Goals, class, a red Ferrari: Aldridge, Richardson and Atkinson at la Real

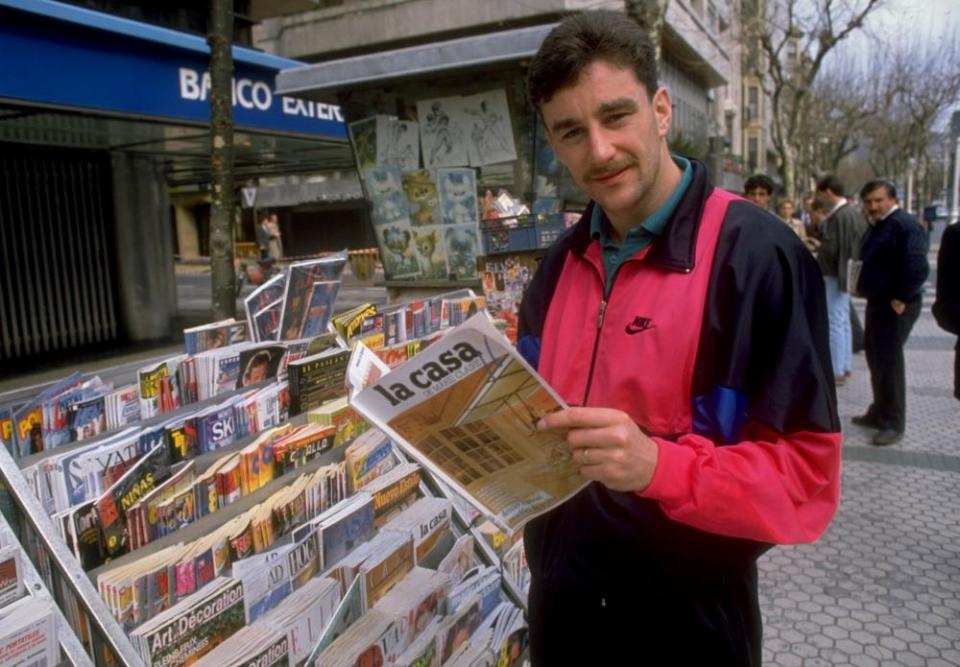

The day John Aldridge turned up at Real Sociedad’s Zubieta training ground in September 1989, he was confronted by graffiti saying foreigners weren’t welcome. A year on, he had been so good that they welcomed two more of them, this time with open arms. For almost 30 years, la Real didn’t have a player from outside the Basque Country; now they had three, and all from Britain and Ireland.

They were in San Sebastián together for only a season and not even a particularly good one, la Real finishing 1990-91 in their lowest position since returning to the first division 22 years earlier, but Aldridge, Kevin Richardson and Dalian Atkinson left an indelible mark, says Jonan Larrañaga. “I have lovely memories of all three,” the then club captain adds. Whoever you ask there is warmth. No one scored more goals than Aldridge or Atkinson and only Larrañaga played more games than Richardson.

Related: Real Sociedad's Mikel Merino: 'I am who I am because of the Premier League'

And then they were gone again.

Larrañaga describes Aldridge’s arrival as “the bomb”. Confronted by a changing market and key departures the president Iñaki Alkiza proposed a radical shift in policy. Passed by 75 votes in favour, 21 against and five abstentions, for the first time Real Sociedad would sign foreigners. (Another 10 years passed before they signed a non-Basque Spaniard.) Aldridge walked into a social and political storm he couldn’t understand.

“It was historic, very special,” teammate Luis Dadíe recalls. “A lot of people were against it. It could have been hugely controversial, but in the end it wasn’t traumatic because Aldridge had so much personality, approached it so naturally and transmitted so much character on the pitch that the fans embraced him and he became ‘one of us’ immediately. A different player with a different personality, who hadn’t played so well – don’t forget Aldo scored 22 that season – couldn’t have done that.”

“We were lucky because John was a great player and a magnificent teammate,” says defender Alberto Górriz. Richardson and Atkinson were even luckier; by the time they arrived a season later, not being Basque was no longer an issue. “Aldridge was the litmus test,” Dadíe says.

Real Sociedad paid 150m pesetas for Atkinson and 135m for Richardson, joining a squad made up of one Republic of Ireland international and 26 Basques, including current manager Imanol Alguacil.

La Real’s players knew a bit about Richardson but very little about Atkinson. They soon found out. “In all the [14] years I was at la Real, the player with most talent was him,” Górriz says. “He was special, the strongest player I’ve ever seen.”

“He had a huge impact,” Dadíe says. “It was absolutely marvellous watching him. He left us open-mouthed. Dalian was a modern player: direct, so fast, he could run with the ball, carry it, take people on. It was incredible. In our age, we hadn’t really seen players like that. These days, that would be pure gold.”

Atkinson was the club’s first black player and one of very few black people in the city. He became known as Txipirón, the squid, because of its ink. One teammate recalls Atkinson saying people looked at him, but relating that more to his fame and red Ferrari. Atkinson told Marca he never felt “any discrimination, just affection”.

“People were wild for him,” Dadíe says. “It was like he was our first superstar. We’d had players like Arconada, Zamora, Satrústegui, López Ufarte: imagine what they meant to this city. Well, Atkinson provoked three times the passion. People were crazy about him, he was very special on and off the pitch. I haven’t seen the fans get off their seats like they did with Atkinson. He was different, an absolute crack when he was at his best.”

When he was. That season, Real Sociedad won at Barcelona, Real Madrid and defeated Atlético at home. Atkinson scored against Madrid, Barcelona, Atlético, Valencia and in the derby against Athletic. He got as many goals against them as against the rest put together. He didn’t always follow orders – “the coach could say ‘cover the full-back,’ and you might as well tell him to go to the cathedral for mass,” Dadíe says – and other teams were, well, other teams. Especially if they weren’t on television.

“Atkinson was sensational when he wanted to be,” says Mitxelo Olaizola, Real Sociedad’s kit man for 37 years. “I remember we were going to Burgos, away. ‘Mitxelo, what’s Burgos like?’ ‘Small ground, small city, cold.’ ‘Ah, then I’m not going.’ And he didn’t.”

Atlético Madrid were so impressed they came with “big offer”, Górriz recalls. “We won at all the big grounds where he was really motivated. Him and Aldridge up front: machines. In other games, he didn’t perform so well. Atlético came, but for some reason [nothing happened]. I don’t know if they had some information that they didn’t like.”

Atkinson was 21 upon arrival. “He would cover his legs in Vaseline and say, ‘That’s my warm up done’,” Mitxelo recalls. He would go out on the town and still be the best in training. There wasn’t much they could say, although many tried. Ultimately, his talent went unfulfilled.

“The fans were wowed by him, but they would also see him out in the small hours,” Larrañaga recalls. “In the end, his youth got the better of him. I spoke to him a lot, I was the captain, one of four or five veterans who tried to get him in line, but he did things his way. He was like a little brother you had to be on top of. He needed that help and we tried to give it to him.”

A story, which the players can’t confirm, is told in San Sebastián that one day Atkinson was presented with an Idiazabal cheese by a supporters’ club, only to throw it out of the car window, sending it rolling down the road. He had at least two crashes. After one, he drove off – as if the city’s greatest celebrity, a famous footballer in a red Ferrari, would be hard to identify.

“My private life is my own,” Atkinson told Marca that January, during an interview in which he was bluntly told: you’ve failed. “I’m 22, I can’t sit at home watching television,” he insisted, noting that for “some people, especially journalists, everything I do is bad”. He, Aldridge and Richardson were fined after being at a nightclub at 6am. Atkinson’s parents had wanted him to go home, something made more poignant by the psychiatric health problems he later suffered and his tragic death in August 2016. He went into cardiac arrest as he was taken to hospital after being restrained and Tasered by police officers.

“I don’t know if it was our fault; maybe we didn’t manage to guide him as we could have,” Górriz says. “I think we gave everything but we couldn’t get him to see how important it was to look after himself. I always think about him. I used to get changed next to him and I would have a go at him, try to get through, even grabbed him once. ‘Bloody hell, Dalian, you have to play like this every week.’ But I could see him looking at me, like: ‘Eh?’

“And he told me he had what he wanted: he was from a humble family, he liked cars, he had the cars he wanted – all of them red sports cars, which he loved – he had friends, he had family and that’s what matters in life. He said there were pretty girls here. He was a lovely lad.”

At the end of the season, John Toshack returned as coach with his own ideas. He had little affection for Atkinson, Aldridge and Richardson. Their short spell was over, having finished 13th, three points above the relegation zone. “Dalian, John and Kevin rescued us,” Larrañaga says. “Kevin was a great man and a great player. Dalian gave us a lot, so did John.” Aldridge had scored 17, Atkinson 12. Richardson had played 37 of 38 games.

Dadíe says: “It was only a year but they all left such a mark.”

“People might not have noticed Kevin as much because he was in between two players who really captured people’s attention,” Górriz says. “He was calmer, mature, a great professional. He didn’t stand out but he always played well, and teammates appreciated him. And John was a phenomenon, the one we’ve kept in touch with the most.”

“I went to Zubieta one day not long after they left and a removals van turned up, driven by an English bloke,” Górriz continues. “He had come for some of Dalian’s stuff; he had left things behind at a clothes shop or something. People had that image of him, and that’s what upsets me. There wasn’t a bad bone in him. It saddens me that people remember the car more than the player who had us all watching in wonder, the guy who liked to go out rather the great footballer he was, what a big heart he had. I wish things to have gone better for him in football … and in life.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance