Can Pennsylvania, the birthplace of American democracy, save the country from election chaos?

This election is inescapable in Pennsylvania. On billboards, posters, on television, spray-painted on the sidewalks and walls, and every time you open up a webpage, the volume of political advertisements are overwhelming.

But it isn’t presidential candidates that are taking up the space. Instead, the ads are more often instructions for voters on how to cast their ballot safely and securely in this most unusual of election years. It’s as if democracy itself is on the ballot here. In many ways, it is.

The importance of Pennsylvania to both presidential campaigns is such that it has become the focus of an avalanche of lawsuits, misinformation and fevered speculation about whether it can successfully handle a generation-defining election in the midst of a pandemic.

It is perhaps fitting that this test falls to the state where both the constitution was written and the Declaration of Independence signed. And it is something that people here are taking seriously.

“That does not go unnoticed by everyday Philadelphians like myself,” says Annie Doyle, a 21-year-old community college student who will be working on election day as a poll worker. “It’s the birthplace of American democracy and now we’re really feeling the pressure of preserving it.”

Ms Doyle is one of thousands of other poll workers here in Pennsylvania upon whose shoulders the fate of the entire election may rest. This state is more likely than any other to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden is inaugurated in January. It is also facing one of the most difficult elections in its history.

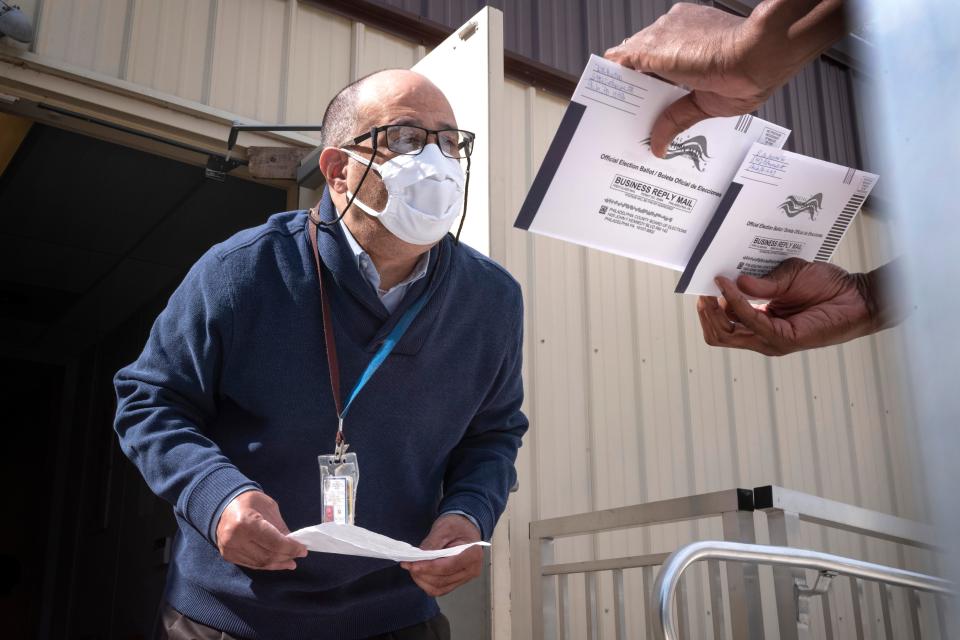

More than 2 million mail-in ballots have been requested in Pennsylvania as a result of the pandemic. The president’s unsubstantiated attacks on the integrity of voting by mail — particularly in this state — have made their smooth processing as high stakes as they come. And a host of changes to voting rules in the last couple of months risks causing confusion and mistakes that could disenfranchise tens of thousands of voters.

Ms Doyle, like many that do her job, takes her role seriously. Her whole family are poll workers — her mum, dad and older sister. Her two younger sisters will follow in their path, too. She has worked in local elections and primaries before, but this is her first general election.

Her job is relatively straightforward. On the day, she turns up at her local polling station early on election day and makes sure voters get the right information, and have the right documents.

“What motivates me to do it now is that our democracy is under attack. There has been a lot of fear mongering, and trying to get people not to vote,” she says.

Election integrity advocates have raised the alarm about the amount of misinformation around the election in Pennsylvania in particular. What makes this year different is that much of that disinformation is coming from the president himself.

Mr Trump has repeatedly suggested that mail-in ballots are vulnerable to fraud in Pennsylvania, without providing any proof. During the first presidential debate this month, he twice mentioned an incident in which an election worker mistakenly discarded nine military ballots in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The president claimed falsely that it was evidence of fraud.

This has added to an atmosphere of confusion for voters, making the job of people like Ms Doyle much more important than in previous years.

“I want to make sure everyone gets their voices heard and takes it seriously. That’s very important to me,” she adds.

The 'red mirage’

One of the biggest differences between this election and previous years for Pennsylvania is the count itself. The dramatic rise in request for mail-in ballots as voters look for a safe way to vote during the pandemic presents a potential pitfall for election day.

The combination of the extra workload in counting these ballots and the president’s attacks on the process has stoked fears of election interference and legal fights.

When the state held primary elections in June — its first during the pandemic — it took weeks to count the extra ballots. A recurrence of that would allow for ambiguity and uncertainty to creep in.

In a worst-case scenario, some fear that Mr Trump may try to use that period to his advantage. The president is likely to take an early lead on election day due to the preference of Republicans to vote in-person on the day. This could create a “red mirage” — the illusion of a Trump lead, which would give Mr Trump an incentive to block the ballots from being counted, using a baseless accusation of fraud to justify it.

Given his focus on Pennsylvania, the state would be a likely candidate for that worst-case scenario.

“We’re going to have to see what happens,” he said last month, when asked whether he would commit to a peaceful transfer of power. “We want to get rid of the ballots, and we’ll have a very peaceful — there won’t be a transfer, frankly. There’ll be a continuation.”

Suzanne Almeida, of the voting rights group Common Cause, says great efforts have been made to manage expectations for the big day to preemptively counter any attempt to muddy the waters.

“We have always been an election night results state. It’s in the culture of the state that if you're willing to stay up late enough and watch the news, they will eventually call the election for Pennsylvania. But that's likely not going to happen this year because of the volume of mail-in ballots,” she says.

“I am particularly concerned that folks — whether it is just voters or candidates, or quite frankly, folks in the media who are used to getting kind of that immediate gratification — are going to look at the fact that we don't have election night results and say something's gone wrong, when in fact it's really that every vote is being counted.”

Election officials are already working to shorten the gap between election day and when results are delivered. They have hired hundreds of extra poll workers to count mail-in ballots. They have also purchased new high-speed scanners to process those ballots.

Commissioner Lisa Deeley, the Democratic chairwoman of Philadelphia’s election board, told The Independent that big changes have been made since the primaries.

“We learned in the June primary that it takes a long time to count thousands of paper ballots, and since then we have industrialised the process and expanded our footprint. I am confident that the votes will be counted in a timely manner, and voters should be confident that the count will be accurate,” she said.

But election advocates have come up against barriers in their efforts to narrow the gap. Republicans in the state are attempting to block a measure that would extend the deadline for mail-in ballots to be received from 8pm on election day to three days after, provided it was postmarked on election day.

Naked ballots and early voting

Election officials across the state have tried to cut down on potential election day chaos by opening up satellite locations where voters can drop off their mail-in ballots early. Seven have opened up across the city of Philadelphia. The hope is that it will cut down on queues on the day and allay concerns from voters that their ballots would get lost in the mail.

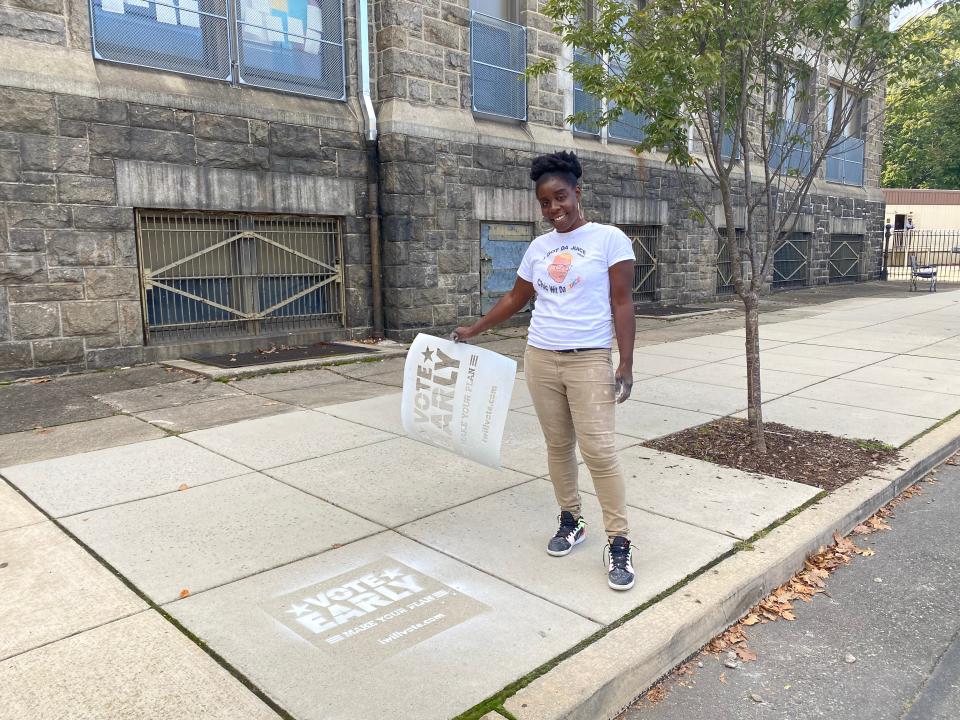

Activists are already turning up at these locations to educate voters and ensure their vote is counted. Nicole Seahorn, who is part of a group called Black Girl Justice League that aims to boost participation, has taken up a spot outside one of them in the neighbourhood of Overbrook in west Philadelphia.

She says they came out to film a public service announcement, but saw that many voters were in need of information.

“These sites are brand new. Thank goodness for these. The postal service is undergoing some difficulties, then we have Covid-19. We have helped quite a few people just get to the ramp because they are old and they wanted to bring in their ballots themselves,” she says.

Other organisations are out there too making sure the process goes smoothly. Next to her is Emma Tramble from My Family Votes.

“A lot of people are afraid. There are misinformation and disinformation campaigns around mail-in voting, around intimidation at the polls. The main thing is, if people have the information they need, I’m finding that alleviates a lot of the anxiety," she says.

“There’s a lot of noise, and it’s intentional.”

Having nonpartisan election officials and information campaigns is essential to prevent widespread voter suppression. This is even more true following a contentious case currently in the courts which could end up disenfranchising up to 100,000 voters, according to some estimates — that is double the margin Mr Trump won by in 2016.

The dispute is over a “secrecy” envelope that goes out with all mail ballots in the state. Last week a court ruled that if voters forget to enclose their ballot inside that envelope — what it called a naked ballot — that vote will be void.

Philadelphia election officials say that if the same number of ballots are rejected for that reason this year than in 2019, some 6 per cent, the number of votes invalidated could be as high as 100,000.

Lawrence Norden, director of voting reform at the Brennan Centre, a voting rights group, said Pennsylvania’s rules are some of the strictest in the country.

“By my count, there are at least 20 states that have something similar to a secrecy envelope. Pennsylvania is the only state that I have been able to find that will not count your ballot if it's not in that envelope or sleeve,” he says.

“You have a situation where you're going to have hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people voting for the first time by mail in Pennsylvania. So they're not familiar with the system and there's this odd rule that seems quite arbitrary,” he adds.

And that is the reason for the deluge of advertisements across Pennsylvania. Those efforts are being paid for by the state, some voting rights groups and the Democrats.

Those efforts, however, are undermined almost daily by the president. He has frequently pushed conspiracy theories and unfounded allegations of fraud in Pennsylvania. At the first presidential debate, he even called on his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully”, raising concerns about voter intimidation.

If they do go, they will meet many people like Ms Doyle. Thousands of people whose job it is to make sure everyone who is eligible to vote can vote without fear.

“It’s a very stressful thing to think about,” she says. “I’m just preparing by not watching too much news and not trying to get too overwhelmed by the fate of our country.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance