The NHS surgeon challenging Musk’s technology to connect your brain to the internet

Sake the monkey is tapping away on a virtual keyboard. The macaque, encouraged with plentiful bribes in the form of a sweet treat, types out the message “welcome to show and tell”.

Except Sake is not using his fingers. The virtual keyboard is being controlled with his mind, via a chip implant from Neuralink, a technology company founded by Elon Musk.

“To be clear, he’s not actually using a keyboard,” Mr Musk admitted. “He’s moving a cursor with his mind to the highlighted key. Now technically, he can’t actually spell, I don’t want to oversell this thing, because that’s the next version.”

At Neuralink’s “show and tell” event in November, the company showed off a range of technical innovations in developing a “brain-computer interface”.

The idea behind this technology is that one day, humans will be able to control computers with just their thoughts. They could connect to the virtual web and access a plethora of digital information using only their minds, turning people into true cyborgs.

In the more immediate future, the benefits could include linking up people who are paraplegic or “locked in” from illness or injury to computers, giving them a much faster means of communicating via a keyboard or computer screen.

Musk has claimed the company is a mere six months away from testing its technology in human brains. Its Neuralink chips have around 16,000 tiny electrodes and will, ultimately, be implanted using the company’s R1 robot into a gap in the skull, threading 64 threads into the brain.

The world’s second richest man said in November: “We’ve submitted, I think, most of our paperwork to the Federal Drug Administration and we think probably in about six months we should be able to have our first Neuralink in a human.”

Musk has promised his technology could one day be used to enable advanced prosthetics, such as by wiring a chip into the brain that connects to a camera to help the blind “see”.

But his claims have prompted plenty of scepticism, not least, just how many people, even those with life changing injuries or long-term disabilities, are willing to risk inserting a chip made by the owner of Tesla and Twitter into their brains.

Some start-ups think there are better alternatives. In the UK, Imperial College spin-out Cogitat has been developing software that can more accurately read brainwaves using existing electroencephalogram (EEG) scanning machines.

The company’s co-founder and chief executive, NHS surgeon Dr Allan Ponniah, believes it has effectively trained its algorithms to pick up brain signals that can check if a person is trying to use their hands or feet, and believe one day they will have enough data to allow more granular movements using mind control.

Dr Ponniah says: “Other people in this field are using invasive technologies, they require some kind of operation.”

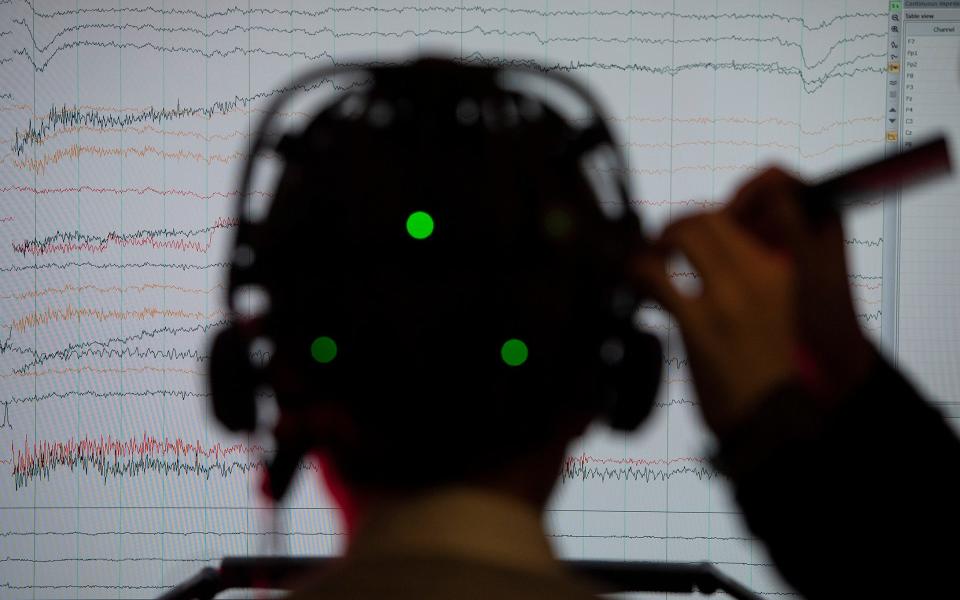

In a demonstration with The Telegraph, Cogitat strapped a non-invasive EEG machine, which features a dozen electrodes that maintain contact with the scalp, rather than the skull.

Dr Ponniah says: “We put the electrodes on the surface of the scalp, rather than inside the skull. People did not believe it would be possible to get an accurate motor signal from the outside of the scalp, because there is a lot of noise. What we have done is used artificial intelligence to find that signal amongst the noise.”

Once strapped in, Cogitat users are able to play simple games using mind waves. In one video game, users clench and unclench their fists to accelerate a jet ski. Data is gathered from touchpads, which is then matched to a users’ brainwaves.

When the touchpads are turned off, brain signals that transmit through the EEG headset alone are used to play the game. Cogitat collects data from the motor cortex, which controls movement functions in the brain, that are then translated into virtual movements.

In 2021, the team beat the US army in a competition to demonstrate EEG and brain technology in a competition sponsored by Facebook’s Reality Labs, its metaverse division.

The technology is also ready to use now. Cogitat is working on a trial at the National Hospital for Neurology to use its technology for stroke rehabilitation. Neurologist Dr Robert Simister says the trial combines Cogitat’s games with therapy, which he believes will lead to better recovery.

Ultimately, Cogitat believes its technology could be used for controlling prosthetics or interacting with a virtual world or games using only thoughts.

There are potential challenges to this approach. The signal from the brain is not quite as accurate as a direct connection that Neuralink is using. Cogitat’s brain games remain relatively rudimentary, compared to Musk’s efforts. It is also tiny, with a small amount of funding through the Creator Fund and angel investors including William Tunstall-Pedoe, who helped invent Amazon’s Alexa.

However, Neuralink has its own difficulties. Gathering the data required for its algorithms is problematic. Very few people are likely to be willing to allow Musk to drill a hole in their head.

“In order to collect data, you would need to drill into somebody’s skull. For us, we just put a device on somebody’s head,” Dr Ponniah says.

Regulators have also raised concerns about Neuralink’s research and its ethical approach. Reuters reported that US animal welfare authorities are investigating the company over the deaths of multiple test subjects.

Reuters reported that 1,500 animals have died during four years of testing at the company, including monkeys, pigs, sheep and mice. Neuralink has not responded to the allegations. Musk has previously insisted the company is not cavalier" with its experiments.

In February last year, it admitted to euthanising several animals as part of its research. “Two animals were euthanised at planned end dates,” the company said, while “six animals were euthanised at the medical advice of veterinary staff”. The animals were killed due to device failure, infections and “surgical complication”.

Katja Kornysheva, an assistant professor in human neuroscience at the University of Birmingham, is sceptical that invasive surgery is the way forward. “The risk profile and costs of invasive methods are substantial. Clinical risks can include infection, haemorrhage and mechanical brain tissue damage.”

The innovation, she says, is best used by “a very small pool of patients with severe disability”.

Neuralink is facing plenty of other, well-funded, competition. One start-up, Synchron, has raised more than $200m from investors including Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. Its technology is already being used in human trials.

It uses a device similar to a stent, a tiny set of wires which is placed in blood vessels near the brain. This can then be used to translate brain signals into simple commands, such as typing on a virtual keyboard. The company describes it as “bluetooth out of your brain”. Trial patients are already using the tiny machine to control computer screens.

Elsewhere Meta, the owner of Facebook, is developing a non-invasive EEG scanner that is using artificial intelligence to try and translate brainwaves into words.

Right now, it is these invasion can theoretically translate signals with more detail than Cogitat’s non-invasion method. But that could change. Kornysheva says: “Offline machine learning technologies have shown that these non-invasive signals carry a much richer information about movements than previously thought.”

Musk’s brain-machine chips might seem like science fiction. But mind reading technology, in one form or another, is closer than you think.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance