National pandemic exit plan modelling doesn’t examine what happens after restrictions are eased

National cabinet’s pandemic exit strategy only considered modelling for the “transition” phase over the next six months, with the Doherty Institute yet to consider how relaxed restrictions will affect transmission in the community.

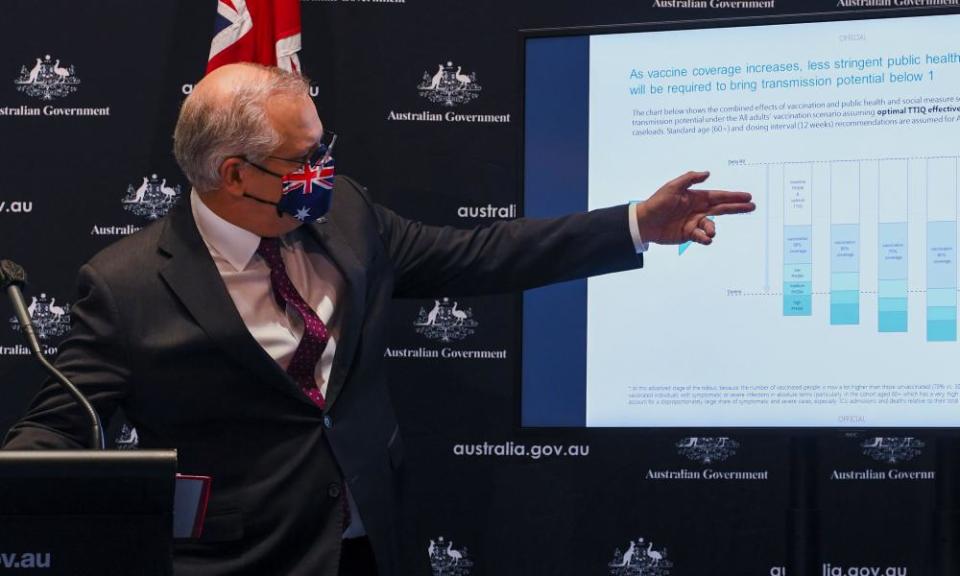

The federal government on Tuesday released the modelling that underpinned the updated four-phase roadmap announced on Friday, with the research highlighting the need for a “strategic shift” to targeting young adults who were most likely to transmit the virus.

But the Doherty Institute’s professor of epidemiology, Jodie McVernon, said the centre had only considered the best strategy for the next six months, with the external environment too uncertain to consider anything beyond that point.

The third step of the plan signed off by federal, state and territory leaders – which includes exempting vaccinated residents from domestic restrictions, removing caps on returning vaccinated Australians and lifting restrictions on outbound travel – was agreed to without any modelling to show the consequences of this “consolidation” phase, which would be triggered when 80% of the adult population was vaccinated.

The fourth and final phase of the plan, dubbed “post-vaccination” that outlines a return to normal scenario, has also been endorsed without any modelling.

“The reason we stopped when we did is six months is a long time in this pandemic [and] if you look at the past six months, a lot has changed,” McVernon said.

“What we’ve evaluated and assessed is, is how far we think we could get with 80% vaccine coverage based on the current circulating strains and assuming the population stays on board with behavioural measures and other things. Beyond that, we think it’s just too hard to know what will be happening in the external context for us to be able to really meaningfully inform that assessment.”

McVernon said the institute would consider how the relaxing of restrictions would work in its next phase of modelling – but further work and consultation was needed.

The Grattan Institute, which released its own modelling on an 80% vaccination rate last week, said the national cabinet plan appeared to be “risky” based on the assumptions in the Doherty modelling.

“The Doherty modelling shows that isolating and quarantining will be critical to control Covid at 70% or 80%, and if they fail we’ll need lockdowns,” the Grattan Institute’s Tom Crowley told the Guardian.

“But phase C of the government’s plan undermines isolating, quarantining and lockdowns all at once by exempting vaccinated people, even though they can still spread Covid.”

This would mean that both the first line of defence – testing, tracing, isolating and quarantine – and the last line of defence – lockdowns – would be undermined.

“That’s a recipe for a bad outcome according to the government’s own modelling,” Crowley said.

The modelling, which underpinned national cabinet’s plan for Australia to live with the virus, also shows that until vaccination rates reach 70% any outbreaks will likely see “rapid and uncontrolled” growth, leading to a significant number of deaths and severe cases.

To combat the challenge of the “aggressive Delta strain”, the Doherty Institute advocates an increased uptake of the AstraZeneca vaccine for those over 40, saying its protection is comparable to Pfizer, with one dose being 69% effective against death and two doses 90% effective.

The Doherty report outlines that once the vaccination coverage reaches 70% and 80%, the rate of severe infections is reduced, but under an “uncontrolled outbreak” scenario, between 1,300 and 2,000 people would still die from 10,000 to 20,000 severe infections within six months.

If low-level restrictions were ongoing – such as capacity limits and social distancing – then a 70% vaccination rate would see as few as 16 deaths within six months, as long as the testing, tracing, isolating and quarantine (TTIQ) regime was “optimal”.

If the TTIQ system is only partially effective, then the rate of deaths would be more than 100 times worse, with 1,908 deaths from almost 400,000 cases, the modelling says.

McVernon said the modelling showed the critical importance of ongoing public health measures to complement a vaccinated population.

“If we can keep some social measures on, if we can maintain that public health capacity and if we can allow the synergy of those interventions to work together, then we can potentially reduce adverse outcomes a hundredfold,” McVernon said.

She also said that while the current government strategy to focus on vaccinating older and vulnerable groups was the right one, now that vaccine supplies were increasing the focus should shift to young people, who were the “peak transmitters” of the virus.

“Looking at the best strategic use in moving forward our recommendation is to pursue a strategy that draws on the direct protection that’s already been achieved but amplifies it by focusing now on transmission,” McVernon said.

Under an “all adults” vaccination focus, the number of symptomatic infections would number 393,516 in a six-month period, compared to 617,292 under an “oldest first” strategy.

Of these infections, deaths would be 1,984 and 3,564 respectively, however, the modelling says that these figures are likely overstated given the scenario assumes minimal density and capacity restrictions.

McVernon also said that while young adults were most likely to transmit the disease, the best way to protect children was to vaccinate their parents, with the vaccination of children only having a “modest” impact on transmission rates.

“By vaccinating parents, you protect children,” she said.

“I am a parent. I was a paediatrician before I was a public health doctor.

“Children are very important. So a strategy that protects them as well as elders in the population and the working-age people we believe to be the best strategy at this time.”

The research finds that the vaccine coverage is a “continuum” – every increase in the vaccination rate reduces virus transmission and negative health outcomes.

Until there are high vaccination rates, the best strategy is to continue with a suppression approach to “lock down early and hard” when there is an outbreak to limit the duration and costs of lockdowns, the modelling says.

The prime minister, Scott Morrison, said the government had changed its approach to the virus after the emergence of the Delta variant.

While Morrison initially commended the New South Wales government for not going into a hard lockdown over the state’s outbreak, he said on Tuesday that the tools that had previously worked had been “blunted” by the Delta strain.

“That means we have had to adjust our response, and so the reality of short, hopefully, but strong lockdowns to ensure that the Delta strain does not get away from us … is now our first response,” Morrison said.

“When the circumstances change you must change with them.”

He also rejected suggestions that the NSW government could emerge early from the current lockdown, saying it needed to bring down the number of cases in the community “to a level where they can be suppressed and contained”.

“That is the goal the NSW government is working towards.”

Related: Most Australians comfortable with vaccination passports for domestic travel and venues, poll reveals

He said the Doherty modelling was not applicable to “breaking out” of an existing lockdown, after the NSW premier, Gladys Berejiklian, flagged the easing of restrictions once the vaccination rate reached 50%.

The modelling suggests that rapid spread and high caseloads would still be expected at that level, with more than 1m symptomatic infections nationwide within six months. This is based on modelling with baseline restrictions and “partial” TTIQ effectiveness.

On Tuesday, the treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, also gave an update on the economic cost of lockdowns, saying swift action – like what had been achieved in Queensland, South Australia and Victoria – was the best approach.

“If they don’t, we see lengthier and more severe lockdowns, which have a much more significant economic cost,” he said.

He said Treasury estimates suggested that with a 50% vaccination rate, the economic cost of an outbreak was $570m per week, reducing to $200m a week once the vaccination rate reached 70%, and $140m a week at 80%.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance