NHS Covid app developers 'tried to block rival symptom trackers'

NHSX, the health service technology unit responsible for the government’s failed contact-tracing app, attempted to block rival apps to protect its own, hampering efforts to track the early spread of the coronavirus.

Developers were urged to stop work by NHSX and the Ministry of Defence, who told them their apps might distract attention from NHSX’s app when it was launched. Last week the app was abandoned after three months, with work beginning on an alternative design without any deadline.

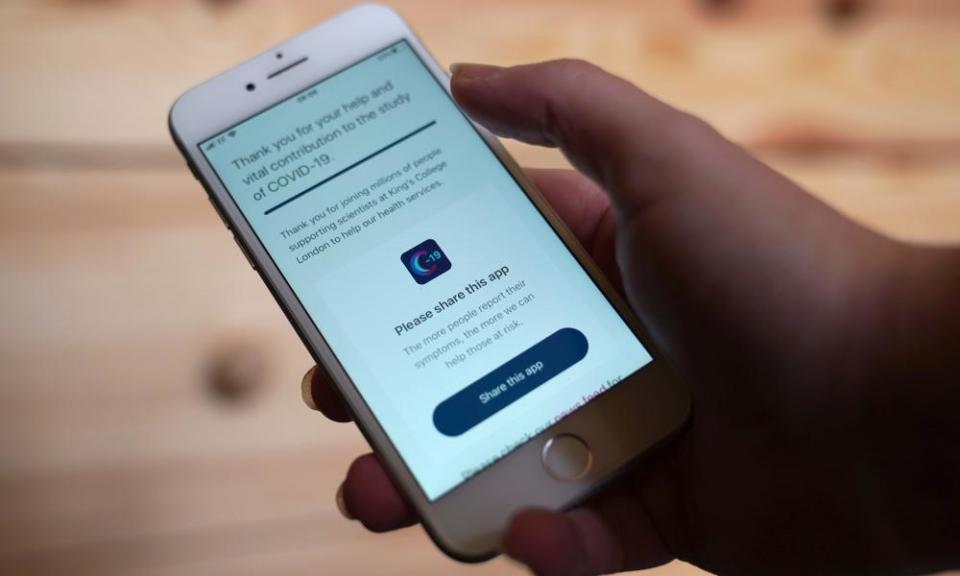

Prof Tim Spector, of King’s College London, said that NHSX had treated his Covid symptom tracker research team as “the enemy”. “We were hampered from the beginning, in March when we first contacted NHSX,” he told the Observer. “They were very worried about our app taking attention away from theirs and confusing the public.

“Lots of signals went to places like the universities, my university, the medical charities and the royal colleges not to back our app because that would interfere with their one.”

When the pandemic hit the UK, tech workers, academics and health professionals responded to Boris Johnson’s call for a national effort by creating smartphone apps to help track the spread of the virus.

The Covid Sympton Study app has 3.5 million users and has helped chart the emergence of symptoms such as the loss of taste and smell. Evergreen Life, with 800,000 users, has been working with the universities of Liverpool and Manchester and spotted signs of the outbreak in Middlesbrough before tests had been carried out. The government’s app, meanwhile, was downloaded by tens of thousands of people on the Isle of Wight and never formally launched.

The rival apps could still form a vital part of the early warning system if, as some scientists fear, a second wave of Covid-19 hits the UK. The Covid Symptom Study app indicates that while the number of people reporting symptoms across the UK has been decreasing, numbers in London have remained static for the past three weeks.

Spector said that although people in the NHS had wanted to work with his team, they told him privately that everything needed to go through NHSX, which was set up by Matt Hancock after he became health secretary, and previously operated outside the main structure of the health service. “We naively thought they would sort of take our app over or incorporate them into one,” he said. “The whole point was to help the NHS, to find the hotspots so they could get the resources to the right hospitals.”

Instead, he said he was told the app was a problem. “The idea was that this NHSX app was going to be the saviour, another world-beating thing,” Spector said. “It was going to be an all-singing, all-dancing app that does everything: diagnoses you, it tells you about tests for you and who you’ve come into contact with.

“They were saying: ‘This will make your app redundant’. Their app would come out, there’d be a huge blaze of publicity and everyone would drop our app. We said: ‘Well, if that does happen, we’ll hand over and work with you, it’s in the interests of the country.’ Theirs just got more and more delayed – nothing ever happened. Ours got more and more successful,” Spector said.

Had ministers backed the app in England, more people would have signed up more quickly, Spector said. “We would have got more fine-grained data earlier. Their attitude prevented other branches of government working with us.” Users of the Covid Symptom Study who report symptoms can now order a test directly through the app. “That would have started earlier,” he said.

Spector said he was working with the joint biosecurity centre, which has been set up to create an early warning system for Covid-19 and other diseases. “Plenty of people within the NHS have been very helpful,” he said, naming Sir Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief scientific adviser. King’s will be launching a campaign on Monday to persuade the government to support the app.

The devolved administrations in Wales and Scotland also adopted the app early on. “We have proportionally many more users there,” he said. “I know, from speaking to other people from the Ministry of Defence who were helping out, they put even more pressure on some of the other apps to close them down early.”

NHSX has set up “Project Oasis” to gather data from eight tracking apps. One technology firm characterised the relationship between them as “keep your friends close and your enemies closer”.

Ian Gass of Agitate, which set up Ink C-19, an app designed to make reporting symptoms as simple as possible, said he was approached by the government in March and described the interaction as “not friendly”: “Not that it was aggressive, but I got the impression that there was just a lot of panic going on in governmental circles, and they didn’t know what to do or how to do it. They intimated that they’re doing stuff, and we don’t want others doing it.”

Agitate is a leading expert in tech security and Gass tried to advise NHSX in March that its app design, which attempted to use Bluetooth signals to sense when a phone came close to another, was flawed. In theory, the app was supposed to keep a record of other phones, and if a person developed symptoms, the app could send an alert to those phones. Yet the app only recognised 4% of Apple phones using Bluetooth.

“The whole overall approach at the moment is this weird, almost paranoid state where the government says publicly that they’re asking for help, but then they don’t want it,” Gass said.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance