out-of-touch in places like Thurrock.

A 2012 survey showed 59% of Labour’s lost voters backed Brexit then, and 79% wanted net immigration slashed to zero.

But Brexit is arguably a symptom rather than cause of Labour’s deeper malaise, crystalising a wider political divide. Surveys suggest Remainers are more likely to be socially liberal, Leavers socially conservative.

READ MORE: Trust sinks in politicians as Brexit chaos and election promises fuel despair

Labour may have lurched leftwards but it is arguably more liberal than under Blair, with Corbyn instinctively pro-immigration and party ranks swelled by liberal younger activists.

On issues from crime to security to the monarchy, the number of Thurrock residents slamming Corbyn and liberal politics more widely was striking.

Such issues began eroding Labour support long before the referendum or Corbyn’s rise, but he may have exacerbated the problem.

Judd said Corbyn looked an “absolute fool” in his recent interview on the Queen’s Speech, and reeled off an array of wider complaints from feminism to votes at 16 to limits on smacking children.

“He’d be had up as a traitor in the post-war years for cavorting with suspected terrorists,” exclaimed Thompson.

On the brink of another technological revolution?

Many voters defy stereotypes. Several said sovereignty and value-for-money was behind their Leave vote, not migration. Thompson said he saw himself as a “globalist” and a “person,” not someone with a particular nationality.

Labour also still has significant support, even among voters wary of Corbyn. “I don’t think Labour’s the best to carry out Brexit, but I’m swaying towards them on the NHS,” said one wavering voter.

Katie Bright, 20, a full-time carer for her disabled siblings, had researched Britain’s parties online for her first election vote. She hoped a Labour victory would tackle rising homelessness and foodbank use, and mean more help for carers.

Whatever the outcome, Thurrock could be caught up in yet another technological revolution. Amazon’s biggest European warehouse opened recently in Tilbury, where “robots and people work together” to pick, sort and move packages.

The company says its robot-staffed centres employ more staff, not fewer, and also highlighted £10.50-an-hour starting pay amid claims of gruelling working conditions.

But if a new era of automation does threaten to wipe out many blue-collar jobs in Britain, the challenges facing a party founded to represent such workers could get tougher and tougher.

A list of candidates in Thurrock is available on the Electoral Commission website.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance