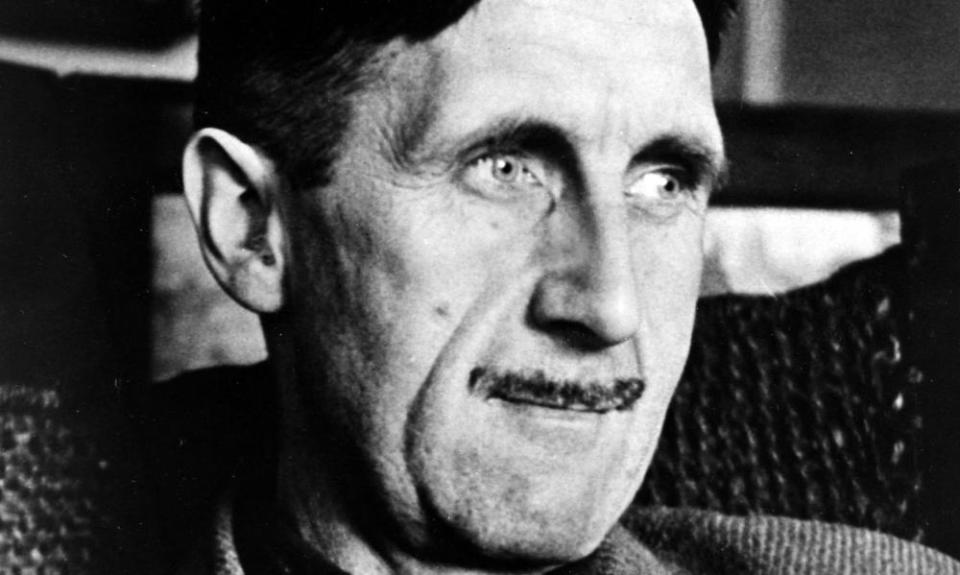

George Orwell is out of copyright. What happens now?

George Orwell died at University College Hospital, London, on 21 January 1950 at the early age of 46. This means that unlike such long-lived contemporaries as Graham Greene (died 1991) or Anthony Powell (died 2000), the vast majority of his compendious output (21 volumes to date) is newly out of copyright as of 1 January. Naturally, publishers – who have an eye for this kind of opportunity – have long been at work to take advantage of the expiry date and the next few months are set to bring a glut of repackaged editions.

The Oxford University Press is producing World’s Classics versions of the major books and there are several bulky compendia about to hit the shelves – see, for example, the Flame Tree Press’s George Orwell: Visions of Dystopia. I have to declare an interest myself, having spent much of the spring lockdown preparing annotated editions of Orwell’s six novels, to be issued at the rate of two a year before the appearance of my new Orwell biography (a successor to 2003’s Orwell: The Life) in 2023. As for the tide of non-print spin-offs, an Animal Farm video game hit cyberspace in mid-December.

As is so often the way of copyright cut-offs, none of this amounts to a free-for-all. Any US publisher other than Houghton Mifflin that itches to embark on an Orwell spree will have to wait until 2030, when Burmese Days, the first of Orwell’s books to be published in the US, breaks the 95-year barrier. And eager UK publishers will have to exercise a certain amount of care. The distinguished Orwell scholar Professor Peter Davison fathered new editions of the six novels back in the mid-1980s. No one can reproduce these as the copyright in them is currently held by Penguin Random House. Aspiring reissuers, including myself, have had to go back to the texts of the standard editions published in the late 1940s, or in the case of A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying, both of which Orwell detested so much – he described the former as “bollox” – that he refused to have them reprinted in his lifetime, to the originals of, respectively, 1935 and 1936.

Neither will anyone be allowed to trespass on all the material that came to light post-1950 and which Davison painstakingly assembled in his compendious George Orwell: The Complete Works (1998). This includes Such, Such Were the Joys, the notorious account of his tribulations at a character-forming Sussex prep school, first published in the US in 1952 but not issued in the UK until as late as 1968, for fear of libel proceedings. The proscriptions also apply to such tantalising items as the letters of Orwell’s first wife Eileen, which Davison prints in The Lost Orwell (2006). They also cover the two substantial caches of Orwell letters that came to light in 2018 and which Orwell’s son Richard Blair has recently presented to the Orwell Archive at UCL.

On the other hand, any dramatist or film-maker or computer-gamer or “Wit and wisdom of …” compiler who wants to set about Animal Farm or Nineteen Eighty-Four can, effectively, do what they like. Of the many failed attempts to bring these novels to stage or screen, a particular highlight was David Bowie’s early 1970s effort to create a musical of Nineteen Eighty-Four, which failed at the hurdle of Orwell’s widow Sonia, who expressed her severe displeasure. A few fragments of the project survive in the songs included on Diamond Dogs (1974). It’s a shame that Bowie never got to realise his dream. Who knows – perhaps the Arctic Monkeys’ Alex Turner, whose very first single included a reference to “a robot from Nineteen Eighty-Four” is already hard at work?

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance