Great Estates: How Glyndebourne saved the lives of hundreds of evacuees

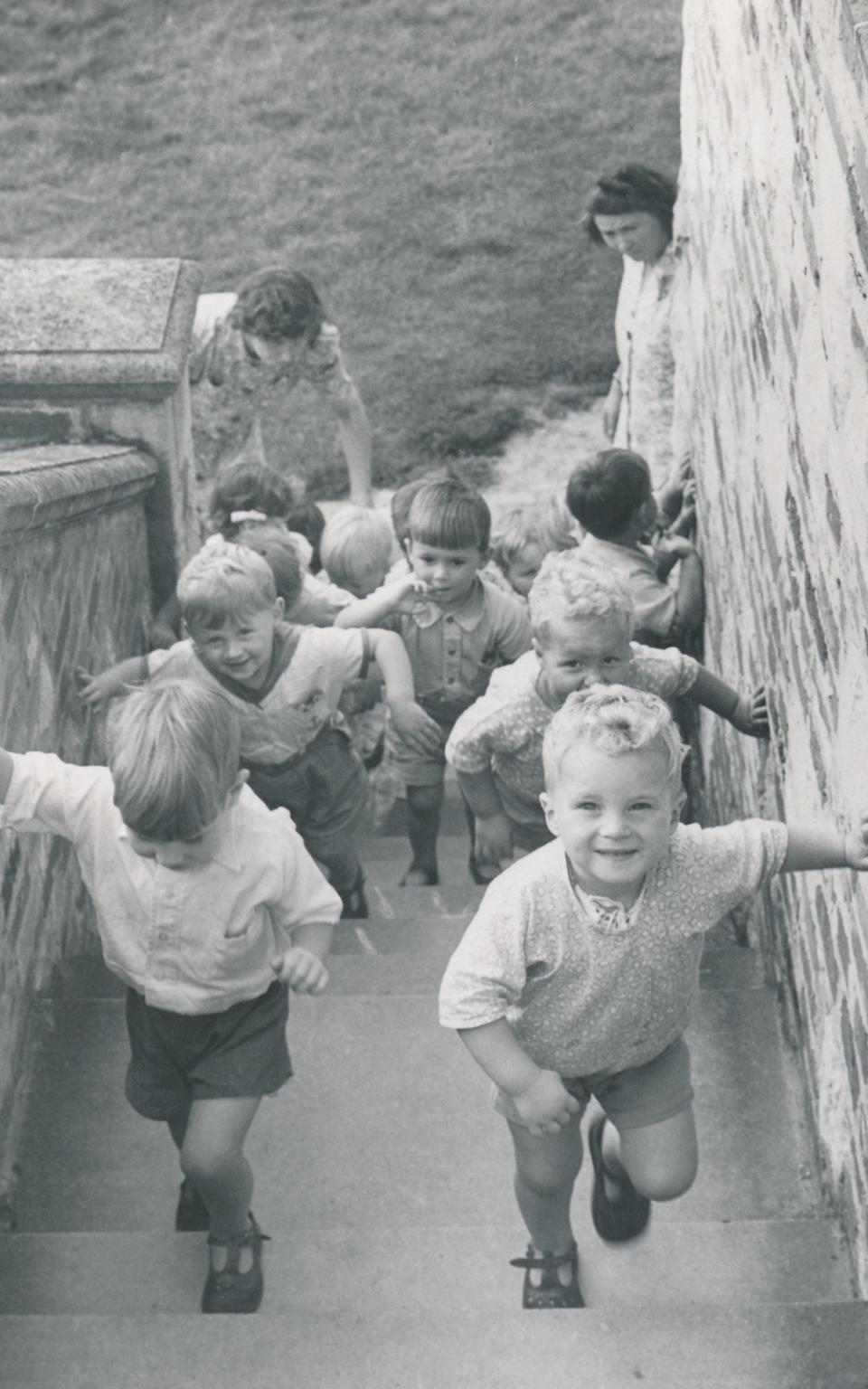

The day before war broke out in September 1939, a chug of red London buses descended upon Glyndebourne in East Sussex. Out clambered hundreds of toddlers. The Tudor mansion was to be their new home. For all its operatic history, the real high note in Glyndebourne’s past is its role saving hundreds of young lives during the Second World War. And yet it is also its best-kept secret.

There’s a nod to it at this year’s Glyndebourne Festival with a production of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos set during one of the bleakest times in British memory. The German director, Katharina Thoma, was inspired by the transformation of Glyndebourne into a centre for evacuees during the war. Opera performances were on hold until 1946. The production is inspired by history, but does not reproduce it – on stage, Glyndebourne becomes a hospital for wounded soldiers.

I remember playing hide and seek behind the privet hedges, spotting the flamingos hiding behind the trees by the lake and making snowballs with the other children

Neil McCarraher

What of the real story? Who thought that a grand country estate known for its high art – the first Festival was in 1934 – would be a suitable place for children? Julia Aires, Glyndebourne’s archivist, credits Mr W E Edwards, the estate manager at the time, for the idea. “It was a masterstroke on his part,” she says. “He was terrified that Glyndebourne was going to go the way of other country houses – that the Ministry of Defence would take it over and bash it about – so he offered it to the London County Council as a home for evacuees instead.”

And so it was in September 1939, that boys and girls from five places in south London – two day nurseries, one privately run babies’ home, one council institution for babies mainly of unmarried mothers and a nursery school in Peckham – found themselves in another world. Marguerita Fowler, secretary to Mr Edwards, remembers how the front lawn that day was crawling with babies.

Nursery carers soon realised that Glyndebourne couldn’t cope with quite so many little guests. Some of the babies were taken in by local families, leaving about 100 boys and girls aged between two and five from the original 300. When the children turned six, they would be billeted around the country, while a steady influx of new children would join over the next six years. They lived in the Front Hall of the house; the Plashett Huts, an outbuilding for waiters during the opera festival; and the old Green Room. The Green Room, a room with an oriel window at one end overlooking the garden, was the dressing room to the stars. One group of children slept in Female Chorus, Matron was in Wigs.

Neil McCarraher, now 83, was four when he arrived at Glyndebourne with his sister Dena, then two, and brother Michael, just one. “I had a very happy time,” he recalls today from his home in Weybridge, Surrey. “Being one of the eldest there, the staff virtually let me have the run of the house and the gardens. I remember playing hide and seek behind the privet hedges, spotting the flamingos hiding behind the trees by the lake and making snowballs with the other children.” Neil even met John Christie, the owner. “Mr John took me on as a little friend. He was a lovely man. He used to potter around in the kitchen garden and help me dig my own vegetables.”

Christie felt it was essential for the children to escape the smog and wartime terror of London for the green fields, and the children were encouraged to run around outside, taking gulps of fresh air. One account describes a boy spotting cows opposite the house and going, “Cor! Don’t they have big dogs in the country.” Another, in The Lady magazine in 1943, tells of children seeing cows being milked for the first time and milking the air on the way home. Children were also allowed to hold newborn lambs in the spring. “One child who had refused up till then to open his mouth or make friends turned scarlet with ecstasy when he found himself clasping a lamb, and was happy and normal from that day,” writes the journalist.

It was a strange site for an evacuee centre because it was under one of the main bomber routes

Julia Aires

Neil left Glyndebourne when he turned six, staying first with his grandmother in Liverpool, before being billeted to Leatherhead and Woking until the end of the war. “I loved Glyndebourne most of all,” he says. He went on to work in the equestrian industry and retired last year.

Neil’s memories prompted him to contact John Christie’s son, George, when he took over the running of the house in 1962, and then Gus, John Christie’s grandson, its current owner, who took him on a tour of the house. “Glyndebourne hasn’t really changed a lot in my eyes,” he says.

While the house and grounds might look much the same, details of daily life might surprise anyone who associates Glyndebourne with champagne-quaffing picnics. It would be a brave festival programmer who recommends operagoers bring this sort of food in their hampers.

While rationing at Glyndebourne was more relaxed because it was an evacuee centre, ingredients were still limited. Children and staff ate rabbits from the fields, eggs courtesy of local farmers (and hens), and rosehips, blackberries and elderberries that they picked from the hedgerows in the grounds. They had breakfast, a hearty lunch and a snack supper.

The cook, however, only had two very antiquated four-ring gas cookers and a tiny fridge so making anything elaborate was difficult, explains Aires. Dishes included boiled beetroot in a white sauce, Brussels sprouts on toast, and mashed potato stirred through with powdered egg. She says: “I imagine if you were a hungry child who had been running around the garden all day you’d probably eat anything, but it sounds utterly grim.”

There was also the logistics of looking after 100 small children. Mrs Wheeler, a London County Council matron, was in charge, and went by the severe name of “Commandant”. She encouraged self-sufficiency – even the two-year-olds were said to feed and dress themselves. But there were warmer touches, too. A charming account, again in The Lady, records how each child was given a motif to help them identify their possessions: “Ronnie may have a puppy, Mary a kettle, John an apple, Gloria a butterfly, Brian a teapot. This is embroidered on to pillowcase, towel and face cloth, stencilled in a bright colour… on to a toothbrush and a potty, and painted on the cloakroom wall above his peg.”

Such order and organisation stuck in the mind of Jean Bargeman, who passed away aged 72 four years ago. Her husband, Norman Woodward, 79, who lives in East London, says: “She used to tell me it was very strict and everything had to be spick and span. She was in a dormitory with lots of small beds. Everything had to be folded up all neat and tidy. When I got married, my wife was like that: she folded everything up. But I know she was grateful for her time there. Her mother died when she was two months old. The ladies there took care of her. Glyndebourne was her home.”

As for Glyndebourne, the house emerged from the war with barely a scratch. It wasn’t until the early Nineties, when the new opera house was being constructed, that builders found cards and pages from comics that young evacuees had posted through the gaps in the floorboards. One is a beautifully illustrated cover of an ABC book inscribed with the words “Billy, with love, Gran, 1941.”

For the hundreds of children who passed through its doors, many of whom had been used to air raids and the rubble of London, Glyndebourne was a refuge. Perhaps most miraculously is that the house was safe at all. “It was a strange site for an evacuee centre because it was under one of the main bomber routes,” explains Aires. “But John Christie firmly believed Hitler would never ever bomb Glyndebourne because, in his words, ‘Hitler respects us too much.’ Glyndebourne’s music director Fritz Busch and its artistic director Carl Ebert had fled Germany, but the Nazi regime desperately wanted them back because they were so admired in musical circles. John knew it would be safe.” Thankfully for hundreds of evacuees – and opera lovers – he was right.

Glyndebourne Festival runs from May 20 to August 27. Telegraph readers can take advantage of priority booking until Saturday, see telegraph.co.uk/go/glyndebourne for details.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance