Italy faces calls to come to terms with its dark wartime past 80 years after invasion of Yugoslavia

For decades, Italians liked to think that their soldiers behaved with decency and compassion during the Second World War, in contrast to the atrocities carried out by their German counterparts.

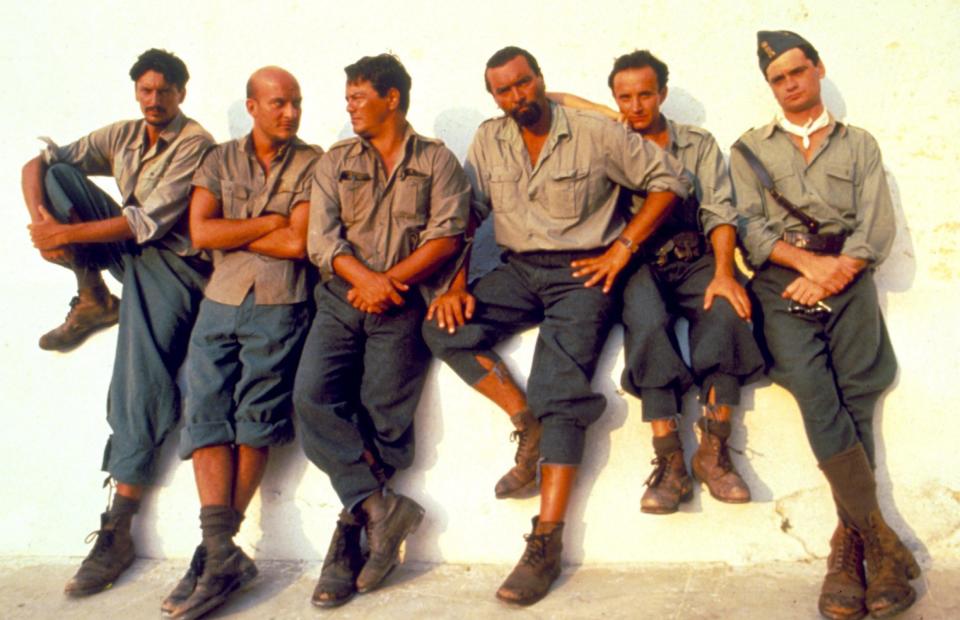

It was a comforting image that was perpetuated by popular culture, including the award-winning 1991 film Mediterraneo about a platoon of hapless soldiers stranded on a tiny Greek island who spend their days playing football with urchins, seducing the local women and swimming in the Aegean.

But it was a myth, the result of collective amnesia and wishful thinking.

Italy now faces an appeal to confront its past and to acknowledge that its troops massacred civilians, burned villages and executed prisoners during the war, in some cases on a par with the worst ravages of the Nazis.

A group of 140 Italian, Croatian and Slovenian academics and historians launched the appeal to mark the 80th anniversary of the invasion of Yugoslavia, which involved Italian, German and Hungarian forces.

They have written to Italy’s president, prime minister and its two chambers of parliament calling for a frank acknowledgment and condemnation of the atrocities perpetrated by Italian soldiers in Yugoslavia following the invasion of April 1941.

“To cancel out its defeat, and the fact that it had backed the wrong side in the war, Italy tried to build an image of itself as a victim of the war,” Eric Gobetti, one of the historians who organised the initiative, told The Telegraph.

The war crimes committed by Italians have been conveniently forgotten. “It’s the elephant in the room,” said Prof Gobetti.

“Italy underwent a collective psychological trauma that it has since tried to ignore. To this day, there is no memorial or record of the crimes carried out by Fascist forces in places like Yugoslavia. Nothing.”

Atrocities perpetrated by Italian forces are well documented but hardly known to the general public.

In the province of Ljubljana alone, in modern-day Slovenia, a thousand hostages were shot, 8,000 other Slovenes were killed, and 35,000 people were deported to concentration camps.

One Italian officer wrote at the time: “Everywhere you hear people saying that the Italians are even worse than the Germans.”

In contrast to Germany, which went through a painful coming to terms with its wartime past, Italy did not.

That was partly due to the exigencies of the Cold War period. “Italy was the weakest link in Western Europe – it was close to Communist countries and it had the strongest Communist party,” said Prof Gobetti.

Anxious not to make it any more unstable, the victorious Allies treated Italy leniently. Many Fascist officials remained in office. There was no Italian equivalent of the Nuremberg Trials.

The civil service could not be purged without destroying it – all public servants had been obliged to join the Fascist Party.

“The British and Americans, having made such a long and expensive effort to drive the Germans out of Italy, were not prepared to let the country go Communist,” said David Gilmour, a British historian and the author of The Pursuit of Italy.

“They were therefore unwilling to make the Italians feel too guilty about Fascism because this might have strengthened the PCI (Italian Communist Party).”

The call for a reckoning of past crimes coincides with a new online exhibition on the Italian occupation of Yugoslavia entitled “Put to the Torch – the Italian Occupation of Yugoslavia 1941-1943.”

“Other countries, like Germany, showed much more courage in coming to terms with their dark past,” said Raoul Pupo, the curator of the exhibition.

“We hope that finally, after 80 years, the right moment has arrived for Italy to do the same.”

Italian troops were part of a “vortex of violence” in Yugoslavia, Prof Pupo said. “They were not spectators but protagonists. It is one of the darkest pages of our history. But it is little known and people prefer to forget it,” he told Italy’s national news agency, Ansa.

Italy’s narrative of the war was also framed by the fact that it belatedly switched allegiance and ended up, albeit ambiguously, on the winning side.

Anti-fascist partisans were deified, even though there were not very many of them as a proportion of the overall population.

The fact that Nazis committed atrocities in Italy after the Armistice also enabled Italians to cast themselves collectively as victims.

The role of the partisans was “hugely exaggerated” after the war, giving the false impression that most of the country had turned against Mussolini’s legacy,” said Mr Gilmour.

As yet there has been no response from the Italian parliament or presidency to the appeal sent by the historians. “But it’s early days,” said Prof Gobetti. “We didn’t expect an immediate reply but we hope for a dialogue in the next few months. This is an unresolved trauma that prevents Italy from looking at its past honestly."

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance