Old v new, strata fees, cladding and more: all you need to know about buying a unit

Ask most prospective homeowners and they’ll probably tell you they’d rather buy a house than a unit.

But the financial reality is that apartments are not as expensive so they might be a better bet for people who want to get on to the property ladder. House prices have jumped sharply in Sydney’s inner west, north-west and southern suburbs during the recent market rebound, according to recent figures from Domain, far outstripping units. Median house prices rose 4.8% in the September quarter; units 2.6%.

Units are also more plentiful. On Thursday the research company CoreLogic confirmed there aren’t many houses on the market. Things are better than they were in winter, but in Sydney total listings were still down 23% in November compared with a year ago. In Melbourne they are down 15.7% and in Perth 16.6%. Of the properties available in Sydney and Melbourne, almost half are units: 48.2% and 47.2% respectively.

Related: From freefall to boom: what the hell is happening to Australia's housing market?

Not surprisingly more people live in apartments than ever before. The 2016 census found about 10% of the population live in a unit. There is one occupied flat for every five houses, compared with seven back in 1991.

So if you’re thinking about taking the plunge in the apartment market but are worried about whether to buy old or new, building quality, cladding, strata or owner corporation fees and even ending up in a block full of Airbnb rentals, what should you look for?

If I buy a unit, how do I check it’s not dodgy?

The structural problems with the Opal and Mascot Towers in Sydney have been well publicised and have raised a lot of questions for people interested in buying new or recently built units.

Owners of apartments in the Mascot Towers block, which was evacuated in June when cracks appeared, faced the prospect of taking out huge loans to fix the problem as the New South Wales government considers recommendations to protect owners more effectively from substandard building practices.

In the meantime, there are two ways to check for basic information. One is through a seller’s certificate which in New South Wales will give some details of strata accounts, but it’s typically available only for people who have committed to buy.

It’s far better to order a proper strata or body corporate inspection from professionals to find problems such as building defects, litigation issues, special levies that unit owners might be liable for over and above strata fees, and whether there’s enough money in the sink fund to pay for future repairs. These inspections will cost about $250 to $400.

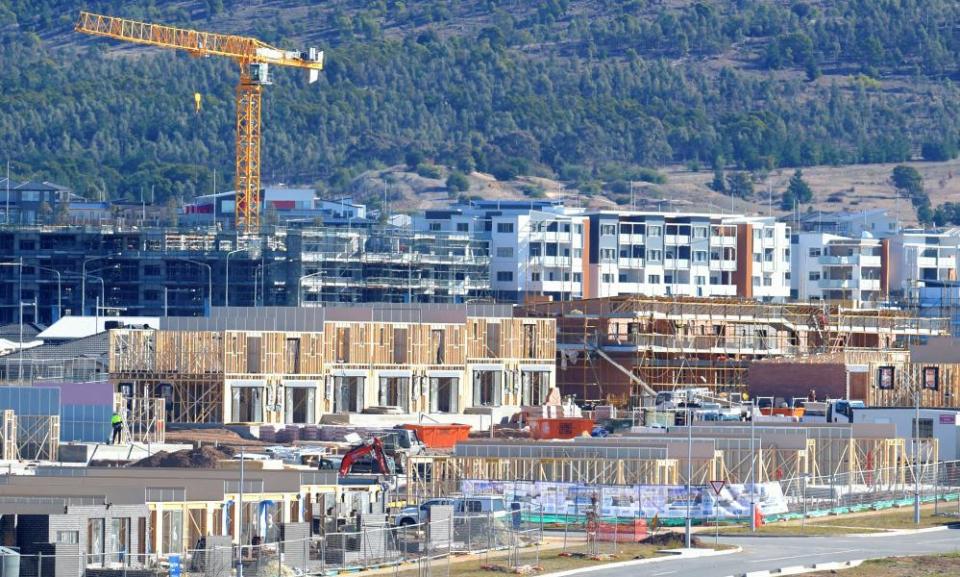

In Victoria it’s known as an owner’s corporation certificate and can be obtained on request. The cost depends on how quickly it is needed but starts at around $140 for delivery in 6-10 days. Tony Gerace, of real estate agent Burnhams in Footscray, Melbourne, where up to 4,000 new apartments are being built, said it was an essential step for buyers in Victoria. “Not everyone knows about this. But if it was me buying a unit, it would be the first thing I would do.”

What about fees?

This is important and should be flagged up by a strata or body corporate report. Strata fees are generally between about 0.3% and 0.7% of the property’s value, but can be up to 1.2% if it has facilities such as a gym, swimming pool or concierge. So while those add-ons may make the unit more attractive, they come with a price. “High fees can obviously be a drain on your cashflow, but can also be off-putting to future buyers so can stymie capital growth in your unit,” says Pete Wargent, a buyer’s agent in Sydney.

What about cladding?

This remains a very serious issue in Australia and around the world after the Grenfell Tower disaster in London. Many high-rise developments in Australia have been built with flammable cladding. In Victoria the government is spending $600m to identify and fix the buildings. But in NSW the extent of the problem has been concealed from the public, so buyers have to find out for themselves if their building has the potentially lethal material. Adding to the sense of crisis, the Australian Institute of Building Surveyors said this week that the professional indemnity insurance market would collapse within 12 months because insurers will not cover builders and developers for cladding problems. It says the federal government has to step in and underwrite the industry.

Why is the whole process not more transparent?

Deregulation of the industry at state level has prevented a clearer system from developing, leaving people “buying blind”. Michael Teys, a strata law expert and academic at Deakin University who is researching due diligence issues, says he recently visited New Zealand to see how its system worked and was impressed.

“I was amazed by the transparency,” he says. “You get a complete record of the building, and it’s a really good system.

“But we don’t have that here in Australia and the information can be quite difficult to get. A lay person would struggle to get what they need so it’s madness to be buying and not have that check done by a professional.”

A study this year by Deakin showed that the number of building defects was growing, with water damage from leaking roofs and walls the most common. “Defects are endemic and are now the rule rather than the exception,” says Teys.

Can I check out the developer or builder?

Yes. Start by checking if they’re still in business. There are many cases where a company might work on a building but fold when it’s completed, leaving no avenue for restitution if there are problems down the track. Steve Jovcevski, a property analyst at the consumer website Mozo, says it’s crucial to do due diligence in this area. “You’ve got to make sure who the builder is, who the developer is. Is the builder a tier one builder?” he says, meaning the biggest companies. “The bigger the builder, the less likely they are to go bust. If there are defects, they are more likely to be around to fix it.”

What about buying off the plan?

The same rules apply. Check out the developer and the builder. Since the building is still being built, this might be easier. You can go and see them at work. Off-the-plan deals also have the big advantage of saving a significant amount on stamp duty. The tax is payable only on the land value, rather than the home value, so it’s noticeably less. And in a rising market it can make sense because the unit might be worth more than you paid for it by the time you complete, typically two years after putting down a 10% deposit. However, prices can also come down and flats can be worth less than you paid.

Is it better to buy an older place?

Going for vintage will probably ensure that you don’t encounter too many serious structural problems, because enought time will have elapsed for any issues to come to light. Also older places tend to be low-level blocks built before the craze for high-rise living kicked in this century. Wargent also says that older places “tend to have a higher land value content per unit and more scarcity value than larger developments”. Older buildings are less likely to have underground parking and storage, although they may have attractive period features. They may also lack the large balconies of many new developments.

How do I know if it has noisy residents or is full of Airbnb rentals?

Ask around. These issues may have been raised at strata meetings. Otherwise try asking the agent or residents. Jovcevski says it’s important for the feel of the building to check the ratio of investors to owners: “You don’t want a place with a lot of Airbnb rentals. Some new developments around Central station in Sydney, for example, and Waterloo are well known for it and have a lot of student accommodation, so that might create a problem.” Conversely, if you want to rent your place out on Airbnb when you’re not at home, check with strata whether it’s allowed.

Anything else?

Just the obvious stuff. Get the contract checked by a solicitor or conveyancer, and check whether there are any developments planned that might change the ambience of the neighbourhood.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance