Moses Fleetwood Walker: editor, author and major league baseball's first black star

Second-degree murder was the charge that they gave him, and his win probability did not look good. For one thing this was the 90s – the 1890s – and he was Black in Syracuse, New York. For another the man he killed was white. It hardly mattered that this man – some yob named Patrick “Curly” Murray, a cousin of the local alderman – came looking for trouble with a group of white men outside a bar, and struck first with a rock. A knife to the stomach had extinguished Murray in the prime of life, and the job of apportioning blame had fallen to an all-white jury. Surely, they’d throw the book at Moses Fleetwood Walker. But as luck would have it, he was a helluva catcher.

Related: MLB corrects 'clear error' and reclassifies Negro Leagues as a major league

Before Jackie Robinson dared to cross baseball’s color line in the spring of 1947, there was Moses Fleetwood Walker – the pioneer that time always forgets. Though he is technically the second Black player to play in the major leagues after William Edward White was called up for one game in 1879, because White was biracial and passed himself off as a white man, Walker – mixed race too but unapologetically Black – was the first to endure vitriol and threats of violence from fans and players alike.

The son of a Black physician, Walker was born on 7 October 1856 in the eastern Ohio village of Mount Pleasant. The Society for American Baseball Research has him taking up the national pastime in his youth, after a family move up-river to the industrial town of Steubenville. Records of his play don’t begin to emerge until the late 1870s, as a 20-year-old Walker asserted himself as a catcher and leadoff hitter on the prep team at Oberlin College. Baseball was still an interclass game when the college opened play on a new field in 1880, and Walker punctuated the occasion with a grand slam. The next year Walker anchored Oberlin’s first intercollegiate varsity team and capped the season with a blowout of the University of Michigan that ended with a transfer offer from the Wolverines, which he accepted.

Just before his move to Ann Arbor, though, Walker took a sweet semi-pro gig in August 1881 with the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland. The game was in Louisville, Kentucky, against an outfit called Eclipse – a future charter of the American Association, an MLB precursor – and proved to be an object lesson in being born too early. The Louisville Courier-Journal reported “players objected to Walker on account of his color”, and so his side pulled him from the lineup. As coincidence would have it, his replacement broke his hand in the first inning and refused to come out for the second, forcing Walker’s return. As the newspapers tell it, Walker retook the diamond with the crowd behind him and dazzled them with his warm-up throws and catches while the decision was made to play on. When two Eclipse players still objected to Walker’s participation and repaired to the clubhouse in protest, he was forced to retire. And without him the Clevelanders booked a 6-3 loss.

Related: Steve Dalkowski: the life and mystery of baseball's flame-throwing what-if

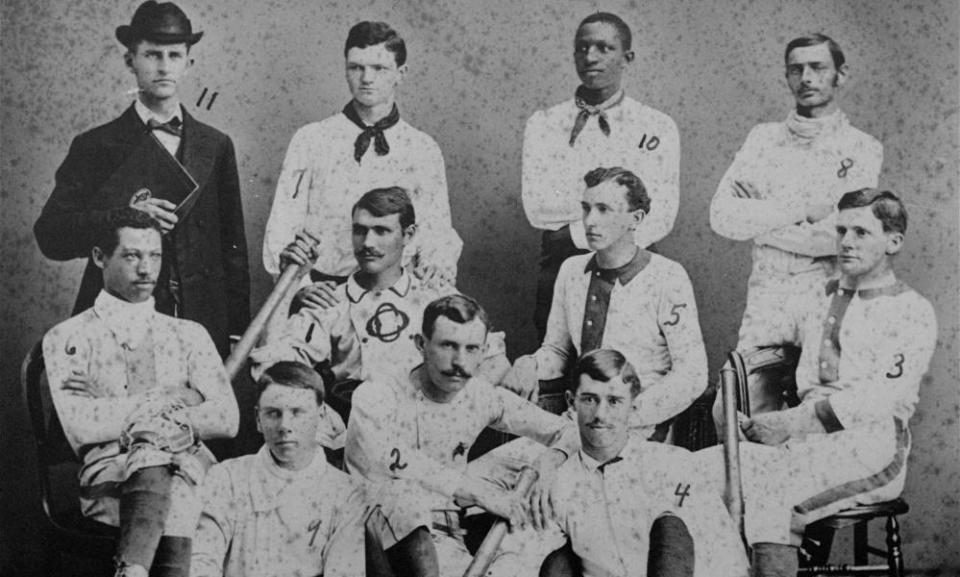

After a momentous year at Michigan that saw him become a father and husband and take an interest in law courses, Walker ditched school for a pro baseball career that had already become a fixation for the sporting press. Not only did newspaper articles swiftly crown him the best at his position, but also “a gentleman in every sense of the word”, according to biographer David W Zang – and all while never referring to Walker’s skin color, stunningly. It was not until his minor-league signing with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League in 1883 that his race became a sticking point. That same year a representative from the rival Peoria Reds introduced a motion in the league’s executive committee banning “colored” players. After the motion was defeated in a bitter fight, Walker went on to lead Toledo to a pennant with his defense – notably donning little more than a helmet and, on occasion, a lambskin glove or two for protection.

When Toledo were promoted to the American Association for the 1884 season Walker became a problem for Cap Anson, the Rush Limbaugh-like figure in charge of Chicago’s White Stockings who would use the catcher to publicly grandstand for segregating baseball. And not surprisingly this would create a fraught environment for Walker’s major league debut on 1 May in Louisville. Whereas three years earlier he had at least won over some fans, this time Walker would be subjected to unrelenting abuse from fans, newspapermen and players on both sides – including two of his teammates who were proud segregationists. “We’ll play this game here,” Anson said per the Toledo Blade, “but won’t play never no more with the nigger in.”

Ahead of a game in Richmond, Virginia, Toledo manager Charlie Morton received a letter threatening to sic a 75-man mob on Walker if he showed up to the park in uniform. “We only write this to prevent much blood shed, as you alone can prevent,” ended the letter, which was published in the 18 September edition of the Toledo Evening Bee. Four days later the Blue Stockings, citing injury, released the 27-year-old Walker after 42 games – a too-small but important baseball number, ultimately – even though he was the third-best hitter on the team and arguably the best defensive catcher in the majors. He never returned, but did play five more seasons with high-ranked but poorly run minor league teams in Newark, Cleveland, Toronto and Syracuse where he remained the “colored catcher”. Alas, Negro Leagues were not yet a viable alternative.

Walker was no less singular a figure after his career in the majors ended. In a testament to his staggering box office power – Walker earned $2,000 for a summer’s work at a time when your average roustabout pocketed maybe $10 a week – he assumed control of a famed hotel-theatre-opera house called the LeGrande and a handful of other grand Ohio theaters when he wasn’t still dabbling in the minors. His stint as editor of The Equator, a Black newspaper exploring the issue of African repatriation, would inspire his 1908 book Our Country Home, which Zang heralded as “the most learned book a professional athlete ever wrote.” He patented three inventions for improving the changing of movie reels, and another for an artillery shell. He was a postman who would serve a year in prison for mail robbery. And then of course in the spring of 1891 he killed a man.

As it turned out, the prosecution’s case against him was a house of cards. Patrick Murray had no pull with his cousin, and his mugshot was prominent in the local police’s rogues’ gallery. The star witness, also named Patrick Murray but better known as “Boodle”, never showed up to testify. Walker’s self-defense argument, which led with Curly striking him in the head with that rock for the crime of being nattily dressed, carried the day. The jury came back with a not-guilty verdict; there was so much celebrating in the gallery that judge George N Kennedy splintered his gavel trying to restore order.

Thirty-three years later, in 1924, Walker died of pneumonia at age 67 after two marriages, three children and a younger brother, Weldy, who followed him into the majors and served as his right-hand man afterward. As much as Jackie Robinson deserves credit for his progressive play, be clear: it was Moses Fleetwood Walker who got the ball rolling. Zang, his biographer, rightly pronounced him “no ordinary man.” The next time you find yourself talking about athletes who changed the game, just remember to say Walker’s name, too.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance