‘The Mark Duggan case was a catalyst’: the 2011 UK riots 10 years on

On 4 August 2011, Mark Duggan was shot and killed by police in Tottenham, north London, sparking the largest civil unrest the UK has seen for a generation. The disturbance quickly spread and for five nights, London, Birmingham, and other major cities in England were engulfed by fire and violence.

On the 10th anniversary of the riot, community leaders and frontline workers reflect on what they witnessed and the impact of those nights.

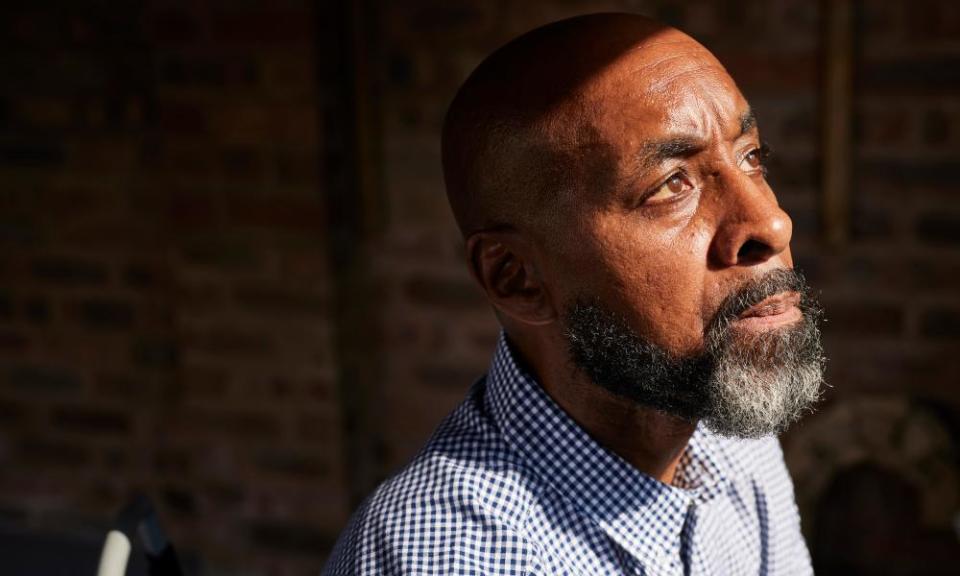

Stafford Scott, a community organiser who was at a gathering led by Duggan’s family

There was a gathering of about 40 people, mainly young women, because it was led by the mother of Mark Duggan’s children, Simone Wilson. We went along to a police station and expected the police to have anticipated our arrival. We sent messages to them. When we got to the station, we agreed among ourselves that the women should go inside because we didn’t want the police to feel threatened. The police said that they couldn’t speak to them, because the IPCC was investigating the matter, but that was totally incorrect.

When the women left, the police came out and drew down the shutters. That really sent the most negative of signals to those who were outside. People started to use social media to tell others about the disrespect shown to the Duggan family over the last couple of days, how his parents were waiting to hear official confirmation of what they were seeing on the media [that Mark had been killed]. As the day wore on, it just built up and built up and built up. Had the police dealt with the small group that had originally turned up, we wouldn’t even be talking today. (In February 2012 the police and the IPCC were forced to publicly apologise to the Duggan family and acknowledged it was their responsibility to deliver the death message).

I understood the young people’s frustration. I absolutely understood it. But I didn’t understand why they decided to loot. I was on Broadwater Farm in 1985. There was no looting whatsoever. The young people, myself included, took anger on those who created the anger, the police. But in 2011 too many young people lost their minds, then it was an uprising.

My mum lives in Tottenham, Bruce Grove. She had to go miles as a pensioner, to buy bread, miles to get her pension from the Post Office. So it really tore me up to see Tottenham burning like that.

There are similarities to 1985. In 1985, we tried to leave the estate to protest at the station and they wouldn’t allow us. The feeling was the same; that we were being denied our right to be heard. And we know what Martin Luther King says, about voiceless people; riots are the language of the voiceless.

On the 10th anniversary, we’re going to be at the ICA in the Mall [at the War Inna Babylon exhibition]. We’ve taken the frontlines in the fight against racism off the estates, from out of the hood and we’re bringing it uptown.

Rev Betsy Blatchley, former vicar of St Luke’s Hackney

We were aware of what had happened in Tottenham. There were around six shops that were starting to close and there was this real sense that something was going to happen in Hackney. I’d walked down to meet Rob Wickham, who was then the vicar of St John’s Hackney, the big parish church in the centre. And he said I think we should walk down towards Mare Street just to have a look at what’s going on.

It then became clear that there was now a real confrontation between the police and a lot of the young people. We walked around trying to calm things down as much as possible.

When I came back that evening, there was a car set on fire and shop that was completely looted and wrecked. The next day, there was still a lot of anxiety, tension and unrest. Talking to one fairly well-educated and well-off anarchist, I felt there was a degree of stirring things up as well. The police said all we could do was hold our line and hope for the best.

There was a comment from David Cameron that it was criminality pure and simple. And I thought, it’s not simple at all, it’s very complex. I think people got involved for a lot of different reasons. I can never condone any sort of violence or damage to property, but I think the anger and frustration came out of a lot of different things, with the Mark Duggan case a catalyst. A lot of young people who, rightly or wrongly, felt aggrieved and in some cases left behind.

There was one young man who was a member of my congregation who wasn’t involved in Hackney, but he had just received some very bad personal news and he admitted to kicking a window in. He was accused of stealing but he always maintained he didn’t. I wrote a quick character reference for him and he was sentenced to three months. I went to visit him in a young people’s unit, and he was so hopeful and he really tried to turn things around and do everything right, but I just thought this was a young black British man who now had a criminal record and how that was going to affect his life.

Derrick Campbell, former government adviser on violent crime

When the riots happened, I was one of the people advising then prime minister David Cameron. We were trying our best to put the genie back in the bottle. I did a lot of press interviews – about 27 interviews in one day – lots of stakeholder engagement, and lots of talking to the heads of gangs. While we had mass public disorder spreading across the country, the rioting and looting, there were also some very sinister things going on.

I wasn’t at home, I spent most of my days meeting people from the crime fraternity and other community leaders from the churches, the mosques and gurdwara’s, to work with them and create a collective approach as civic leaders to ‘turn this thing off’. I was very critical of the establishment, such as the local authorities, who in my view basically hid behind barricades and just let their cities burn. And the media who I felt were very poor and culpable of exacerbating the disturbance. They wanted to have something to talk about.

At the time, young people felt they were subjected to unacceptable levels of overpolicing and there was a sense of disfranchisement. The shooting of Mark Duggan was said to be the reason for the disturbances but that wasn’t the case, it was simply the spark. We were working for years within the community and many felt abandoned and forgotten by the establishment. Long story short, society was broken.

So all of that underground frustration, coupled with the fact that the young people felt a sense of injustice and reduced opportunities, all of those things together created the perfect storm. We also knew there were people who saw an opportunity and were deliberately agitating the water. They mobilised their networks, which were strategically placed in different parts of the country, and created the rapid spread of disorder. I don’t think you could replicate that again.

I remember one of the biggest complaints from the Wolverhampton community was that the police didn’t do anything to protect their businesses, because the police thought it was better to protect the new multimillion pound bus station. So all the shopkeepers had to take it into their own hands to protect their shops. That caused even more anger at the police.

Related: A decade after Tottenham burned, social alienation means riots could happen again | David Lammy

Many lives were ruined by it, because you had young people who had never been involved in crime before, who simply got caught up in the moment, and they are now paying a heavy price for that.

Sami Goldbrom, station commander at London fire brigade in Tottenham

At the time, I was a junior officer at Islington fire station. I was in the office about 10 o’clock, making a cup of tea and I saw on BBC News a burning building and riots. I thought where is that? Then saw it was in Tottenham, and our lights came on, the bells went down and we were sent to a holding station.

En route to a fire call we drove down Green Lanes in Haringey, where there are 24-hour Turkish fruit and vegetable shops. There were loads of the guys who worked at the shop standing there with baseball bats [to protect their assets].

Right behind the shopping centre, there was a burning car. We got off and started putting the car out. I asked my driver to send a message that we didn’t need any further fire engines as I thought that would be the end of it really. He said: “Sam, have you seen that shop over there is alight?” And my heart sank. There was tension in the air and a lot of people running around. It became very obvious that we were right in the middle of civil disturbance.

There was mass looting going on. Kids were taking wheelie bins out of people’s front gardens, running them up to the Carphone Warehouse and throwing stock in. I couldn’t just walk away from that because above Wood Green shopping centre is a housing estate, with about 500 houses and flats. So I put in an urgent assistance call to control. It was four of us dealing with a fire which needed probably 16-20 people. The cavalry did eventually turn up.

I’m from the area and as a kid I was always kicking around Wood Green. What I saw those kids doing was a sign of the times. I know that the London fire brigade had been doing community work and certainly in my time as the station commander at Tottenham, we’ve done loads of community intervention locally.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance