Max Clifford: The Fall of a Tabloid King review – scandal at the heart of Fleet Street

There appears to be no reason for the documentary Max Clifford: The Fall of a Tabloid King (Channel 4) – there is no anniversary of his arrest, charge or conviction on eight counts of indecent assault against four victims, or of his death three years into serving his eight-year sentence. However, we do not live in an age when a documentary about the symbiotic relationship between celebrity, handler-slash-story-supplier and media editors, or the ways in which a man in a position of power and influence used it to exploit young women and children, can ever be called untimely.

Rather, we’re at a point where the latter story, especially, has become almost too common to merit comment. The greatest question such retrospective anatomisations used to try to answer was: “How did they get away with it for so long?” Now, the one that looms most unavoidably with every fresh story – about an apparently cuddly TV presenter, popular light entertainer, R&B star, Olympic sports coach and so on – is: do men seek power and influence for any other reason than to abuse it? We’re getting to the point, surely, where it’s better and safer to move forward on the accepted basis that anyone rich and famous has become so because they need the protective trappings that come with it – including a large network of enablers and/or people cowed into silence – in order to satisfy the kind of desires that would otherwise quickly get them arrested.

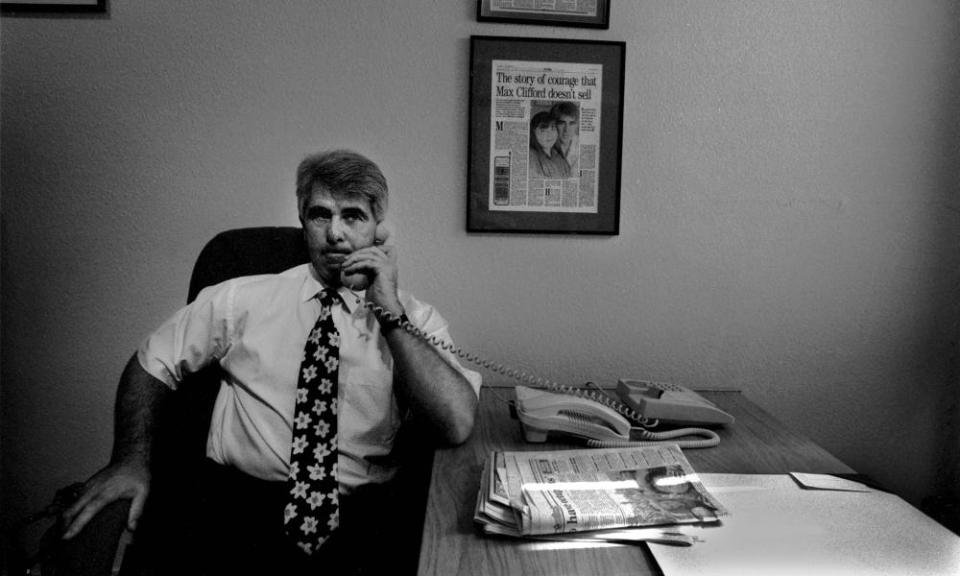

But whether power always corrupts (or the corrupt always secure power) is a different – deeper and darker – question than documentaries like this one, devoted to a single figure treated as an anomaly, pose. The first half was dedicated to Clifford’s rise as a publicist, supplying exclusives that could net a paper an extra 100,000 sales a day, until he eventually sat like a spider at the heart of the tabloid web, throwing out threads of story here, binding and biting the necks of paralysed victims there. In a lockdown-friendly format, talking heads are interviewed singly, their insights interspersed with clips of the plentiful footage of Clifford and his clients from the decades that he was the nonpareil supplier of celebrity stories and scandals to Fleet Street.

As the film worked its way through the “Freddie Starr ate my hamster” and David Mellor/Antonia de Sancha years, it also covered the barely concealed sex parties Clifford held, involving young women whose enthusiasm he always proclaimed was genuine and unbounded. They – or at least the ones who spoke to Mail on Sunday investigator Nick Fielding for a piece he started putting together in the 1990s to clip Clifford’s wings – recalled it differently. Clifford was a keen voyeur and had compromising photographs of many unwitting individuals who crossed his path taken from hidden vantage points. It all helped. Fielding’s piece never made it to print. He never found out why.

So much footage of Clifford’s greatest hits was played, as former editors lined up to attest – heads shaking in wonderment – to Clifford’s talent for stories, showmanship and shifting units. At these moments, the programme skirted perilously close to, if not hagiography, then at least glamorisation of how far and how fast you can go as a man without conscience.

The programme was saved by interviews with the women who eventually testified against Clifford at trial. Foremost was “Kate”, whom Clifford had groomed since he met her when she was 15, blackmailing her into continuing their sexual relationship when she tried to detach from him. After she came forward, so did many, many other women, from all over the country, independent witnesses corroborating each others’ accounts of Clifford’s tricks, methods and lies.

Related: Max Clifford obituary

The Fall of a Tabloid King remained, overall, an essentially superficial look at a profound problem. It hinted occasionally at the greater depths (most notably when it asked Neil Wallis, former deputy editor both of the Sun and the News of the World, if he thought Fleet Street was complicit in Clifford’s success as a serial abuser. He could muster no more after a long, long pause than: “It’s just complicated”), but didn’t plumb them. But because we are so familiar now with the story and the pattern of predators, producers need to dive deeper to avoid effectively fetishising them (as they have always done with serial killers). We, and above all, their victims, deserve better. Better questions, and better answers.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance