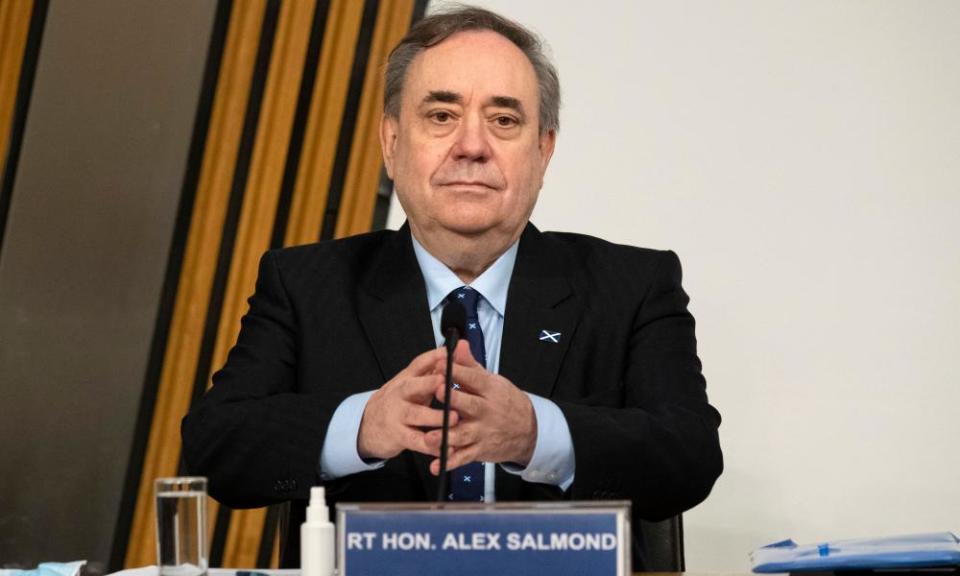

What we learned from Alex Salmond's evidence to Scottish parliament's inquiry

What questions does Alex Salmond’s evidence raise for Nicola Sturgeon?

The former first minister said that he could provide witnesses to confirm his version of two key points in the saga, and which Sturgeon has given competing accounts of, to bolster his assertion that there is “no doubt” she broke the ministerial code.

During a lengthy and detailed evidence session, Salmond claimed that the head of the civil service, Leslie Evans, met a complainer and spoke to the second one on the phone while they were taking the allegations forward, in what he described as a “spectacular” breach of process and which the Scottish government failed to disclose to the police despite a warrant.

Under questioning by the acting leader of the Scottish Labour party, Jackie Baillie, Salmond agreed that if Sturgeon had continued to defend the judicial review brought by him into the handling of the original complaints, despite knowing about these prior contacts, she would have broken the ministerial code.

Related: Salmond v Sturgeon is not just a battle of personalities | Ruth Wishart

She will also probably be questioned on when she knew about the allegations: Sturgeon previously told the Holyrood chamber she first heard about the allegations at a meeting with Salmond at her home on 2 April 2018. It has since emerged that she was told about them by his former chief of staff, Geoff Aberdein, in her office a few days before on 29 March, a meeting Sturgeon has said she had forgotten about, describing it as “fleeting”.

But in his evidence, Salmond insisted that the meeting was not “impromptu”, but pre-arranged, stating: “The purpose of the meeting was to brief Nicola on what was happening. I know that Nicola Sturgeon knew about the complaints process on 29 March.”

Related: Alex Salmond: weak leadership could hurt case for Scottish independence

Salmond also alleged that Sturgeon left him “in no doubt” that she was going to intervene in the complaints process, and that this was “perfectly proper” as it related to the potential for mediation between parties. Sturgeon has previously denied this, but Salmond said that his lawyer Duncan Hamilton was in the room at the time and heard the offer.

Sturgeon may also be pressed on why, as she has previously stated, she met Salmond because she thought he was about to resign from the party: he told the committee on Friday that resignation from the SNP “never entered my head”. He also raised the question of whether the meeting was party or government business, another potential breach of the ministerial code.

Was Salmond’s team told the name of a woman who made one of the initial sexual harassment complaints against him?

Under questioning from Baillie, Salmond said the name of a complainer was shared with his former chief of staff while he was setting up the meeting between Salmond and Sturgeon, and that “three other people know that to be true”. Bailie said that the committee had already written to them to establish this.

Asked about this allegation at first minister’s questions on Thursday, Sturgeon said: “To the very best of my knowledge I do not think that happened.”

What evidence did Salmond offer to support his claims of a “malicious plan” to destroy his reputation?

Replying to a question from the independent MSP Andy Wightman, Salmond offered a number of key points to back this up. These included the timing of the decision to extend the new harassment policy to include former ministers and switching the key decision maker in the policy from the current first minister to the permanent secretary. They also included “shocking” text messages between senior party and government officials, which Salmond claims indicate that witnesses and the police were pressurised to pursue his criminal charges in order to overtake the judicial review, which the government had been warned it would lose. But he also confirmed that he had no documentary evidence that suggests Sturgeon was involved.

Did Salmond address his own behaviour in his evidence?

From the outset of his long-awaited evidence, Salmond underlined that the committee’s remit was to investigate the Scottish government’s handling of sexual harassment allegations made against him, rather than his own conduct: “This is not about me.”

Earlier this week, Nicola Sturgeon accused Salmond of making “wild, untrue and baseless claims” about a conspiracy against him, to divert attention from questions about his past conduct.

Related: What is the Alex Salmond controversy all about?

Salmond described the past three years as a “nightmare”. Since the verdicts, the female complainants have themselves been subject to relentless abuse and exposure online. On Thursday, a man was jailed for six months for breaking the court order protecting their anonymity by tweeting their names.

Inquiry member Alex Cole Hamilton, who was rebuked for his questioning by the committee chair, noted that Salmond had not mentioned the women involved in bringing the complaints in his opening statement and asked Salmond directly: “Of the behaviours that you have admitted to, some of which are appalling, are you sorry?” Salmond said in his own evidence at trial that he should have been “more careful with people’s personal space”, while civil servants told the court they tried to reinforce the practice of not allowing female officials to work alone with him.

Salmond responded: “In my statement I pointed out the government’s illegality has had huge consequences for a number of people, and specifically mentioned the complainants” but refused to address them directly: “I’ve had three years of two court cases, two judges and one jury and I’m not going to be drawn further on that.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance