Pax Narco: Life, Death and Drug Money in Culiacán, the City of El Chapo

When the shooting eventually stopped, the rains would turn out to be a blessing. But on the morning of 17 October 2019, as crime reporter Ernesto Martinez drove down into the city of Culiacán, the weather seemed ominous.

It had barely rained in the city for months, but now storm clouds squatted over it. The deluge of the last few days had been so heavy that many schools had suspended classes and sent their students home. Later that morning, when the firefight between government forces and the Sinaloa cartel erupted, some of those empty buildings would be peppered with bullets. Were it not for the weather, "I have no doubt many kids would have died," Martinez tells me.

A local crime journalist, Martinez has been reporting on drug violence in Culiacán for two decades. The city of 800,000 is located in the northwest of Mexico, around 300km from Mexico City, and is the capital of Sinaloa state. It is also the home city of the Sinaloa Cartel, the drug-running syndicate that was founded by Guzman 'El Chapo' Lopez in the late Eighties. Prior to El Chapo's arrest and extradition to the US in 2017, Sinaloa was deemed by US intelligence to be the most powerful drug trafficking organisation on earth.

In a city run by narcos, shootouts are a daily occurrence, so when Martinez got a tip that something was kicking off in the city centre he assumed it was just a skirmish between gang members. But when he arrived on the scene he witnessed a running street battle between heavily armed narcos and government soldiers. The narcos had swarmed the streets in an attempt to free El Chapo’s son, Ovidio Guzman Lopez, who had been arrested in a military operation a few days earlier. Now, they were waging an all-out assault on the city’s official security forces.

Hundreds of narcos armed with high-calibre weapons had stormed the city, setting fire to vehicles and blockading 19 roads and bridges, bringing traffic to a halt and preventing people from fleeing. Martinez, trying to cover one of the battles, was pinned down for two-and-a-half hours, but as he crouched for cover, rounds cracking inches above his head, it felt endless. “I definitely didn’t think I’d survive," he says. "[I was] hunched down, hearing, seeing, feeling the bullets going around me. I couldn’t move. I was certain, if I moved just one inch, I’d be hit. No-one would be that lucky to get out of an event like that unharmed."

Eventually, Guzmán Lopez was released, purportedly to prevent an escalation of the violence that might endanger civilian lives. Locals, however, see it as a naked display of the unofficial authority, and impunity, the cartel enjoys in its Sinaloan stronghold. In June this year, Mexico’s divisive president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely referred to as AMLO) changed the narrative once again, this time saying that he personally ordered the drug lord’s release, “so as not to put the population at risk.” He’d previously insisted that his security cabinet made the call.

As Mexico struggles with overwhelming numbers of Covid-19 cases, the spectre of drug violence continues to loom. Just days after AMLO rehashed the Culiacán story, Mexico City’s chief of police was shot and injured in a dramatic assassination attempt in Lomas, one of the capital’s upscale neighbourhoods. The attempt, which also saw two of his bodyguards killed, was blamed on the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), one of Mexico’s most powerful drug gangs, which had emerged in the late-aughts when groups loyal to the Sinaloa started to splinter.

El Chapo

The Sinaloa Cartel got its start in the Eighties as a marijuana producer, before specialising in transporting cocaine into the US from Central and South America. “In the Nineties they became the bosses,” says Guillermo Ibarra Escobar, an urban economist at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, who also authored a book on Culiacán’s narco culture called Culiacán: City of Fear. “When [former president] Vincente Fox came to the presidency the state governors had a lot of independence and they allowed the cartels to become a kind of narco republic, who shared the power like a shadow government.”

Over the course of his reign, El Chapo, a Sinaloa native, amassed an estimated fortune of $14 billion, according to the US Justice Department. In 2016, however, he was arrested for the third and – so far – final time (both prior incarcerations had ended in cinematic flights from justice: first, in a prison laundry cart; second, through a tunnel dug into his shower block). He was extradited to the US before he could flee again and is now serving a life sentence in near-isolation in the high security “Supermax” Florence prison in Colorado – known as the ‘Alcatraz of the Rockies’. El Chapo may be gone, but the Sinaloa Cartel, which he turned into a genuine force and perhaps the biggest supplier of drugs into the US, continues.

The Sinaloa Cartel, which in 2009 was subjected to sanctions by the Obama Administration under the Kingpin Act, is described by the DEA as a “former hegemon” of the drug trafficking landscape, with that qualifier applied partly due to to El Chapo’s removal. His absence has created a power vacuum of sorts, but the cartel retains much of its influence. Some analysts assert that the Sinaloa, which became somewhat decentralised following the removal of its co-founder, “remains powerful given its dominance internationally and its infiltration of the upper reaches of the Mexican government.”

As the cartel’s hometown, Culiacán has a reputation for bloodshed. Though numbers vary, it floats around the top 20 most deadly cities on earth, with an annual murder rate of between 50 and 70 people per 100,000. However, this figure only includes the documented killings – many more victims are simply disappeared.

According to Renato Ocampo Alcántar, executive secretary for the State Public Security bureau, this number is decreasing – official figures show the annual murder rate decreasing by almost half between 2017 and 2019, from 1,354 to 776. This runs counter to national trends – 2019 was the deadliest year on record and in March 2020, as the country poured resources into fighting Covid-19 rather than the cartels, killings spiked to a record 2,585.

Black Thursday

While Martinez was seeking cover, his daughter-in-law and her three-year-old daughter were forced onto the side of a road by sicarios – narco enforcers – who then set their bus ablaze as a barricade to prevent government reinforcements reaching their position.

Later, he shows me a video of his granddaughter on his phone. She’s leaning against a bed pretending to talk to him on a toy phone, recreating the moment when she and her mother were led off the bus at gunpoint. “Get down!” she says, crossly, imitating the gunmen. “Boom boom boom boom.” She pauses and raises her fist upwards as if carrying a rifle. “Boom!”

His son, a fireman, was also caught up in the attack. As his engine was racing to the scene, it was intercepted by a pickup truck that had an FN Minimi machine gun mounted on the flatbed. The gunman swung it round to point at him. He thought that his time had come, Gonzalez says, but the sicario swivelled back round again, to face forwards and the oncoming firefight.

Others were not so lucky. Thirteen people were killed in the attack, according to the official death toll, including three civilians who were caught in the crossfire. It was a terribly conceived raid which, hours later, saw security forces release Guzmán Lopez in exchange for a cessation in the shooting, before it could engulf the city and cause more civilian deaths.

Ocampo Alcántar, the public security official, says that the attack was a wakeup call to the endemic violence in the city. “In Sinaloa we have gotten to the point that we’ve normalised the crimes, it’s seems to be an everyday thing but it’s not. [Black Thursday] showed violence is not a normal thing.”

He denies, however, that there is anything resembling a truce between the cartels and the security forces. “Not now and not before. We’re still fighting these crimes and the organised crime forces. We cannot convene with these people. Organised crime in Mexico is penalised, we will never combine with them.”

City of Fear

After the attack the city briefly spasmed in fear and grief but by the time Esquire visited three weeks later, shortly after the Mexican festival of Day of the Dead, a status quo of sorts had returned to its streets. Ibarra, the academic, calls this truce “Pax Narca” – the simultaneous existence of the state and the narco state, a tacit understanding that if cartel violence against the populace is suppressed, out-and-out attacks by the security services on the narcos will be as well.

And so Culiacán continues to live under this uneasy truce – calm in the city in exchange for a tacit agreement to cohabit, which comes at the price of any real freedom for its residents. The events of 17 October didn’t change this dynamic; it just highlighted it and emphasised the cartel’s reach, Ibarra says.

This disjunction is made viscerally apparent when, as we drive through Culiacán’s teeming streets, we hear radio ads urging people not to commit murder. Those you kill are someone’s father, son, brother, friend, the voiceover intones.

At the Forum, a plush mall in the centre of town which wouldn’t be out of place in the ritzier parts of LA, Culichis – Culiacán natives – mill around. Nineteen-year-old Oscar Antonio, a nutrition student, sits in the food court, eating spicy chicken wings with two friends. He says he learned about what was happening from home, and that through social media – not official channels – he was advised to stay there. He says some students he knows were in the thick of it, and sent round videos that they were recording live.

“I always knew that in Culiacán these kinds of things could happen [but] when Black Thursday happened, I felt insecure. For the first time I felt that I could be affected by it,” he says.

“It’s very obvious to spot the people who are in cartels, they dress very fancy, they have very nice cars, it’s very obvious that the money was made in a bad way. Personally I haven’t been offered [to work for them] but I have friends who have been offered and joined.”

“The police are only ornaments”

During our visit to Culiacán we’re called to a crime scene in a working-class neighbourhood north of the Culiacán River, which bisects the city, that was created in the Eighties to provide housing for government employees, many of whom are now pensioned. A man in his mid-20s had been shot in the head, the bullet entering his left temple and exiting through the right jaw. As he tried to escape he had smeared blood across the white paintwork of an apartment block’s open staircase, before collapsing. He is taken away in an ambulance, still breathing.

One of the assembled police has a Velcroed patch of the Punisher logo, from the Marvel comic book about a bloodthirsty vigilante, affixed to his flak jacket. Another patch states his nickname – Boss – and blood type – O+. He says he’ll guard the scene for another hour or so.

Carrying a Beretta ARX160 semi-automatic rifle and a .40 calibre pistol in a side holster, he wears a thin police-issue balaclava. Attending murder scenes like this is a daily occurrence for patrolmen like him, and he accepts the risks that come with being a cop in a city where gangs are constantly fighting. “When you leave your house, there’s always a question – will you come back?”

Across the street, Juan, a 55-year-old city metrobus driver, sits with two neighbours in the tiled porch of a two-storey house. These shootings long ceased to surprise them, but this latest attack makes them wary for the neighbourhood’s future. “Things [like this] are happening every week,” he says.

On Black Thursday, a firefight erupted nearby and Juan saw a number of police vehicles on the roads near his house. There were weapons and uniforms in the cars, he says, abandoned by cops who had fled the shooting. Juan had been driving his route around the city’s downtown area when a crying lady boarded the bus and begged to be driven to safety. He didn’t understand what was going on until more people jumped on. Juan's bus got a flat tyre driving them out of the city; when he took it to get repaired, the mechanics showed him six bullet casings embedded in the rubber.

“It’s good that they [halted the attack] to save civilians and instigated peace but the bad part is that it reinforces that the gangs are now outside government authority," Juan says. "The police are only ornaments, the ones who take care of the neighbourhoods are the drug dealers.”

He elaborates: the people who work for the narcos are more feared than the police, because if they catch a thief then they'll execute him. Civilians thus enjoy low rates of petty crime, but for those enmeshed in the drug world, life can be precarious.

When asked about the shooting across from his house, Juan shrugs. “It’s not rare. Of course I’m afraid. But we have to learn to live with it and keep going.”

Buchons

In 2012, the Sinaloa cartel made something in the region of $3bn, according to estimates by the Congressional Research Service. The capture of El Chapo, and the splintering of the cartel's power base, has likely dented this figure, but the Sinaloan capital's economy is still buttressed by a lot of ill-gotten, untaxed money.

Some of this is evident in the palatial homes we drive past on our way into the city, displays of wealth that are a key element of 'buchon' – the culture of conspicuous consumption made fashionable by the city's cartel members (one theory is the name comes from Buchanan Scotch whisky, the preferred drink of the narcos).

Those in the more legitimate economy tap this narco culture with an entrepreneurial spirit. On a busy street in the city centre, an open-fronted shop called La Raza – which loosely translates as ‘the people’ – sells a wealth of knock-off designer goods, offering ordinary citizens a way to ape buchon.

Down the street, a boutique called Victoria is selling a tight brown leather skirt and shiny, Fendi-esque top for 820 pesos (about £35). The ensemble is worn by a mannequin with a tiny body, long legs and exaggerated backside – proportions immediately recognisable to any Keeping Up With the Kardashians fan – that is popular among buchonas. It's a look echoed around town in billboard ads around town for layaway plastic surgery.

Narco money has even seeped into the churches. When he was arrested, Ovidio Guzmán Lopez was wearing a pendant of Jesús Malverde, a Robin Hood figure of the early 1900s who was hanged by the authorities and is often called the patron saint of narcos, and the lost.

A chapel dedicated to him, to the southeast of the city centre, is abutted by train tracks at the back and a busy street in front. A handful of street vendors sit on concrete benches in front of the shrine, next to tin booths loaded with amulets, candles, statuettes of Malverde, the Virgin of Guadalupe and El Chapo. They are awaiting pilgrims – tourists, residents, and narcos.

Among the trinkets are the glamourised trappings of the narco life – a gold-plated AK47 necklace and gangster-style baseball caps with 'SINALOA' written in gothic letters, alongside more conventional religious items. Inside the shrine, which is open to the street front and the vendors, a small electric fan fights the stifling heat. Mario Gonzales, one of the vendors, say that the El Chapo statuettes are among the best-sellers.

“A lot of people come to buy these, even people from the US,” he says. “He’s a guy that who has helped a lot of people, especially in the highlands [of Sinaloa] and that’s why a lot of people love him very much.”

An older man in a loose, purple bowling shirt, who gives his name as Francisco, lights two candles with a paper spill, which he then struggles to put out, before taking the offerings to a glass-fronted shrine. Outside, trains clatter past rhythmically.

Francisco is from Sonora, the state to the north that separates Sinaloa from the Arizona border, but says he’s been in Culiacán for about 60 years. He’s 82 now. “When I came here for the first time it was a very tranquil city, very relaxed and small. As it started developing I started seeing drug cartels arriving, that’s something that the government has never been able to control.”

His faith is different to that of the narcos, he says, adding that he hasn’t been affected by the violence directly. “No, no, no. Of course, you hear about things happening, but the less you ask, the less you get involved with what’s going on the better and we can live peacefully.” When asked if he believes Malverde is protecting him, he replies: “That’s my faith.”

The chapel is not big – no more than 3,000 square feet – but it is jammed with plaques proffering thanks for Malverde’s purported, miraculous help. It sees a steady stream of the faithful, says Gonzales, the vendor. It had tailed off following the October attack but now it’s back to its former popularity.

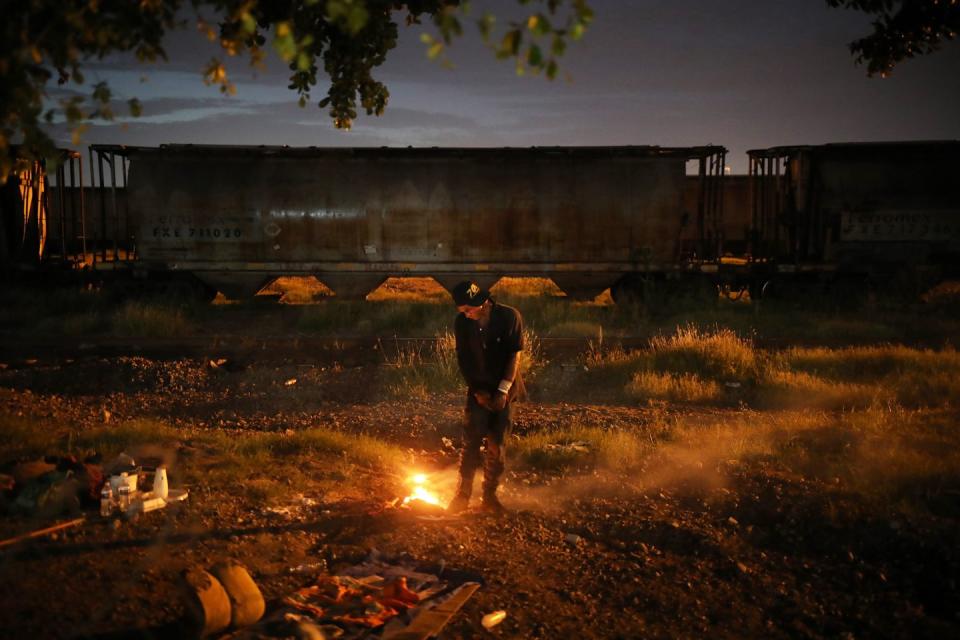

Behind the concrete structure, with its corrugated iron roof, a patch of scrap land abuts the train tracks. Here, addicts get high around bonfires fed with trash. One, who gives his name as Rogelio, says he fled to the city from a village in the surrounding countryside when he was nine, after his father killed his mother.

Despite being a user of the drug lords’ main products, he says, in his thick Northern Mexican accent, that there is a street morality at play and addicts like him can be punished even for minor transgressions: “If I’m outside after 10pm and someone from the cartel gets me, I could get in a lot of trouble.”

Like Malverde, the cartels cultivate a Robin Hood mythos – violent, yes, but on the side of the poor against a corrupt state. As well as their influence over fashion, lifestyle and religion in Northern Mexico, tales of their munificence abound, from parks and highways they've funded to the food parcels they passed out at the peak of the coronavirus crisis, which were stamped with El Chapo's face. But the narcos are not on the side of the ordinary person, says Ibarra, the academic. He argues that the popular notion of the narco as a man of the people is a smokescreen, likely perpetuated by the groups themselves.

“It’s a lie that they pay for things,” he says. “They pay ‘tax’ to the governor, the generals, the police,” he says, in the form of bribes, but the idea that they’re buying public loyalty through gifts and infrastructure projects for the poor is “a myth, it’s false, the image of the Robin Hood narco.

“There is no narco philanthropy. They sometimes build roads but they’re for their own use. But they are not philanthropists. The people know very well. I don’t know why worldwide some media share that story.”

The cancer

Graciela Dominguez Nava, a first term congresswoman and a member of AMLO’s Morena party, pleads for patience with the new president’s tactics, which include the formation of a new National Guard. The scale of the problem, she says, is almost overwhelming for the authorities.

“I believe that López Obrador is setting up the foundations for a new way of ruling the country, she says. “I agree that the levels of violence that were unfolding on the decades past to now are not going to be solved in his six years but I believe he’s setting up a new way of moving the country and some of these results might be faster than you think.”

But for those on the front lines, the violence – which can be both insidious and quotidian, and also wrenchingly explosive, like it was on Black Thursday – seems intractable.

“What hope could a person who’s diagnosed with cancer have? Could you tell him that he has no cancer? I don’t mean that’s it’s incurable but weaker remedies are not the solution,” says Ibarra.

“We are living in a special crisis of modern society. Everywhere you put your eyes is a big problem. If you want to solve the problem of the Sinaloa drug cartel with an isolated solution it won’t be successful. Fortunately [for those living in] Sinaloa, the narco republic and the civil republic coexist mostly peacefully.”

Miss Elegance

As is so often the case, it is the women in Culiacán who bear the brunt of the narcos’ violence. In her neat, concrete house in a working-class neighbourhood to the north of the city, Leslie, a striking young woman recounts the incident that changed the course of her life forever.

Eight years ago, then a schoolgirl, she was sitting in a car with her friends when, in an apparent case of mistaken identity she was shot in the head by a soldier, part of a patrol pursuing a white Humvee transporting suspected narcos.

Her friend's white pickup truck was spotted, mistaken for the fleeing Humvee, and the soldier opened fire. The driver panicked and sped off, causing the army patrol to give chase.

When the vehicle eventually halted Leslie was found slumped in her seat, the bullet having passed through her head. It entered her skull on the upper left side and exited on the right, putting her in a coma but, miraculously, not killing her. Since then she has had three operations and is still wheelchair-bound.

Before the incident she said wanted to be a news anchor but has accepted that that dream is now out of her grasp. Instead, she has a degree in sociology and is looking for work, although in the two years since she graduated it hasn’t been forthcoming, a consequence of Mexican society’s attitude towards people with disabilities, she says.

In the meantime, she gives speeches about her experience and how she came out the other side as a positive person, and last year was Sinaloa’s representative in a national beauty contest for people with disabilities. While she didn’t win, she was awarded the title of 'Miss Elegance'.

“It’s very sad to say it but [the narco state] is the reality of how we live. Daily, it’s business as usual. Every part of society is surrounded by it.”

Despite the random act that left her paralysed from the waist down, she insists that those who stay away from the drug trade won’t be affected by the violence.

“If you don’t get involved in it nothing will happen to you. Some people say the narcos help some people, when there are floods or natural disasters, I’ve never seen it but that’s what I’ve heard. It’s intertwined in society.”

The bloodhounds

But for others, no matter how much they keep their heads down, the violence of the narco world finds them.

Disappearances are a brutal tactic and have been used by authoritarian regimes and criminal groups throughout Latin America as a particularly harsh form of violence, one which is perpetrated on the whole family. The pain of never knowing, victims say, means never having closure.

Maria Isabel Cruz Bernal heads Subuesos Guerras – 'bloodhound warriors' – a group dedicated to finding those who have been disappeared by the cartels. She is searching for her son, Yosimar Garcia, a policeman who was due to get married three months after he was disappeared.

The group's headquarters are housed in a semidetached house in a lower-middle class district, which also happened to be Yosimar’s old home. In the entranceway to the house are piled half a dozen pitted, well-used spades and some sifting trays – the tools of the trade for these women, who now spend their days excavating possible unmarked graves.

An A4 print-out is pinned to the wall, featuring three photos of Yosimar, along with the phrase ,“God makes the impossible possible". Isabel’s planner, which sits atop an oversized, jumbled desk, features a sticker which asks, in large letters, the simple question: Donde estan? – where are they?

In a calm, clear voice she recounts the period almost three years ago in which her life changed irrecoverably. “It all started one day when my son was working. They received a call from the army saying that they had been in an ambush – a bomb had been thrown at them and they were asking if someone could go and help them over the radio.

“They attended the call, they went to rescue them and when they arrived the army – some of them were missing legs, some had their intestines out, so they took them to the hospital.

“Two months later some armed people, some of them looked like soldiers and some were just wearing black, came to the house Yosimar was living in with his brother. They knocked on the door and asked for him. He didn’t want to come out, but they saw him through the window. So he went upstairs to get a t-shirt and then went out to them. They hit him in his ribs with the butt of a rifle and when he bent down, they handcuffed him and took him away, and that was the last anyone saw of him.”

She has been threatened, she says, by the groups whose work she undermines, but her agony has taken away her capacity for worry. “They took away the fear from me the day they took him. I’m missing the most important thing a mother can miss so there’s no time for me to get tired, give up or get sick until I find him.”

Isabel says the incident, and her subsequent work searching for the desparacidos – the missing – has cost her her faith. “I used to be the type of person who lit candles, until I realised I was just making the candlemaker rich.”

Isabel says the authorities play down the numbers. “They say that three or four people go missing every day, but our numbers are more like eight or ten.”

And so her work continues. Throughout our conversation she speaks of Yosimar in the past tense, convinced he’s already dead. Given the violence endemic in Culiacán, and the ruthlessness of those who took him, it is a fair assumption and one which allows her to put the uncertainty of not knowing out of her mind.

She says she’ll hang up her shovel when she finally locates her son, or most likely his remains. “When Yosimar is found I don’t think I’ll continue [to run Sabuesos Guerras]. I’ll retire to grieve.”

She says that the events of Black Thursday were a “display” and a reminder of which group holds the real power in Culiacán, and how the narcos remain above the law.

“Ovidio [Guzman] disappeared for a few hours and they found him right away. We’ve been fighting for [over] two years for our disappeared and nobody does anything.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance