Drug companies that benefit from the war on opioid addiction

The opioid crisis in the United States is a medical and societal tragedy so jarring that it has even united Republicans and Democrats in unanimous condemnation. Between 1999 and 2017, nearly 400,000 people in the U.S. died from an opioid overdose, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That includes nearly 48,000 deaths alone in 2017.

Currently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 130 people in the U.S. die every day from opioids. Americans are now more likely to be killed by opioids than in a car accident.

This epidemic is a symptom of deep issues in our country—including stress, income inequality and social mobility—which I recently delved into a bit. Addressing those problems will take a great deal of work and time. But the opioid crisis needs to be tackled on a more micro and immediate level, as well.

And the later point directs us to the pharma industry because, of course, the opioid crisis is a shocking disgrace for a group of drug makers and drug distribution companies that have foisted addictive narcotics on our society at levels far beyond any plausible medical need.

There are any number of ways of showing this. But here’s one factoid that sums things up nicely: The U.S. has about 4.5% of the world population. But according to data from the International Narcotics Control Board, which keeps track of global opioid use, the U.S. consumed 72.9% of the world’s oxycodone (aka, Oxycontin) in 2016. Explain that Mr. Pharma executive.

Investing in companies that are part of the solution

How culpable these companies are is now being adjudicated in a wave of litigation but already some degree of responsibility has been established. These companies helped cause this scourge.

I’m sure you’re shaking your head at how terrible this is, but let me ask you a question: Do you own any of the stocks of the companies that are part of the opioid ecosystem?

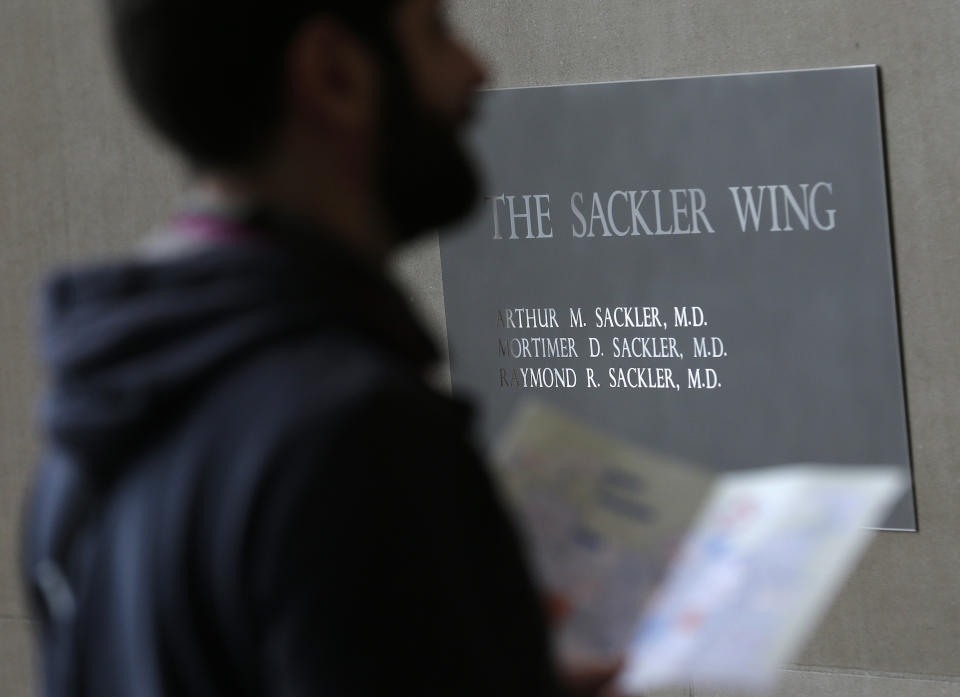

In terms of the company at the center of this storm, the answer is almost certainly no, as Purdue Pharma, make of Oxycontin, is a privately owned by the Sackler family. That company now faces all kinds of litigation, including a lawsuit filed last week by New York’s attorney general accusing it of creating an opioid epidemic that has ravaged the state and caused “widespread addiction, overdose deaths, and suffering.” The Sacklers have faced other blowback, including high-profile museums where the family gave major donations terminating those relationships.

But what about other companies that manufacture opioids? There’s Endo Health Solutions; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries subsidiary Cephalon; Johnson & Johnson’s subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals; and Allergan, formerly known as Actavis. And there’s another group of complicit companies, the distributors, chiefly, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson, which have allegedly profited from selling ridiculous amounts of opioids to pill mills around the U.S.

It’s not unlikely that you own one or more of these stocks in your portfolio or in a mutual fund or ETF. If you’ve invested in companies that are part of the problem—or even if you haven’t—have you considered investing in companies that may be part of the solution?

There are a number of drugs being produced to treat opioid addiction, but distribution in the U.S. has so far been slow. That could be an opportunity for Alkermes, which makes a drug called Vivitrol and Indivior, producer of drug that combines buprenorphine and naloxone called Suboxone, as well as a number of companies including Hikma and Mallinckrodt that make methadone. Just be aware that all these companies are trying to address a complex problem fraught with legal and policy nuances, (more on some of these companies in a second).

First know that more opportunities for these companies appear to be coming. The FDA has called for greater access to opioid addiction treatment drugs. And last October, President Donald Trump signed an opioid bill into law that “lifts restrictions on medications for opioid addiction, allowing more types of health care practitioners to prescribe the drugs,” according to Vox. Also, Sen. Elizbeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts and 2020 presidential candidate, introduced the CARE Act last year to address opioid epidemic.

So why has there been so much resistance to what is called MAT (medication-assisted treatment) for opioid addiction?

‘We need dramatic action’

Keith Humphreys, PhD, a researcher at Stanford University and author of a study that found a mix of treatment approaches could save thousands of lives in the next decade, explains that problems go back to methadone, first used to treat opiate addiction back in the 1960s. “It was politicized, there were protests from right and left about methadone,” he says. “Also there are some clinics who do bad things. That are careless in prescribing. All of that together the government responded with a ferocious level of regulation. And it’s just kind of stayed there.”

Consider, though, addiction versus other diseases: “If we had the level of use of effective chemotherapy for cancer that we have for effective addiction medication for addiction, there would be riots in the streets,” Humphreys says. “People would not tolerate so few cancer patients getting effective treatment. Because of negative feelings people have about addicted individuals, the stigma, this appalling situation continues. As a result, people's lives who could be saved instead die needlessly.”

The oversight and regulations for these drugs right now is onerous. “The amount of monitoring is astonishing and it doesn’t need to be that way,” Humphreys says. “We gave out lots of Oxycontin which is more dangerous and with less regulation.”

So getting back to those companies that make drugs which treat addiction. First, biotech company Alkermes is headquartered in Dublin, Ireland. Its stock, now trading for $36, has been all over the place over the past five years. The company, which has a market cap of $5.7 billion, hasn’t turned a profit recently. Last year Vivitrol sales climbed 11% to $83.8 million. This year Alkermes expects Vivitrol sales to be $330 billion-$350 million. (The company did $1 billion in total sales last year.) Vivitrol is expensive and in November, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) opened an investigation into the company’s marketing practices.

Indivior, based in Virginia, is a producer of drug called Suboxone. The company was spun off of British giant Reckitt Benckiser in 2014 and has a market cap $726 million. The stock lost half of its value the day a court ruled in favor of a company seeking to develop a generic version of Suboxone back in November. Indivior relies primarily on revenue from sales of its drug Suboxone in the United States — a country that accounts for 80% of its revenue.

Again, these companies may not be slam dunks, but they are worth exploring. And in case you’re wondering if it’s a bad thing to invest in companies that benefit from drug treatment, one expert says don’t worry. “I certainly don’t mind if people who save lives of addicted people make money, like people who save lives of people with cancer,” says Humphreys. “Methadone is a generic drug, less than a dollar a day.”

Right. And the government needs to move more quickly and give people better access to treatment like these drugs. “[We] need dramatic action,” says Humphreys. “[We] needed dramatic action to turn around AIDS epidemic, [and we] need dramatic action to turn this around.”

Amen to that.

Andy Serwer is editor-in-chief of Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

Why Facebook, Google, and Twitter don’t want to be media companies

A simple but radical solution to solve Facebook’s problems

How Donald Trump strengthened The New York Times and strengthened a billionaire’s fortune

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance