The nature of the sphinx moth: 'it uses its big-ass tongue to get this guy pollinated'

In The Writing Life, Annie Dillard is watching a sphinx moth preparing to take off. She is on a ship. On its railing there is “a heavy-bodied moth panting”. Dillard is summoning the strength to continue writing her book. The moth is raising its temperature so that it can fly.

Sphinx moths have small wings in proportion to their bodies. Some species are so big, and move their small wings so fast, and hover so effortlessly, that they are sometimes mistaken for hummingbirds.

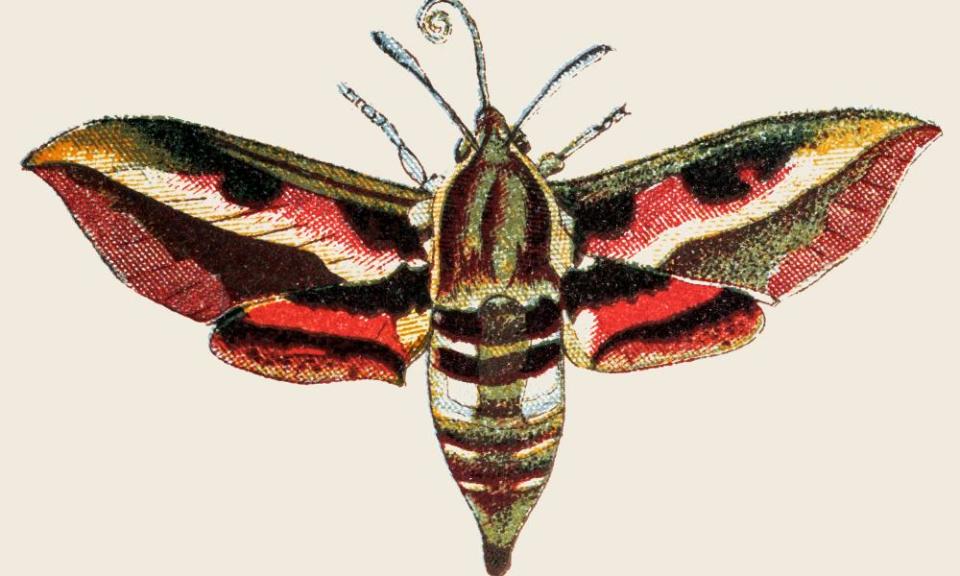

“Beside me on the rail, the sphinx moth raced its engines for takeoff like a jet on a runway,” writes Dillard. “I could see its brown body vibrate and its red-and-black wings tremble.”

Dillard has a thing about moths: she once watched one walking down a driveway after emerging from its chrysalis. Its wings hadn’t had the space to expand and dry out – it had been in a glass jar in her classroom – and it could not yet fly. (Virginia Woolf, in The Waves, writes of days that were “like moths with shrivelled wings unable to fly” and of eyes “like moths’ wings moving so quickly that they do not seem to move at all.”).

I used to have a thing about them too. When I was young I fell prey to a crazed sleep murderer. The moment I switched off my bedroom light, the moth would have a fit, flinging itself along the ceiling. Tap. Tap tap. Tap tap tap. Nothing. TAP. I could not catch it, I could not keep it still. In its relentless, futile pursuit of my lightbulb, it showed no mercy.

Years later, I had a boyfriend who, before we could sleep, would leap about the bed killing mosquitoes. I thought of the moth.

Moths, forever casting themselves into flame and on to lightbulbs, want to die. They are like the ferns in Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief. “I collected ferns for a while,” the Orchid Thief tells Orlean. “They like to die. That’s what they like to do the most. ‘What should we do today? Hey, let’s die!’”

The sphinx moth flaps its way on to the scene in that book, too. It is one of the only species of moth with a proboscis long enough to pollinate the ghost orchid. Or, as the Thief tells Orlean, “A moth uses its big-ass tongue to get this guy pollinated”.

Like most insects, sphinx moths are beautiful and revolting. Some species feed on nectar or honey. Others drink the tears of horses and people.

The moth’s caterpillar, when frightened, lifts its head and tucks its face into its neck, so that its profile looks like that of the sphinx. It may regurgitate food on to its enemies. Some sphinx moth caterpillars resemble pit vipers.

The writer Don Marquis had a newspaper column in the 1920s: poems written by a cockroach named Archy, usually about a cat named Mehitabel. The cockroach, so the story went, wrote the poems by jumping on the keys of a typewriter, which meant there could be no capital letters or punctuation (Archy couldn’t hit two keys at once).

In “the lesson of the moth”, in which Archy recounts his conversation with a moth, he jump-types: “why do you fellows / pull this stunt i asked him”

“we get bored with the routine / and crave beauty / and excitement,” the moth replies. And “fire is beautiful”, he says.

Moths believe, the moth continues, that it is “better to be a part of beauty / for one instant and then cease to / exist than to exist forever”. Archy decides he’d rather have a moderately enjoyable but long life.

Dillard’s moth died, too. It took off, but “it gained height and lost, gained and lost, and always lost more than it gained”. The moth drowned. Dillard realises she is the moth. The one-room cabin where she is writing is the ship’s rail.

“The task was to change intellectual passion to physical energy and some sort of narrative mastery, from a standing start,” she writes.

Inertia and action. Stillness, momentum. Stopping. Starting. Charging ourselves up for the year ahead knowing we will inevitably, after a short flight or a long haul, come to a complete standstill. We will stare at the sea. Then we will begin to charge our blood again.

As Elizabeth Bishop wrote, “what the Man-Moth fears most he must do, although / he fails, of course, and falls back scared but quite unhurt.”

“The Nature of …” is a column by Helen Sullivan dedicated to interesting animals, insects, plants and natural phenomena. Is there an intriguing creature or particularly lively plant you think would delight our readers? Let us know on Twitter @helenrsullivan or via email: helen.sullivan@theguardian.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance