What happened to Titanic's richest passengers

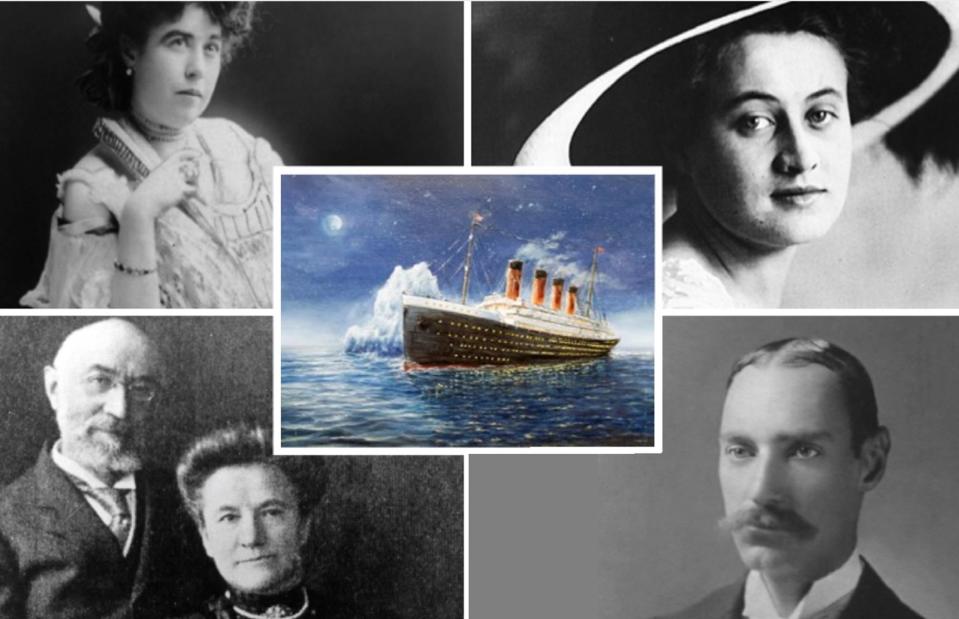

Who were the richest people onboard the Titanic?

Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain / Boyan Dimitrov/Shutterstock

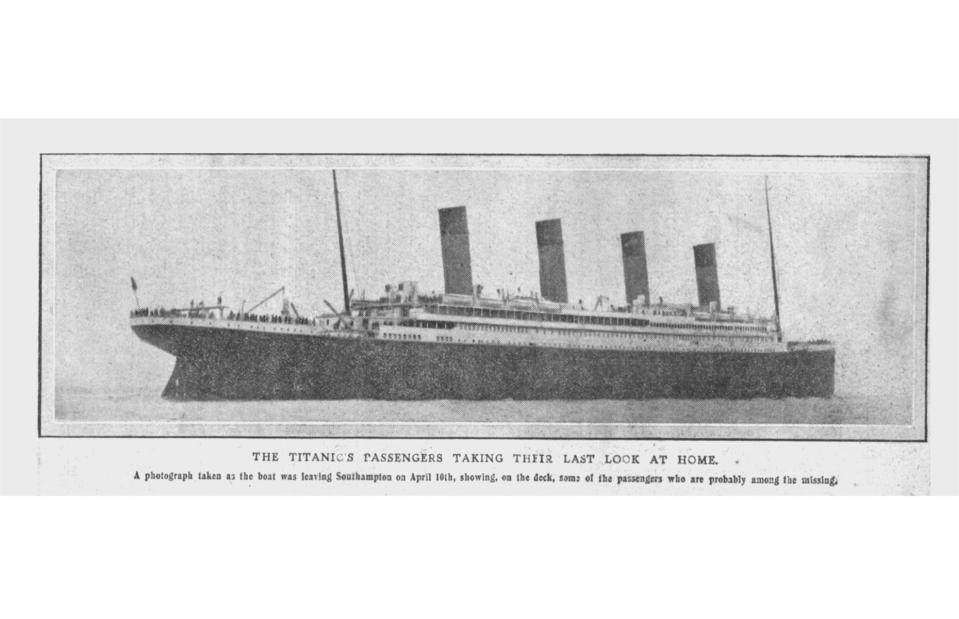

In the early hours of 15 April 1912, more than 1,500 people lost their lives on the ‘unsinkable’ Titanic. Although 60% of first-class passengers survived, some of the world’s richest people were lost to the waves, although not from the history books.

From the co-owner of Macy's department store to the richest man in America, read on as we tell the incredible stories of the super-rich who sailed on the Titanic. All dollar values in US dollars.

Dorothy Gibson

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Gibson was a silent film actor, singer, and artist’s model. She made her film debut in 1911, appearing as an extra before landing her first leading roles.

Although her net worth isn’t known, Dorothy was reportedly one of the highest-paid actresses at the height of her career. Mary Pickford, the highest-paid actress at the time, earned $500 a week in 1913 – the equivalent of over $14,000 (£11k) today.

Dorothy Gibson

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

Following a holiday to Italy with her mother, Dorothy caught the Titanic to return to America where she was due to start filming. She was playing bridge in the first-class lounge when the ship struck the iceberg.

While many passengers were unaware their lives were in danger, Dorothy and her mother escaped in Lifeboat #7, the first lifeboat that launched, and were taken to New York by the rescue steamship Carpathia.

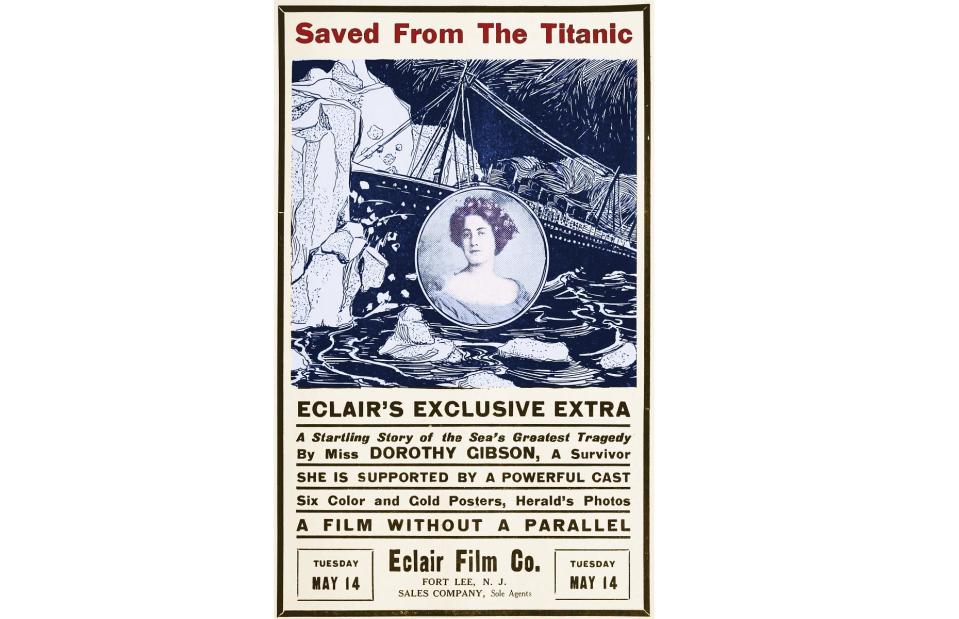

Dorothy Gibson

Eclair Film, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One of Dorothy’s most successful films, A Lucky Holdup, was released in April 1912 while she was aboard the Titanic. It wasn’t long before her next hit.

Convinced by her manager, Dorothy starred in and wrote Saved from the Titanic, a short silent movie documenting her escape. Her costume for the film? The very same silk dress, cardigan, and coat she wore on the night of the tragedy.

Margaret (Molly) Brown

Bain News Service; quick cleanup by Adam Cuerden, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Unlike many of the other people we'll look at, Margaret Brown wasn’t born rich. The daughter of Irish immigrants, she lived with her siblings in Leadville, Colorado, and had a job in a department store. In 1886, when she was 19 years old, she married James Joseph ('J.J.') Brown.

Margaret lamented the fact he wasn’t rich and couldn’t support her parents financially, but "decided that I’d be better off with a poor man whom I loved than with a wealthy one whose money had attracted me".

Margaret (Molly) Brown

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

This decision paid off – literally. In 1893, J.J. discovered gold and copper ore at the Little Jonny Mine and his employer, the Ibex Mining Company, rewarded him with 12,500 shares in the company and a seat on the board. The Browns became incredibly wealthy almost overnight.

After 23 years of marriage and with two children together, Margaret and J.J. eventually separated in 1909 but remained on good terms. As part of the divorce, Margaret received an allowance of $700 a month. Today, that’s the equivalent of over $20,000 (£15.7k) a month or $240,000 (£188k) a year. Pictured is the parlour at the Browns’ family home in Denver, now the Molly Brown House Museum.

Margaret (Molly) Brown

National Museum of the U.S. Navy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In April 1912, Margaret was on holiday in Europe when her grandson suddenly fell seriously ill. Searching for the fastest passage back to New York, she bought a first-class ticket on the Titanic. Some reports claim the other first-class passengers looked down on Margaret as she came from "new money".

However, when the voyage took a disastrous turn she won respect for her role in helping others escape. As well as encouraging lifeboats to turn around to look for people in the water, Margaret organised a committee after the tragedy to provide support to second- and third-class survivors. Pictured here awarding a trophy to the captain of rescue ship the Carpathia, she was dubbed "the unsinkable Molly Brown" for her bravery.

Charles Melville Hays

Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Charles Melville Hays made his fortune as the president of the Grand Trunk Railway, a North American rail system connecting Canada and the US. During his 45-year career, the philanthropic Charles received accolades including the Order of the Rising Sun (third class) and was even offered a knighthood.

But his life took a stressful turn in 1911 when the transcontinental railroad he was working on racked up eye-watering debts of $100 million, the equivalent of $2.8 billion (£2.2bn) today.

Charles Melville Hays

Stephen Bridger/Shutterstock

Charles went to England in early 1912 to discuss financing options with his British business associates, taking his wife, daughter, son-in-law, secretary, and maid with him. But by April, he was anxious to return to North America – partly to attend the opening of the Château Laurier hotel in Ottawa (pictured here in 2014) and because one of his other daughters was having a difficult pregnancy.

J. Bruce Ismay (more on him later), chairman of the White Star Line shipping company that owned the Titanic, personally invited Charles to join him on the ship's maiden voyage.

Charles Melville Hays

Michel Boutefeu/Getty Images

Charles and his party shared a deluxe first-class suite, probably similar to this replica built at the California Science Center. However, they didn't get to enjoy the luxurious lodgings for long. When the Titanic struck an iceberg at 11.40pm on 14 April, Charles helped his wife, daughter, and maid into a lifeboat – but tragically didn't manage to escape himself.

Charles, his son-in-law Thornton Davidson, and his secretary Vivian Payne were among the 805 male passengers who died that night. He's thought to have had a net worth of $565,000 at the time of his death, the equivalent of around $15.8 million (£12.4m) in today's money.

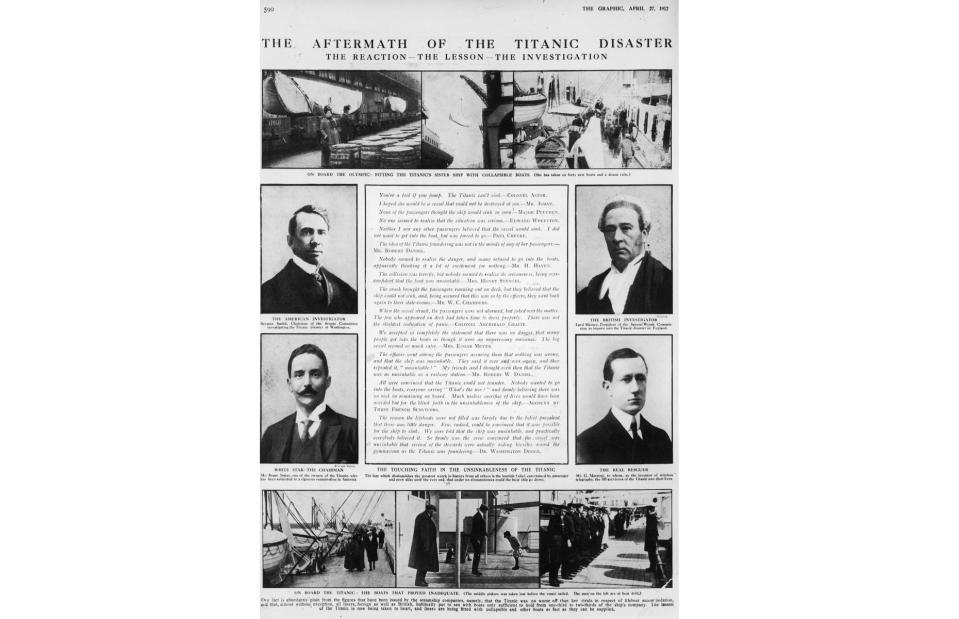

J. Bruce Ismay

Archive PL / Alamy Stock Photo

J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, inherited the business from his father Thomas when he was 36 years old. Thomas Ismay founded the shipping company in 1867 and remained at the helm until his death in 1899.

Keen to compete with the White Star Line's major rival, Cunard Line, Bruce wanted to build a fleet of large ocean liners. The result was three ships – the RMS Olympic, RMS Britannic, and RMS Titanic. When the Titanic set sail in April 1912, Bruce joined its maiden voyage to oversee operations.

J. Bruce Ismay

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On the night of the disaster, Bruce escaped aboard one of the ship's inflatable lifeboats, Collapsible C, about 20 minutes before the Titanic sank. It was a move that would haunt him for the rest of his life. As soon as he reached New York, Bruce was fiercely criticised for taking up one of the few spaces on a lifeboat when so many passengers – including women and children, who were supposed to have priority – had drowned.

To make matters worse, an inquiry revealed he'd reduced the number of lifeboats on both the Titanic and Olympic from 48 to 16. He'd also been overheard encouraging the captain to see how fast the ship could travel through the icy waters.

J. Bruce Ismay

Deeday-UK, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Bruce might have survived the Titanic but his reputation was in tatters. Although the British inquiry concluded he had helped as many passengers as possible before escaping on one of the last lifeboats, the public continued to vilify him, and he became increasingly withdrawn.

For the remainder of his life, Bruce worked for an insurance company that paid out money to the relatives of people who died during the disaster and donated $36,000 (the equivalent of over $575k/£451k today) to sea-related charities. He died in 1937 and is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London. At the time of his death his estate was worth $693,305, excluding property, the equivalent of more than $13.5 million (£10.6m) today.

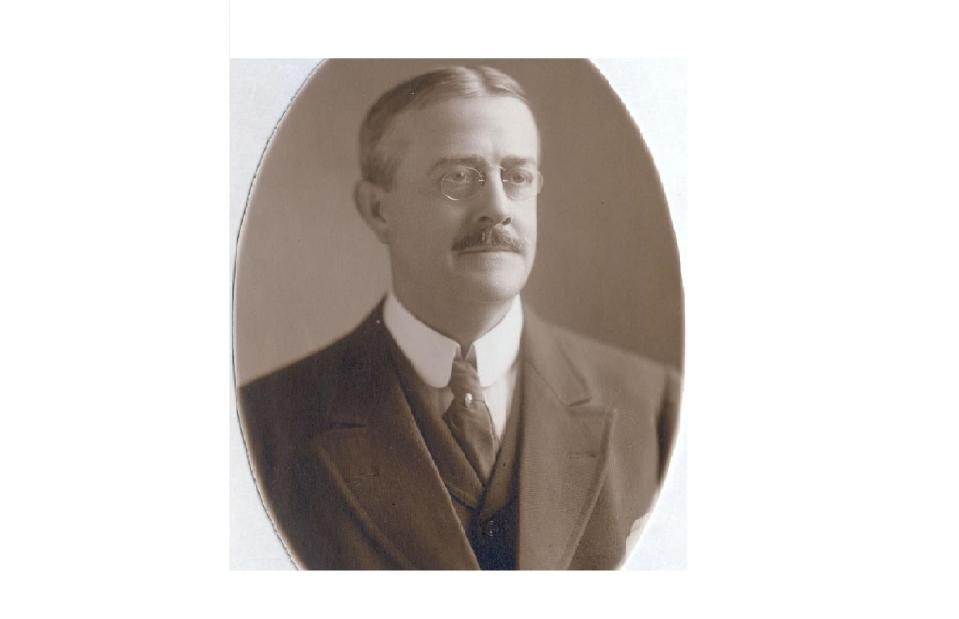

George Dennick Wick

http://www.mahoninghistory.org/Image071a-wick.htm, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

George Dennick Wick was born in Ohio in 1854. He founded the steel manufacturer Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company in 1900 with his business partner James Campbell and served as its first president. Poor health forced him to take a break from his duties, and in 1912 he embarked on a European tour in the hope of regaining his strength.

George Dennick Wick

Print Collector/Getty Images

George boarded the Titanic at Southampton with his wife and daughter, who were both called Mary. They were also joined by George's cousin Caroline Bonnell, and her aunt Elizabeth. According to a testimony from Caroline published in the Youngstown Daily Vindicator on 19 April 1912, George was last seen waving to his relatives as they were lowered into the lifeboats.

George Dennick Wick

Bettmann/Getty Images

All of his family managed to escape, but George wasn't so lucky. His body was never recovered after the disaster and he was officially declared lost at sea. To honour his memory, the Youngstown government organised a five-minute silence at 11am on 24 April 1912. The silence was observed in local schools, stores, and factories, including the Youngstown Steel and Tube Company (pictured).

It's reported that George had a fortune of $900,000 when he died, which works out at around $30 million (£23.5m) in today's money.

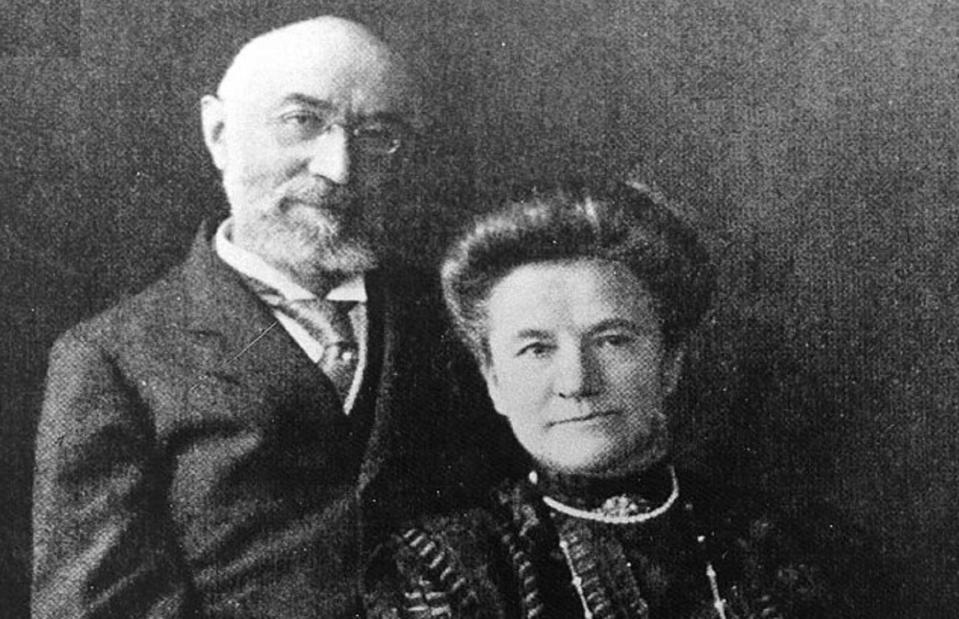

Isidor and Ida Straus

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Isidor and Ida Straus are the first people we've profiled who became millionaires during their lifetimes. According to a New York Times article published after their tragic deaths, the couple had a combined fortune of $3.8 million – the equivalent of around $110 million (£86m) today – thanks to their involvement with Macy's department store in New York.

With a background in crockery, Isidor had opened the glass and china department at Macy's. By 1896, he and his brother Nathan were the sole owners of the iconic store. Isidor also served a one-year stint as a US Congressman.

Isidor and Ida Straus

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Isidor and Ida were a devoted couple who would write to each other daily when Isidor was away on business. Towards the end of 1911 they went away together, spending the winter and early spring of 1912 in Europe. Some sources claim they were supposed to catch a different ship home, but coal strikes in England meant their original journey was cancelled. Instead, they booked two first-class tickets for the Titanic – a decision that proved fatal.

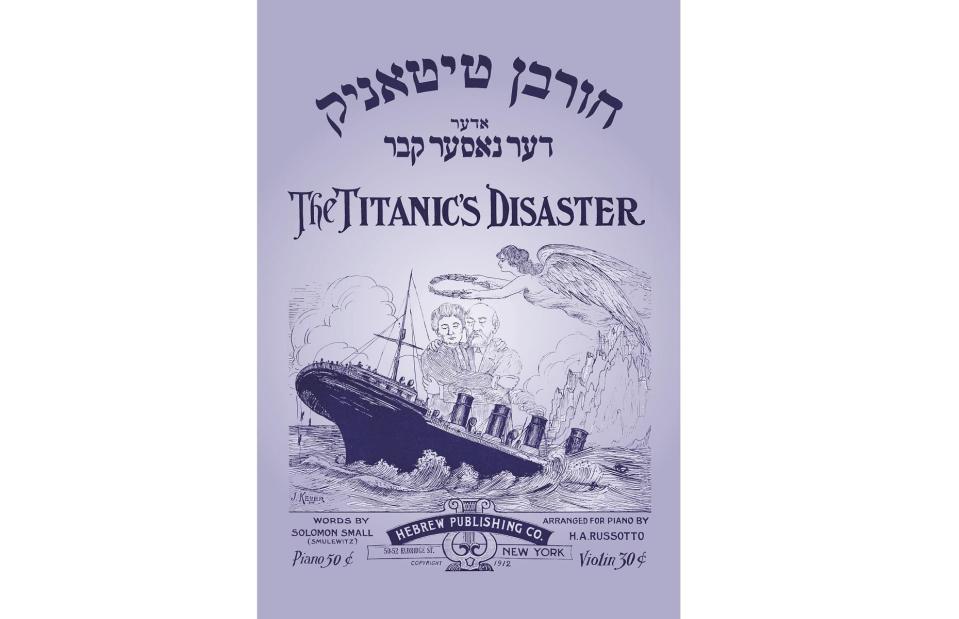

When the boat started to sink, Isidor refused to get into a lifeboat while women and children were still on board. Ida insisted on staying by his side, reportedly saying: "My place is with you". She gave her fur coat to Ellen Bird, her maid, and helped her into a lifeboat. The Straus couple then stood arm-in-arm on the deck until the ship went down, with their story inspiring a popular ballad entitled The Titanic's Disaster (songsheet pictured).

Isidor and Ida Straus

KMJKWhite, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Isidor's body was recovered and buried in the Straus family mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City. Because Ida was never found, the couple's children reportedly filled an urn with water from the site of the sinking and placed it next to Isidor in the mausoleum.

The couple's cenotaph features a quote from the Song of Solomon that reads: "Many waters cannot quench love – neither can the floods drown it". Pictured is a memorial plaque on the ground floor of Macy's.

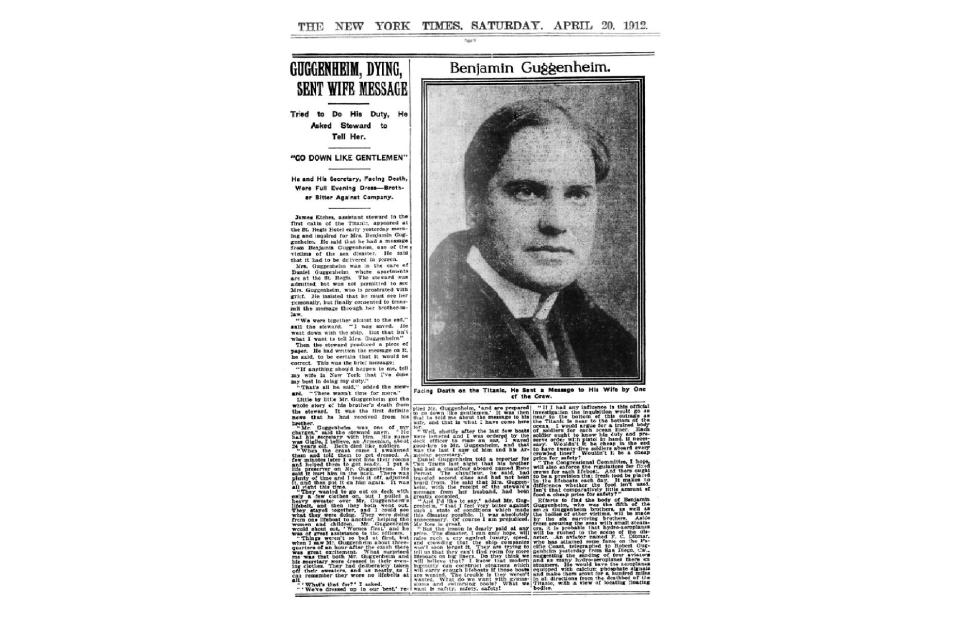

Benjamin Guggenheim

The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

With an estimated fortune of $4 million in 1912 (around $115m/£90m in today's money), Benjamin Guggenheim also enjoyed millionaire status during his lifetime. He was the son of a wealthy mining magnate who emigrated to America from Switzerland in 1847.

Benjamin soon joined the family business, earning the nickname "The Silver Prince" due to his interest in mining precious metals. He set sail on the Titanic when he was 46 years old.

Benjamin Guggenheim

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Benjamin boarded the ship with his mistress, a French singer called Léontine Aubart. Also in their party was Aubart's maid Emma, as well as Benjamin's valet Victor and chauffeur René. He was asleep when the Titanic struck the iceberg at 11.40pm and didn't wake up until after midnight.

Witness accounts claim he helped Léontine and Emma into the waiting lifeboats before returning to his cabin to change into his eveningwear. Once the last lifeboats had set sail, Benjamin was overheard saying: "We've dressed up in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen". Pictured is Benjamin's wife, Florette, waiting for news of her husband at the White Star Line offices in New York.

Benjamin Guggenheim

The New York Times (newspaper article, 1912), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin and Victor's bodies were never recovered. As a prominent businessman, Benjamin's fate was widely reported in the newspapers of the day. Speaking to The New York Times, his brother Daniel said: "I feel very bitter against such a state of conditions which made this disaster possible. It was absolutely unnecessary. Of course I am prejudiced. My loss is great."

George Dunton Widener

Yogi Black / Alamy Stock Photo

George Dunton Widener was the son of Peter Arrell Browne Widener, an American businessman who had interests in tobacco, cars, and oil. Peter outlived his son by three years, leaving behind a fortune of $35 million in 1915. In today's money that's around $800 million (£628m), so Peter's son George, who worked for the family business, was undoubtedly one of the richest passengers on the Titanic. The family's status was reflected in their opulent home, Lynnewood Hall in Pennsylvania, widely considered one of the greatest Gilded Age mansions in America.

George Dunton Widener

Courtesy St Paul's Elkins Park PA

George was travelling on the Titanic with his wife Eleanor and their son Harry. On the night of the disaster, the Wideners had dined with the ship's captain, Edward John Smith, before George and Harry retired to the smoking room. They were awake when the boat struck the iceberg and hurried to escort Eleanor and her maid onto Lifeboat #4. The men weren't so fortunate. Both George and Harry drowned and their bodies were never recovered.

Grief-stricken, the wealthy Wideners commissioned the designer Louis Comfort Tiffany, son of the founder of Tiffany & Co., to create commemorative stained glass windows for St Paul's Church in Elkins Park. Known as the "Tiffany windows", this picture shows a window created to remember Josephine Widener, George's mother.

George Dunton Widener

Heather Hacker/Shutterstock

Today, Lynnewood Hall is a shadow of its former self. The abandoned mansion has been empty since the 1950s, and in 2014 a restoration architect estimated it would take around $50 million (£39m) to restore it to its former glory. In 2023, it was purchased by the recently established Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation for $9 million (£7.1m).

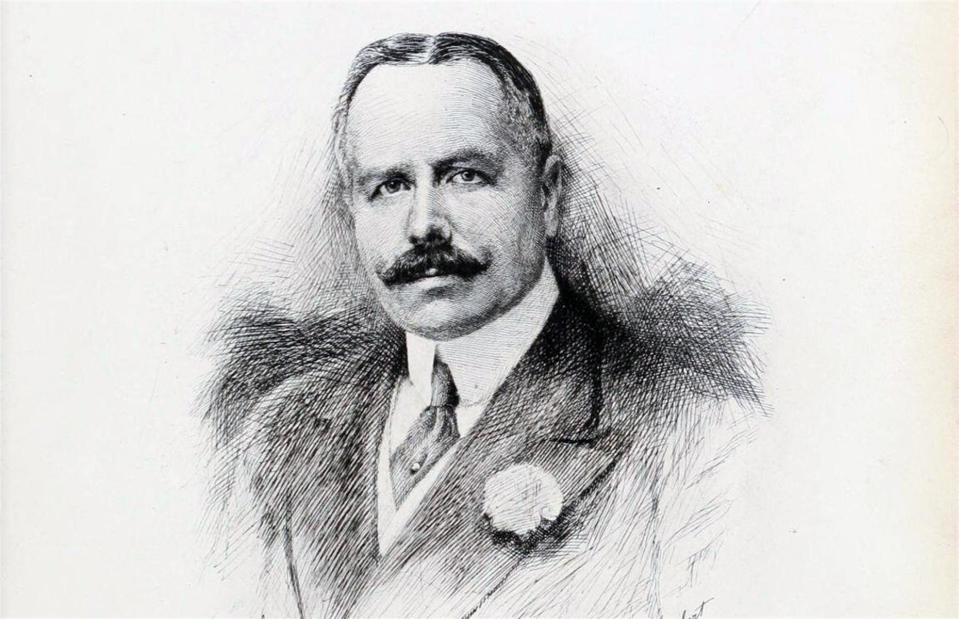

John Jacob Astor IV

IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

John Jacob Astor IV wasn't just the richest person on board the Titanic – he was also the richest person in America and one of the wealthiest men in the world. Born into the wealthy Astor family in Rhinebeck, New York in 1864, John enjoyed a privileged upbringing and entered the family real estate business as a young man.

He was also a keen writer and inventor: aged 30, he wrote a sci-fi novel set in the year 2000 called A Journey in Other Worlds, while his inventions included a bicycle brake and an early turbine engine.

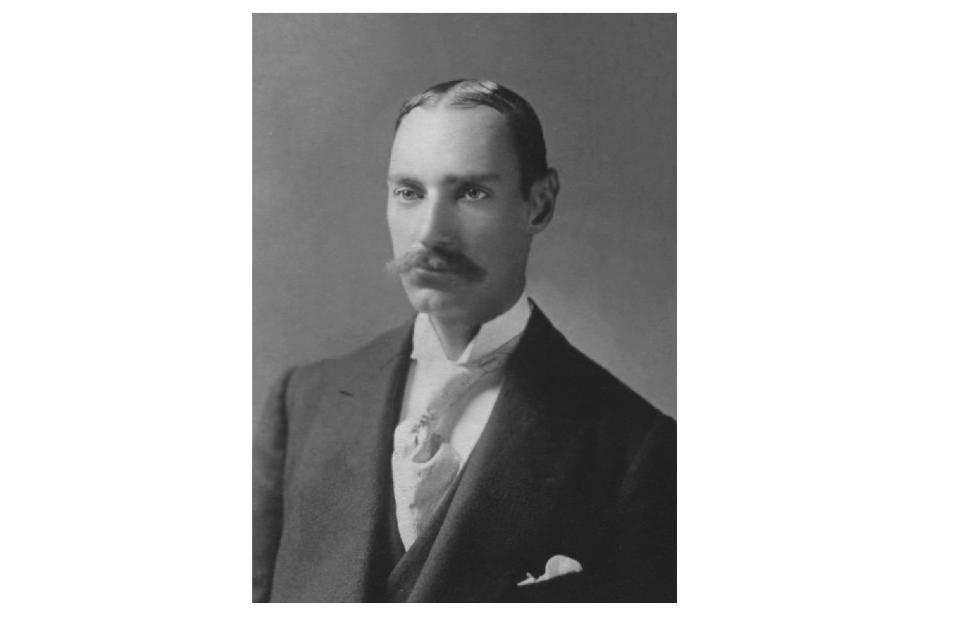

John Jacob Astor IV

Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

After divorcing his first wife, 47-year-old John married 18-year-old Madeleine Force in September 1911. The marriage attracted criticism due to the couple's 29-year age gap and the fact John had only recently divorced his first wife Ava. To escape the press, the Astors had an extended honeymoon in Egypt and Europe.

They left New York on the Titanic's sister ship, the RMS Olympic, and planned to sail home aboard the Titanic in April 1912. Madeleine was five months pregnant at the time of the disaster, and John asked if he could accompany her into the lifeboat to look after her. Officer Charles Lightoller, who became the last survivor rescued by the Carpathia, told him to wait until all the women and children had escaped first. John and Madeleine never saw each other again.

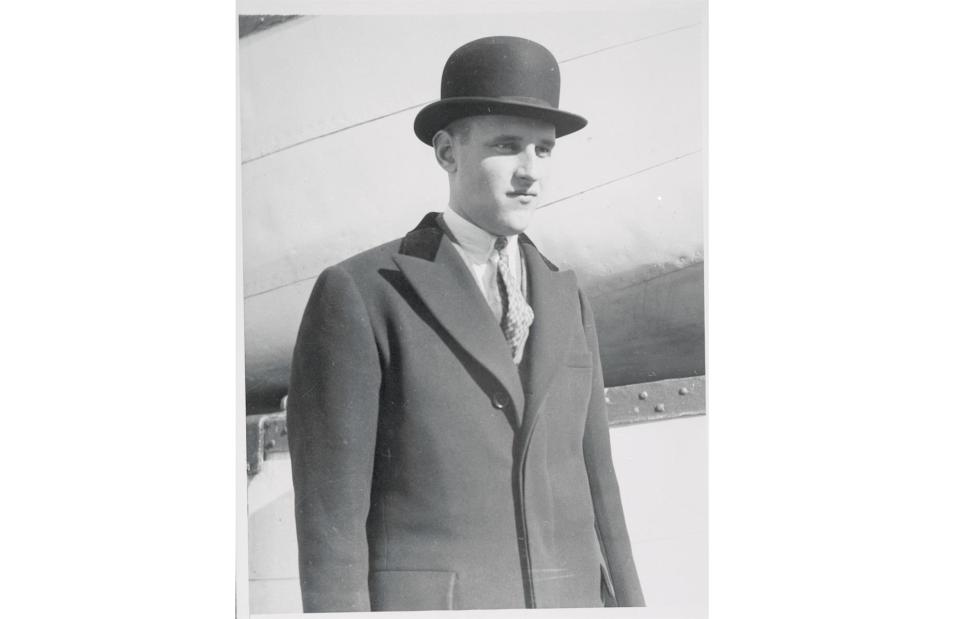

John Jacob Astor IV

Bettmann/Getty Images

When John's body was recovered from the water, he reportedly had $2,440 in cash in his pocket (over $70k/£55k in today's money). Madeleine gave birth to their son four months later and named him John Jacob after his father, although the boy was generally known by the nickname 'Jakey'. The press described him as "the Titanic baby" and, despite losing his father at sea, Jakey is pictured here aboard the SS Leviathan – a ship even larger than the Titanic.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance