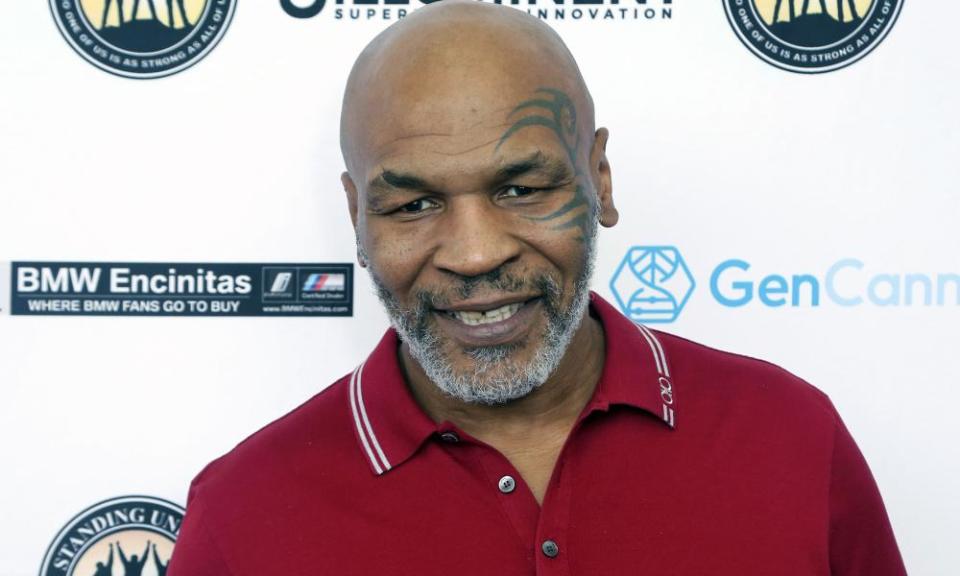

Few should have the stomach for farcical fight between Mike Tyson and Roy Jones

Nobody in the history of paid fighting has used the language of violence with as much undiluted enthusiasm as Mike Tyson. Iron Mike gave credible voice to the expression “bad intentions” and, from 1985 until 2005, he scared the pants off 50 lesser mortals until he began to rust and they started beating him up.

Yet, on his return to the ring at 54 in the Staples Center in Los Angeles on Saturday night, the man who once threatened to ram an opponent’s nose bone into his brain and said he would eat Lennox Lewis’s babies (he didn’t), is being asked to collude with fellow 50-plus retired pugilist Roy Jones Jr in the biggest public love-in California has seen since hippies hugged in Haight-Ashbury in the 60s.

All week we were told Tyson, after 15 years of peaceful retirement, and Jones, who last fought two years ago, would be unable to do what they once were so good at: knocking the other guy unconscious. By Friday, nobody was sure, and it is entirely possible these fistic pensioners will yet try to tear each other’s heads off. If they can land a punch.

One thing we know: this is not a sanctioned fight, but an exhibition. They will move around in front of each other for eight two-minute rounds wearing 12oz gloves, shift their rusty shoulders into position and, depending on whether we believe the California State Athletic Commission, who insist the fighters will be discouraged from trying to seriously hurt each other, or the promoter, Ryan Kavanaugh, who is indignant at such a suggestion, it will be a bust or a brawl.

It will be intriguing to listen to the referee’s instructions when he calls them to centre ring: “Gentlemen, I gave you your instructions in the locker room, so defend yourself at all times, touch gloves – and, whatever you do, don’t come out fighting.” And you can watch it. All you need is a brain the size of a pea and a bank card that will allow you to pay an easily identified British TV channel £19.95. In the United States, where truth is a negotiable commodity, they are asking nearly $50.

This lucrative tale of woe began with Tyson in May when – bored, intoxicated, impecunious or all three – he posted on Instagram: “The gods of war have reawakened me, ignited my ego and want me to go to war again.” An Australian promoter immediately tried to line up a string of $1m fights for him against rugby players, including Sonny Bill Williams, who is a serious item with gloves on. Nothing happened. There was talk of a bareknuckle fight against Peter McNeeley, the patsy who fell over in front of him in 1995. Nothing happened. Evander Holyfield, who lost a slice of his ear to Tyson but won both their fights, got interested. Nothing happened.

Related: Lennox: The Untold Story review – a ringside seat for the rise of a champ

When this show was announced in July (originally headed for the Dignity Health Sports Park, a short drive from Disneyland and not a long way from self-parody), Andy Foster, the executive director of the CSAC, was moved to warn: “We can’t mislead the public as to this is some kind of real fight. They can get into it a little bit, but I don’t want people to get hurt. They know the deal.”

It is hard to imagine that on a promotional poster. We don’t expect the truth, because we have become desensitised to embellishment and deception – but at least go through the motions, guys. It is part of boxing’s dubious charm. In its latest iteration, however, boxing does not much resemble its ugly, bare-fisted roots.

Tyson knows the history of his business better than most, and one of his favourite fables is a heavyweight fight in a field in Farnborough 160 years ago, an occasion that could hardly be more at odds with the sham Rusty Mike and his pal are involved in this weekend.

At dawn on a crisp spring morning in 1860, 12,000 patrons waved two-guinea tickets marked, “to nowhere”, as they scrambled on to trains out of Waterloo, a comical ruse to throw the constabulary off the scent as they headed into the Hampshire countryside to witness the first international contest for a world title.

It was a finish fight at heavyweight with no gloves between Tom Sayers, the illiterate son of a Brighton cobbler, and a leg-breaking American debt collector called John Heenan.

As in LA this weekend, there were rules of a sort: no eye-gouging (nice), or “cross buttocks” (of course), just acceptable semi-murderous intent that lasted two hours and 47 minutes in front of a mob that included William Thackeray and Charles Dickens, with news of the entertainment relayed back to the Prince of Wales and the prime minister. We really were all in it together in those days.

When the Peelers arrived to disperse the gathering, forcing the cancellation of all bets, Heenan staggered into the distance, half-blind. Sayers escaped to catch a train back to the Old Kent Road, where he drank champagne to celebrate surviving and a half share of £400. He never fought again.

Heenan fought on without distinction then died alone and gasping for air in a Wyoming hotel at the age of 38. Five years after their fight, Sayers had 30,000 at his funeral in Highgate (where he still lies). He was 39. For once, the language of fist fighting had not outpaced the deed.

Times move on. When Kell Brook got into the best shape of his career to challenge the formidable Terence Crawford two weeks ago, he did not, as he promised, go out on his shield, but on unsteady feet, rescued from two brutal and clinical assaults. It was as it should be. And in 1939, there was no chance that Two Ton Tony Galento would be able or allowed to “moida da bum”, as he declared he should have done when he briefly shared a ring with the peerless Joe Louis.

No, there are no designated shields or murders in boxing, just controlled heroism, often excessive bravery and occasional tragedy. For one more night, we can add farce.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance