How the James Bonds of the Past Might Reveal 007's Future

Just how much time does one need to die? Still more, it seems, as new Bond film No Time to Die has been pushed back yet again, to 8 October 2021. Originally slated for release on 2 April 2020, and now delayed for a third time, the 25th instalment in the near-60-year franchise has had almost as many stays of execution as 007 himself: “No, Mr Bond, I expect you to die – but later, elaborately, and briefed about my plan at length.”

But then timing is everything, and a global pandemic is an inopportune moment to release an expensively made film in cinemas, as evinced by the disappointing returns for Christopher Nolan’s time-warping Bond-alike Tenet. It remains to be seen – on 8 October, hopefully – whether No Time To Die’s deferments are purely about bums on seats, or also sensitivity about the plot. The trailer hints that Rami Malek’s villain Safin is bent on mass extermination via a mysterious “new technology”. Like a biological weapon? Maybe a virus? And his name is one letter away from deadly nerve gas “sarin”. Coincidence?

It was coincidence – luck – that the Bond film franchise launched in October 1962 with Dr No and its plot about missiles in the Caribbean, just weeks before the Cuban Missile Crisis very nearly blew up. (Studio United Artists had wanted to make Thunderball first but the story rights were legally knotty.) As recounted by John Cork and Bruce Scivally in 2002 book James Bond: The Legacy, communism seemed on course for global domination, with the Soviets winning the Cold War and the space race. The West was crying out for an “icon of its own values” – one who showcased the virtues of buying nice stuff.

Director Terence Young remarked that Dr No was “the most perfectly timed film ever made”. But that wasn’t just down to luck. The producers realised astutely that the zeitgeist was right for Bond, with the imperially diminished Britain instead leading the world in fashion, music, literature, architecture, design, art and film. And the scriptwriters cannily made Dr No work for SPECTRE, rather than for the Soviets, so the plot was less political. They also sexed Bond up from a one-woman-a-book man (on average) to a three-woman-a-film philanderer: a trebly-libidinous 007 for the liberal era of Playboy and the pill.

The Profumo affair, which saw a member of the British government caught in a Soviet honeytrap (Roger Moore eyebrow raise), erupted months before the October 1963 premiere of From Russia With Love. The book had been a favourite of the priapic JFK before his assassination in November by Lee Harvey Oswald, and both men had reportedly read Bond novels the night before the fateful event. That didn’t deter American cinema audiences, though, with reviewers hailing the film's “escapism”. The mania triggered by 1964’s Goldfinger, and other pop cultural happenings that year, was, write Cork and Scivally, “as if all the shock, rage and fear that had consumed society… needed to be released”.

The Bond films started taking much more inspiration from current events, and much less from Ian Fleming’s books, with 1967’s You Only Live Twice. Screenwriter Roald Dahl didn’t think his dearly departed friend’s story of Blofeld holed up in a Japanese castle with a “garden of death” was all that cinematic. So he came up with his own, about SPECTRE hijacking US and Soviet space capsules in order to trigger World War III and clear the way for its sponsor China, then feared as an emerging communist superpower (but apparently not such a concern in terms of global box office). The pre-credits sequence showing the death of an American astronaut cut adrift in space was filmed just over a fortnight before the Apollo I tragedy claimed the lives of three back on Earth.

For all their fantasticality, the Bond films have oft proved eerily prophetic. In 1966, a US plane crashed on the Spanish coast carrying four hydrogen bombs, weeks after the release of Thunderball. The satellite “laser” (Dr Evil air quotes) weapons of 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever were over a decade ahead of Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative or “Star Wars programme”. Hell, even 2002’s almost entirely ludicrous Die Another Day had pinpointed North Korea as a geopolitical hotspot before George W Bush located it in an “axis of evil”. (Despite that, Kim Jong Il was supposedly a big Bond film fan.)

Art can imitate life – and vice versa – too closely though. Critics felt the solar-powered plot of 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun, informed (partly) by the Arab embargo on oil shipments to the US in retaliation for arming Israel in the 1973 Ramadan War, was already old news. “The throbbing information that the ‘energy crisis is still with us’ isn’t what you need or want to learn from a James Bond picture,” sniffed the New York Times.

Roger Moore’s more overtly humorous tenure as Bond represented, by and large, a deliberate move away from the unrelenting grimness of current events, in particular a spate of bloody terrorism. Things got so bad that the Nobel Peace Prize wasn’t awarded in 1972, the year of the Watergate scandal, orchestrated by the SPECTRE-evoking CREEP (Committee to Re-Elect the President), which dimmed the public’s view of espionage.

Moore’s tongue-in-cheek characterisation meant the filmmakers could make 1973’s Live nd Let Die, based on an especially problematic Fleming novel that exploited racial paranoia in the US, and show Bond engaging in interracial sex without courting controversy, by capitalising on the blacksploitation genre and, for added comic relief, inserting a hapless redneck sheriff. For 1985’s A View to a Kill, they could film a politician being fatally gunned down in San Francisco City Hall, as Harvey Milk was years before, then set the building set on fire, with the blessing of public officials who gladly opened doors for them.

With the exception of 1981’s For Your Eyes Only, which pitched Bond back into the Cold War reignited by Reagan, Moore’s films were larger than life, and much more fun. And where 1985’s Rocky IV pulled no propagandic punches, 1983’s Octopussy could depict the risks of nukes and also not-nukes in Europe – a subject of ratcheting IRL tension – as well as Bond disguised as a clown, gorilla and crocodile. The villain wasn’t the whole “evil empire” but Steven Berkoff’s loose cannon (another eyebrow raise).

Telling good guys from bad became increasingly hard. But by putting a rogue Soviet general in league with an American arms dealer, the plot of 1987’s The Living Daylights, which prefigured the Iran-Contra scandal that broke during production, showed there were bad guys on both sides – and, because of the Aids epidemic, dialled down the dalliances of Dalton’s Bond. The subsequent collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union left Pierce Brosnan’s “relic of the Cold War”, as Judi Dench’s M dubbed him in 1995’s GoldenEye, not redundant but occupied with picking up the pieces. The US intelligence agencies who compiled the 2012 report on the global security threat posed by water shortages had presumably watched 2008’s Quantum of Solace, while 2015’s post-Snowden Spectre highlighted the perils of unchecked surveillance overseen by Moriarity.

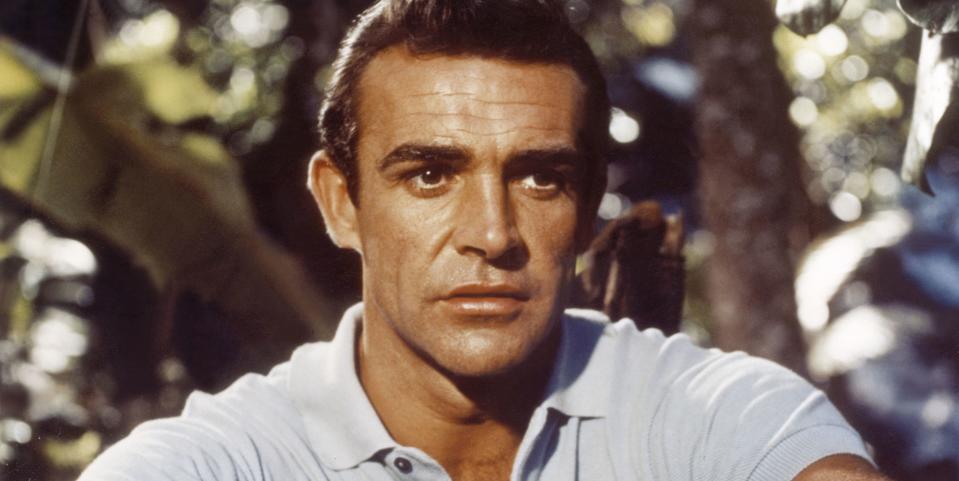

So, once the Craig era wraps up, what version of James Bond comes next? The filmmakers like to say that Bond exists “two minutes into the future”. But, given the unexpected turbulence of recent years, it’s hard right now to see even that far ahead. A shortage of bad guys and terrifying threats doesn’t seem like it will be a problem, though. Rather, Barbara Broccoli and co will be preoccupied with choosing the right ones, and deciding how Bond can convincingly respond. And respond he must – not just to save the world, but to divert it. Ever since Fleming first migrated from post-war Britain to Jamaica and started evoking exotic locales, escapism has always been part of Bond’s appeal. Connery knows, we need that more than ever.

Not just in the sense of what Kingsley Amis, in his 1965 treatise The James Bond Dossier, calls “magic-carpet excursions” either. All literature, however populist or profound, is escapist, implicitly assuring us that life is coherent and meaningful: “I can think of no more escapist notion than that.” Well, apart from SPECTRE being behind it all.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance