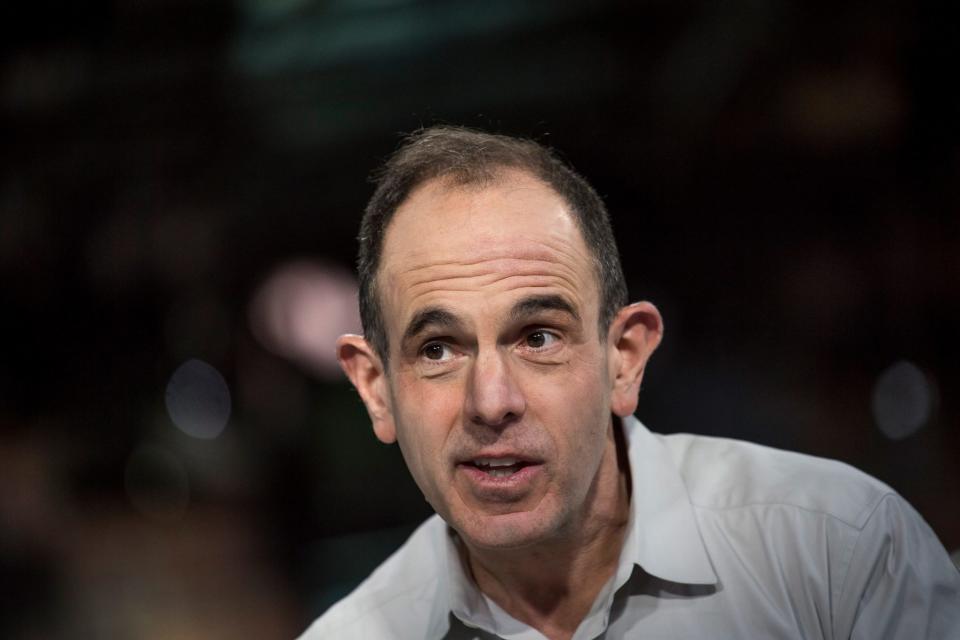

Keith Rabois on Miami, ‘pirate’ founders, and Stanford’s irrelevance to Silicon Valley

A VC’s job is to look at a company and simultaneously see what it is today and what it could be over time. We take for granted that VCs invest in startups and founders, but by the choices they make, VCs simultaneously invest in places—and no one seems to be more directly engaged with this than Keith Rabois, who’s thinking about his investment in Miami much like any other.

“When I first moved here, I thought it would take about ten years, which to an entrepreneur seems like an eternity, but from a venture perspective, ten years is the normal default,” Rabois told me over a Zoom call Friday. “In ten years, we want to have [in Miami] three or four really impressive, iconic companies.”

It seems like a goal that’s imposing—but just maybe doable. Rabois recently left Founders Fund to return to Khosla Ventures, a move he declines to discuss at length, saying it’s already “old news.” That may be true, but Khosla’s setting up a new Miami office in the trendy Wynwood neighborhood, a recognition of Rabois’ commitment to the city. Rabois moved to Miami in 2020, where he’s since cofounded e-commerce aggregator OpenStore and invested in Miami-based startups like Traba, which has raised $43.6 million to date. He will now be Khosla’s first partner based in The 305.

Rabois going all-in on Miami has been well-covered, albeit with an air of quirky skepticism. And I get it—after all, Miami is known for its nightclubs, South Beach, and proximity to the Caribbean.

But I come to Rabois’ argument for Miami with a different skepticism: I grew up in Miami. When I left for college, I figured I would never come back (and haven’t) for lack of professional opportunities. I tell Rabois this, and dare him to persuade me otherwise.

He outlines a case for Miami that’s both data-oriented and historic. Rabois cites third-party studies (like this one conducted by Mindbody) that call Miami America’s happiest city. “Entrepreneurs are humans too, and entrepreneurs want to be happy and healthy,” he says.

“The only ingredient missing is capital—angel capital, not just venture capital and institutional capital, and it turns out that’s basically the history of Silicon Valley,” Rabois added. “ [Sand Hill Road is] the most mundane, boring, drab place on the planet, but it became a thing because there was a colocation of investors back then, mostly angels or pseudo-angels with an unusual risk appetite…[entrepreneurs] came to meet the capital.”

I push back: What about Stanford? Didn’t it play a key role in Silicon Valley’s development? Rabois may have gotten his BA at Stanford, but his response is stark and quintessentially contrarian.

"I don't think Stanford's relevant in the history of Silicon Valley at all,” he told me. “The companies that are important to the history of Silicon Valley weren’t founded by Stanford undergrads.”

He and I run down the list of Silicon Valley’s most important companies, past and present—no to Apple, Facebook, Netscape, and Salesforce. Google also doesn’t count, since it was “Stanford grad students, not undergrads,” Rabois distinguishes. (It didn’t occur to me until later to ask him about Palantir, a company cofounded by Joe Lonsdale and Rabois’ longtime associate Peter Thiel, both of whom were Stanford undergrads.) It’s an animated argument that he says he picked up from Sebastian Mallaby’s 2022 book, The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future. It’s also an argument that affects who he writes checks to—Rabois said doesn’t even particularly like funding entrepreneurs from Stanford.

"Stanford grads are like the Navy and you need pirates,” he told me.

Talking to Rabois, he’s persuasive and systematic in how he articulates himself. In a lawyerly way, he’s able to build a case using facts the way bricks build a wall. (I remember later that he is, in fact, a lawyer.)

Rabois is methodical, and it’s a trait that seems to apply across the board. We get to talking about his well-documented love for Barry’s Bootcamp, and though he enjoys telling me the story of how he got into the high-intensity interval training workout (it’s a tale that involves Instagram cofounder Kevin Systrom and Spanish wine), he’s having the most fun delineating exactly why Barry’s is such a good product.

Rabois loves Barry’s for the workout’s efficiency, efficacy, and musicality. He knows exactly how many classes he’s taken and how many he’s taught. (He’s careful to tell me he’s only taught 16 classes.) We talk about types of Barry’s instructors—some are drill sergeants, others are encouragers.

I ask Rabois which type of instructor he gravitates toward. We both realize I already know the answer.

"I like to crack the whip, probably not surprising.”

See you tomorrow,

Allie Garfinkle

Twitter: @agarfinks

Email: alexandra.garfinkle@fortune.com

Submit a deal for the Term Sheet newsletter here.

Joe Abrams curated the deals section of today's newsletter.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance