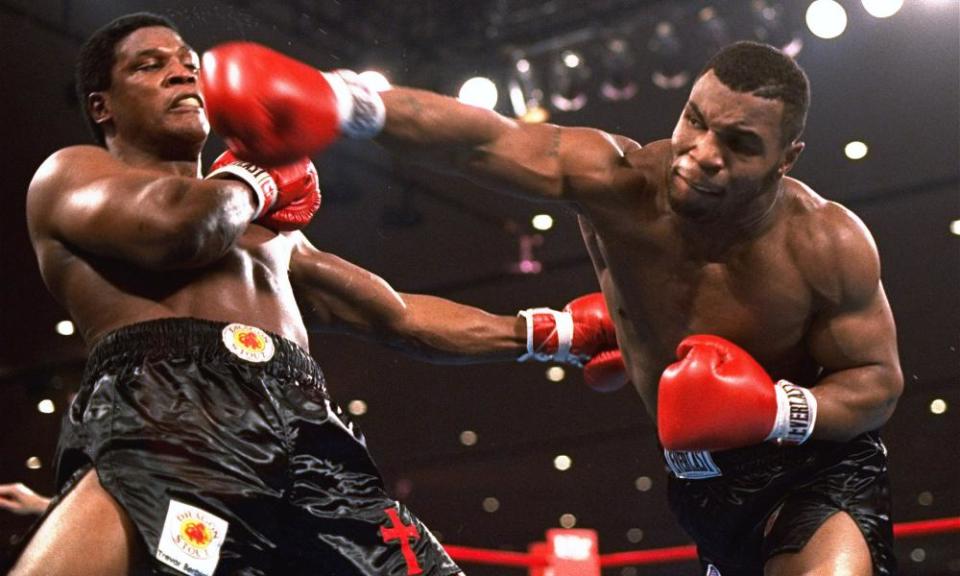

Mike Tyson's dangerous comeback is painful reminder of Liston's tragic tale

No one knows boxing history like Mike Tyson. He made plenty of it himself during 20 years as the most feared heavyweight in the world. But there are a lot of things he doesn’t know, and the consequence of his ill‑advised comeback is one of them.

Tyson, 54, has not fought since Kevin McBride, a modest Irish heavyweight with much to be modest about, made him quit on his stool after six rounds on the undercard of a show in Washington DC, in June 2005. Like most champions, he quit too late, but what a ride it was.

Five years before the McBride fight, Tyson went to Glasgow and knocked out the normally steadfast American, Lou Savarese, in 38 seconds. Fans who had flocked from all parts hoping to get a prolonged look at the fading ogre that June evening at Hampden Park were not best pleased. It was the 22nd first-round win of Tyson’s career. His post-fight rant lasted nearly as long as the fisticuffs.

Related: Mike Tyson's crazy comeback talk is the perfect lockdown story | Barney Ronay

“I’m the best ever,” he said. “I’m the most brutal and vicious, the most ruthless champion there has ever been. There’s no one can stop me. Lennox Lewis is a conqueror? No! I’m Alexander. He’s no Alexander. I’m the best ever. There’s never been anyone as ruthless. I’m Sonny Liston. I’m Jack Dempsey. There’s no one like me. I’m from their cloth. There is no one who can match me. My style is impetuous, my defence is impregnable, and I’m just ferocious. I want your heart! I want to eat his children! Praise be to Allah!”

Iron Mike is much quieter now. The days of terrorising his sport as well as every bar from Los Angeles to New York are memories, good and bad. He might look fit for a retired athlete, but that is all he is now, a middle-aged man with a beard.

However, on 12 September at the Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, California – where David Beckham played football for LA Galaxy – Tyson will go through the motions with Roy Jones, another shadow of a champion, albeit a great one, in an eight-rounder the promoters are sensible enough to call an exhibition.

What dignity there is in the park, meanwhile, will be determined by the combatants’ willingness to take part in the sham. If it were for real, it is hard to say who would suffer most. As it is, they both lose.

Jones, who is 51 and has the decency not to call himself Junior any more, last fought in 2018. It could be argued he has more right to be there, but it is a line call. Nevertheless, it is Tyson who is the draw. He always was, even when he was washed up.

Seven years ago, hovering on the brink of despair, he admitted he was, “a vicious alcoholic” with no future, only a bad past. “I’ll never be happy. I believe I’ll die alone. I’ve been a loner all my life with my secrets and my pain.” Just like Liston, the fighter with whom he has most empathy.

On 5 January 1971, when Mike was a kid living in a cold, damp flat in Brownsville, New York, Liston was discovered lying dead and alone, draped across his bed like a kayoed fighter, in a ramshackle house in one of the poorer parts of Las Vegas. Not your usual role model.

They never met, of course. Tyson was four when Liston had his last fight, a surprise win against Chuck Wepner that many say wasn’t supposed to happen. Liston’s death six months later gave strength to the rumours that he had double-crossed the mob by refusing to take a dive. But even the excellent new documentary, Pariah: The Lives And Deaths of Sonny Liston, could reach no definitive conclusion.

Liston’s whole life was a mystery. He wasn’t sure himself exactly when or where he was born – although it was definitely in rural Arkansas, probably some time in 1930. Nor could the coroner say exactly when he died. As Liston’s chronicler, Nick Tosches, wrote: “Only he and the men who killed him knew the date of his death.”

Someone once said of Liston: “He died the day he was born.” Tyson had more chances than Liston had to beat Damon Runyon’s odds on life – 6-5 against – but it has been a struggle.

By his own admission, Tyson’s life has been a rolling mess – taking in enormous wealth, bankruptcy, three marriages, seven children and one jail term for rape – but it has improved, on and off, since he walked away from boxing. It has not been easy. He lent his name to a best-selling autobiography, he has been in movies and … he endorsed Donald Trump. So, a mixed bag.

In Pariah, Tyson describes Liston as “the first intimidating fighter, with the mean scowl and the mean grin. He was a real badass, menacing boy”.

So was Tyson, even more so. Before he dined on Evander Holyfield’s ears in 1997, only a handful of his opponents had made it to the second round – most notably Buster Douglas, who knocked him out in Japan seven years earlier.

By then the aura, his third fist, was ebbing away. There were shreds of it left when he came out of prison in 1995 and terrified Peter McNeeley for a minute and a half. He would do the same to Frank Bruno seven months later to get his title back and retire the troubled British fighter. From there to the end he won a few contests, but Tyson was a sitting duck for anyone with ambition and a good chin.

Liston said many wise things in his 40 or so years, the most poignant quoted at the beginning of Pariah: “Ever since I came into this world … I’ve been fighting to stay alive and live a reasonably normal life. I’ve never been able to do it.”

The sadness of Mike Tyson is that he knows his history. He knows what happened to Sonny. Yet, even though he has tasted normality, even though he has survived his many nightmares, he is drawn again to the danger of a trade in which normality is not even a second-class citizen.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance