Forget the wolf warrior: Australia still needs to know the truth about Afghanistan

If you were utterly transfixed by the diplomatic conflagration between China and Australia this week, it’s possible you missed the other significant political bushfire the Morrison government was battling in the background.

It’s worth stepping through all the elements of this story.

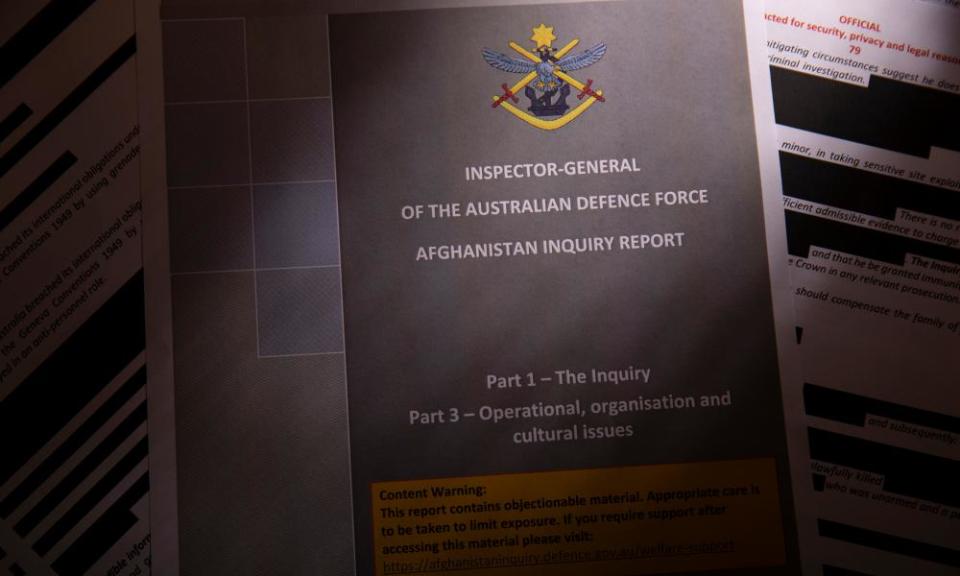

Before Zhao Lijian fired off his offensive Tweet early in the week, featuring the manufactured image of an Australian soldier cutting a child’s throat, we had the Brereton report: the investigation into alleged war crimes perpetrated by our special forces in Afghanistan.

You’ll likely recall Brereton was preceded by weeks of speculative build up. The report was obviously going to be bad, because Scott Morrison felt the need to prepare Australians for the findings. In the middle of last month the prime minister flagged that a special investigator would be appointed to consider criminal cases because the looming investigation would contain “very difficult” and “disturbing” allegations.

Related: What is China's endgame? That's the question Australia has no answer to | Katharine Murphy

The Brereton findings, when they lobbed, were exactly that: disturbing, nauseating even. The investigation found credible evidence that 39 Afghans had been killed unlawfully in 23 incidents, either by Australian special forces, or at the instruction of special forces.

But having choreographed the prelude the week before, on the day the report was actually released, the government staged an on-brand retreat. Senior figures vamooshed, leaving the chief of the defence force, Angus Campbell, to own the devastating findings in all the television news packages.

Campbell, during his solo performance, flagged a number of measures in response to Brereton, including stripping SAS soldiers of medals. The meritorious unit citation awarded to Special Operations Task Group rotations serving in Afghanistan between 2007 and 2013 would be revoked.

Outrage from some veterans and some in the general community ensued. The first line of outrage was the top brass seemed inclined to censure soldiers in the field while casting themselves as innocents. The second fracas was around the recognition: why should everyone lose their medals because of the bad behaviour of the few?

Fearing a brewing political disaster, the government reappeared as quickly as it had vanished, and began micromanaging, first quietly, then noisily.

Late last week, Morrison told a radio station no decisions had been made about stripping the medals. By last Sunday, the ABC’s Insiders program was reportedly given a statement from the Department of Defence saying the final decision about the citations would be a matter for the government. By Monday night, Campbell confirmed he was no longer driving the Brereton bus.

By Wednesday, Alan Jones had hit full screech.

Jones opined in the Daily Telegraph (in a piece headlined Alan Jones: Scott Morrison gave China the opening) that the Chinese foreign ministry was able to post the grossly offensive image of the soldier and the child because – wait for it – Our Prime Minister had reflected negatively on Our Troops in the lead up to the release of the Brereton report.

Morrison had allegedly “defamed thousands of innocent, courageous and heroic Australians whom we sent to Afghanistan to put their lives on the line in our name”.

This hyperventilation was so preposterous a reasonable response would have been laughter.

But Jones is considered trouble, and by Thursday, Andrew Hastie, a former special forces soldier and head of parliament’s joint committee on intelligence and security, was in the House rebutting Jones and defending Morrison. A counter-operation was mounted. Hastie pointed to the early release of the Crompvoets report.

If you’ve missed this bit of the jigsaw, the military sociologist Samantha Crompvoets produced a report in 2016 that triggered the four-year Brereton investigation. The Brereton report then referenced details of Crompvoets’ interviews with special forces soldiers, including “an incident” where she was told “members from the SASR were driving along a road and saw two 14-year-old boys whom they decided might be Taliban sympathisers. They stopped, searched the boys and slit their throats.”

Hastie told the chamber that material – the “unproven rumours of Australian soldiers murdering Afghan children” – should never have been put in the public domain. He said the sociologist’s report had triggered Brereton “but its evidentiary threshold was far lower”.

Related: WA Museum Boola Bardip denies changes to China display were due to political pressure

“The Brereton report neither rules these rumours in nor rules them out, so why are they out in the open for our adversaries to use against us?” Hastie said on Thursday night. “It has undermined public confidence in the process and allowed the People’s Republic of China to malign our troops.”

Hopefully this quick recap has given you the picture: the government was battling to bed down Brereton under the cover of an explosive tweet from China’s foreign ministry, and all the feelings about the tweet that punctured the round-the-clock news updates.

In a strange sort of way, Zhao’s obnoxious state-sanctioned trolling was useful to Morrison, at least in the Churchillian spirit of never wasting a good crisis.

Firstly, China’s undiplomatic diplomacy furnished Morrison with a dignified way of appearing in public to humbly request that the leadership in Beijing pick up the phone. This appeared to be the prime minister’s principal purpose in responding to the tweet. Ostensibly Morrison appeared to demand an apology for the egregious affront, but actually, the script was we’ve hit rock bottom now, so let’s reset. A prime ministerial overture like that would have looked like weakness in the absence of a catalyst.

The second way Zhao’s trolling helped was by creating a diversion. The domestic aftermath of Brereton was getting seriously messy – in part because the government couldn’t decide whether to sit it out or stage-manage it – but perhaps people wouldn’t notice given the public debate was focused on what China shouldn’t have done rather than what the government was struggling to do.

But the problem with rolling diversions is they can obscure substance.

When it comes to the Brereton investigation, we do need to screen out the noise, and remain resolutely focused on the substance.

Lost in the melee of the week – in all the public outrage about China being a bully, in the “enough about you, more about me” fulminations of Jones and the damage control unleashed in response – is a simple fact.

There are credible allegations that Australian special forces committed war crimes in Afghanistan.

As well as the alleged murders and two instances of “cruel treatment” carried out by 25 Australian perpetrators either as principals or accessories, included in Brereton’s catalogue of horrors was a practice known as “blooding”.

Junior soldiers were allegedly required by their patrol commanders to shoot a prisoner in order to achieve their first kill. Brereton says this apparently normalised culture of extra-judicial killing was “reinforced with a code of silence”.

Rather than worry minutely about what a wolf warrior “diplomat” from Beijing is saying to try and get a rise out of the political class in Australia, it’s better we focus collective energy on what went wrong in Afghanistan, and why.

Related: 'Double-bind': Chinese-Australians face difficult times as tensions grow

We can summarise the moving parts in this way.

Given the human rights atrocities that occur on the watch of the authoritarian regime in Beijing, China is in no position to criticise Australia for its record in Afghanistan. If Chinese forces faced similar allegations, nobody would ever know about it, because truth isn’t tolerated in the people’s republic.

But Australia also needs to remember this: something went badly wrong in the culture of our most elite military personnel. We need to understand what, and why.

Getting to the bottom of the Brereton allegations, not rationalising them or airbrushing them, insisting on accountability up and down the chain of command and on facilitating rigorous rule-of-law processes that allow any war criminals to face fair trials, having people either answer for what they have done or be exonerated if they are innocent, is critically important.

Because at the end of the day, the capacity to seek the truth is the thing that separates a liberal democracy from a belligerent autocracy with a sideline in cheap shitposting.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance