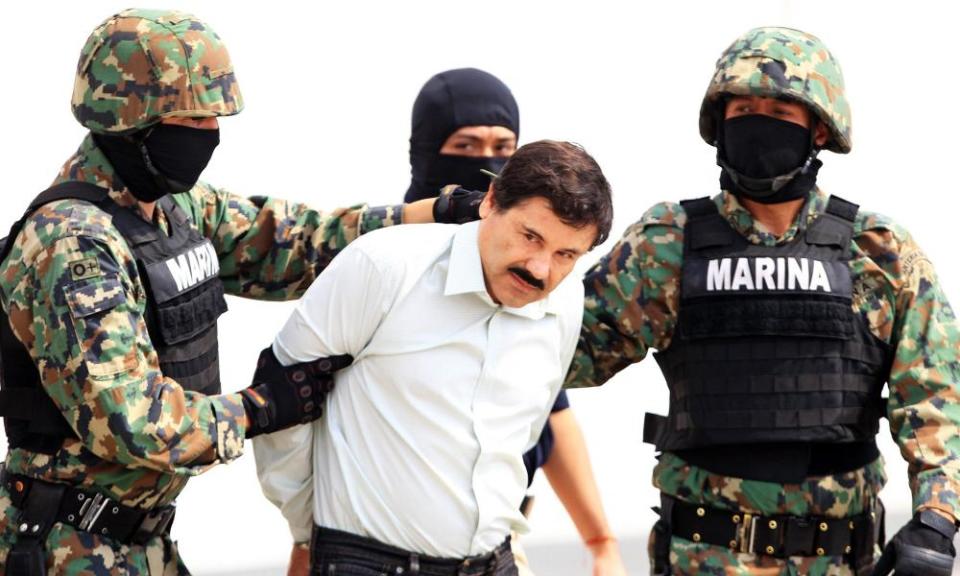

Movie star Sean Penn, drug lord El Chapo and a failed marine raid

He is one of Hollywood’s most acclaimed actors, at one time known as much for his hellraising, turbulent marriage and interest in humanitarian causes as for his films. Now it has emerged that Sean Penn’s taste for adventure – and a potential movie part – almost led him into a trap that had been set for the notorious Mexican drug smuggler and fugitive Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

The tale, recounted in a new book, El Jefe: The Stalking of Chapo Guzmán, sheds new light on an international spying operation set up to apprehend the drug lord who was responsible for ordering as many as 200 murders, according to prosecutors.

Penn and the Mexican-American actress Kate del Castillo travelled to meet El Chapo at his mountain hideout in Sinaloa, Mexico, in 2015. Their purposes were apparently varied – among them the actress allegedly had hopes El Chapo might consider joining her tequila business (which she denies). Guzmán’s was clear: he had dreams of being the subject of a Hollywood movie, and of starting an affair with the soap opera star.

Penn had become involved in a movie project about Guzmán set up by Del Castillo and two accompanying Argentinian producers, and which the FBI hoped would help lure Guzmán out of hiding. The actor would later publish a lengthy article about the trip in Rolling Stone along with a 17-minute video interview with the drug lord filmed in what appeared to be a farmyard. In it, Guzmán was careful to state that it was “for the exclusive use of Miss Kate del Castillo”.

But neither knew that the trip was being monitored by the National Security Agency, the US intelligence agency, which had broken into Guzmán’s encrypted communications. Penn and Del Castillo’s private plane was tracked from Los Angeles to Mexico, and the pair were followed as they travelled into the mountains.

Their interjection in the long chase to capture Guzmán carried its own risk, with US agents scrambled to talk Mexican soldiers out of launching a long-planned raid. The episode left Mexican authorities fuming at Penn and US diplomats concerned that one of their own citizens – and a movie star – might be caught in a gunfight between the smuggler’s bodyguards and an elite force of Mexican marines. The cartel boss was caught four months later but Penn’s unwitting involvement didn’t make it into the trial in New York, though Guzmán’s defence raised the possibility of calling the actor as a witness.

However, the video interview with Guzmán, in which he admitted to working in the drugs trade since the age of 15, made it into evidence. It did little to quell speculation about a more complicated involvement between the Mystic River actor and the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

“There’s a persistent narrative that Penn was working with the US government as a secret agent to lure Chapo out of hiding,” the new book’s author, Alan Feuer, told the Observer. “But if so, I didn’t find evidence of it.

Ultimately, narcissism and jealous paranoia led to Guzmán's downfall – he was unable to live below the radar and constantly tried to get this movie made

Alan Feuer, journalist

Law enforcement saw his involvement as a ludicrous distraction, almost clownish, that nearly derailed a raid on Guzmán by the marines.” According to Feuer, a reporter at the New York Times, even before Penn, Del Castillo and two Argentinian film producers travelled to Mexico, US and Mexican authorities had a lead on Guzmán. “American law enforcement was concerned that Penn’s visit was going to make it more difficult for the Mexican marines to execute a raid. They were also concerned that Guzmán would leave his hideout to meet Penn elsewhere,” he said. But the Mexicans, who had been surveilling them on the ground, were less concerned. “A heated disagreement erupted. The Mexicans seemed not to care at all and wanted to push forward with the raid.”

Ultimately, a storm blew in and the Mexican helicopters could not take off. When the raid was launched six days later, Penn and Del Castillo had left and the marines failed in their attempt to capture their target. Still, the episode weaves into the mythology of El Chapo, who had long nurtured a fantasy of a movie being made about his life. He commissioned a biographer, Javier Rey, but the two fell out over Guzmán giving up 35% of the project’s profits. Guzmán began to suspect that Rey was an informant and hatched a plot to kill him.

The smuggler had already become obsessed with Del Castillo ever since she had appeared in La Reina del Sur (The Queen of the South), a telenovela from 2011 based on the real-life drug queen Sandra Ávila Beltran.

During Guzmán’s incarceration in Mexico’s maximum-security Altiplano prison in 2014-15, Del Castillo, with the two Argentinians, Fernando Sulichin and José Ibáñez, agreed to buy the film rights. After Guzmán escaped via a tunnel dug into the shower of his prison cell, Penn joined the project.

“Ultimately, it was a combination of narcissism and jealous paranoia that led to his downfall – not only because he was unable to live below the radar, but because he was constantly putting himself in the spotlight by trying to get this movie made,” said Feuer.

“In a remarkable twist, he made himself vulnerable to surveillance by surveilling his wives, ex-wives, mistresses and top lieutenants. He thought he was doing the spying but he enabled the FBI to spy on him.”

On Saturday, Guzmán’s new team of lawyers filed an appeal against the conviction on the grounds that a judge had made rulings allowing a jury to hear faulty evidence. They also cited reports that, before reaching a verdict, some jurors sought out news accounts about sex abuse allegations that were barred from the trial.

“This was all about getting Chapo Guzmán,” said lawyer Jeff Lichtman. “There are a variety of appellate issues due to what we think was pretty obviously an unfair trial.”

Meanwhile, Lichtman said, the conditions his client is being held under are “possibly worse” than they were at New York’s Metropolitan Correctional Center. “He has no visitors, he gets a half-an-hour phone call with his lawyers once a week, he can’t speak to his wife. He has no contact with other inmates. It’s exactly what the government was hoping – he’s slowly losing his mind. He’s still the same guy, but the stress is extraordinary and it’s having its effect on him.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance