What really happened to Edson Da Costa?

They were cruising at speed down Tollgate Road, the stereo turned high. They all knew they shouldn’t be there, not at this time, not after dark. If you’re from London’s Stratford, showing up in nearby Beckton carried its risks.

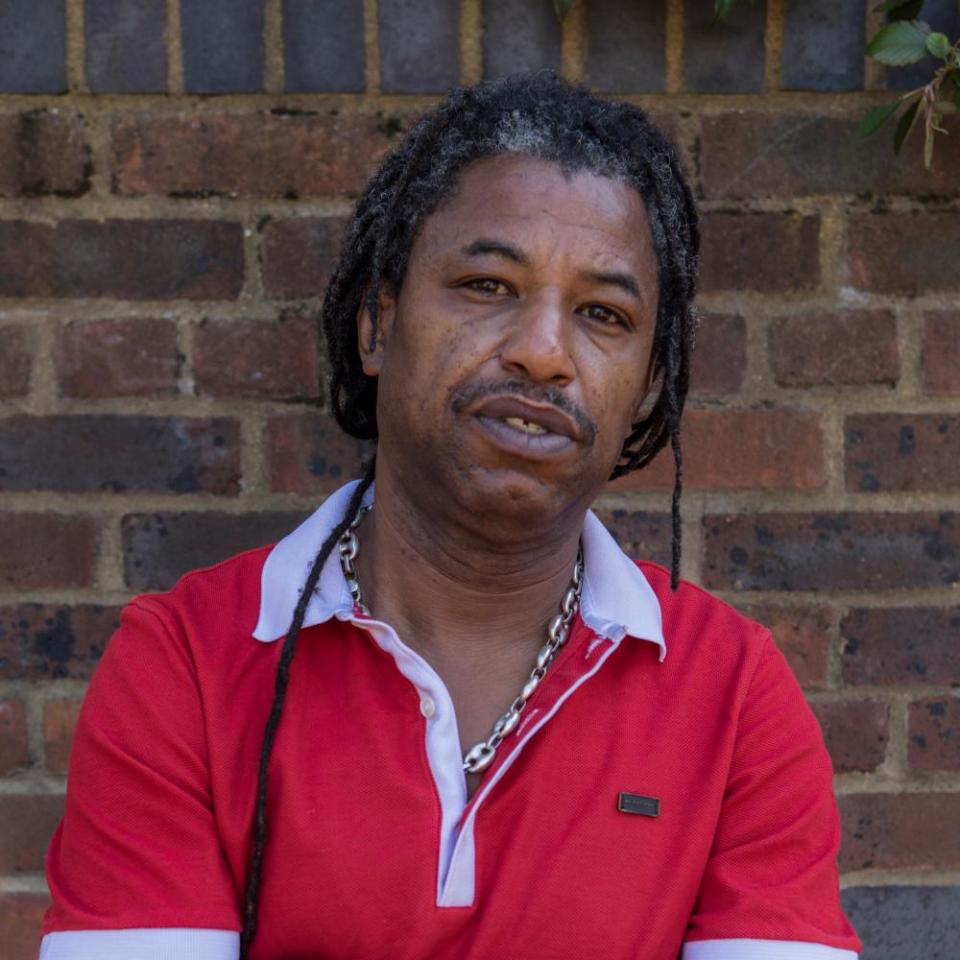

Jussara Gomes was driving, a fast-talking 23-year-old with an infectious laugh. Beside her, in the passenger seat of the black A-class Mercedes, was Edir Da Costa, known as Edson, a 25-year-old father and car mechanic, swaying exuberantly to hip-hop.

Behind, sat Claude Greenaway. They’d been friends since primary school after Da Costa arrived in London from Portugal.

Shortly before 10pm a Subaru pulled alongside. Inside were five men, some were staring. Gomes felt panic. But as flashing blue lights flooded the Mercedes, she relaxed.

At 9.59pm and 28 seconds on 15 June 2017, closed circuit television tracked her turning into the Woodcocks estate and pulling over. An unmarked police car containing five plainclothes officers drew up beside.

Gomes said she felt “chilled” and flashed a smile at the police. Greenaway was asked to step outside, then Da Costa.

Gomes, still in the car, heard talking that escalated abruptly into shouts, the sound of a scuffle. Leaving the Mercedes, time seemed to freeze. Da Costa was on the ground, police officers on top of him. She remembers his eyes rolling to the back of his head, his body motionless.

Increased scrutiny on deaths following police contact have sparked international uproar, reframed the debate on structural racism and police brutality, and electrified the Black Lives Matter movement.

In London, the cases of Mark Duggan, who was shot and killed in 2011, and Rashan Charles, 20, who died in 2017 after being restrained by officers in Hackney continue to resonate.

Less known is the 25-year-old who died following a traffic stop in the capital three years ago. According to witnesses Da Costa was pinned face down on a road by four officers. Witnesses alleged officers put pressure on his neck. Onlookers challenged the police, shouting that a man was dying. There were complications getting medical help. Da Costa, who was unarmed, lost consciousness in the street.

And Da Costa had much to live for. A devoted dad, the 25-year-old was a skilled car mechanic with plans to set up a refurbishment garage.

Da Costa’s family have long given up expecting more answers to what happened that night.

Now an Observer investigation into Da Costa’s death featuring fresh interviews with witnesses and family, transcripts of unreleased video footage and police interviews, along with the unpublished 124-page official inquiry into his death, appears to raise fresh questions.

Why was the Mercedes stopped in the first place? A question that appears a mystery. The officers belonged to Operation Viper, which tackles gun crime. Viper briefings, according to the unpublished Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) report from 2018, had never mentioned Da Costa, Gomes, Greenaway or their car.

This is about a stop and search in which someone ended up in a coffin. Why were they targeted in the first place?

Jair Tavares

But the report does identify a black Ford Focus seen by the officers near Woodcocks estate minutes before they pulled over Gomes, its passenger running away, hunched over as if concealing “a weapon”.

The Focus appears crucial because officers say they stopped the Mercedes partly because its “front seat passenger looked similar” to the suspect in the Focus – and may have been dangerous. Yet IOPC investigators found no reference to the Focus in stop and search records. They then examined Viper intelligence requests. According to the report, the only black vehicle targeted that day was an Audi. There was one Ford, but it was grey or silver.

A central objective of Viper is intelligence acquisition. Why was a car in which a man ran from police holding a suspected weapon not entered into the system? And who was the “weapon-carrying” man? One officer described him wearing a black T-shirt and black baseball cap. Da Costa, said Gomes, was sporting a blue Ralph Lauren tracksuit. “This is about a stop and search in which someone ended up in a coffin. Why were they targeted in the first place?” said Jair Tavares, Costa’s cousin.

The police also point out the Mercedes was a hire car, arguing that gangs frequently used rentals. But IOPC investigators also identified other potential reasons why the car was stopped. The most senior plainclothes officer involved told investigators the Mercedes was targeted because a young black woman was driving. He “stated they could see the driver was a black woman in her early 20s, which ‘did not seem normal’ as the vehicle was worth at least £30,000”. “It is not clear why [he] did not find this normal and he does not explain this any further in his accounts,” states the IOPC report.

And what about race?

Stop and search statistics for four of the plainclothes officers between May 2016 and January 2018 were analysed by investigators. It shows that one of the officers made 13 stops of which 69% were against black people. Another made 51 stops with over half targeting black individuals. A third made 67 stops of which 42% were black, roughly the same breakdown as the fourth. The IOPC concluded discrimination was not a factor for the stop. Da Costa’s family feel differently.

“You alright fella?” an officer asked Da Costa as they stood beside the police vehicle. “Hmmm,” he replied, according to interview transcripts. Unbeknown to officers, Da Costa had swallowed 88 wraps of cocaine and heroin and was potentially facing life in prison. He made a run for it, before Greenaway described him being “rugby tackled”. According to witnesses four officers pinned him face down on the ground.

Quickly, the commotion rippled throughout the estate. One witness described a “pile up” of officers on Da Costa. David O’Brien, who lives 10 metres from the scene, described police on his back, “putting a lot of weight on him”.

From the IOPC report a catalogue of errors appear to have ensued, including a decision to subdue Da Costa further. Believing his colleagues were “struggling to restrain” Da Costa, CS spray was aimed into his face from, according to two witnesses, around 6cm away. Guidance stipulates CS spray shouldn’t be used less than one metre from the target. The officer responsible “refused to specify the distance” to investigators, states the report.

Soon after, Gomes said she saw foam bubbling from Da Costa’s mouth. Around this time officers saw “small individual wraps” of drugs on the ground beside his face. The IOPC report states four of them suspected Da Costa had swallowed drugs “some time before” his condition deteriorated. A 28-page medical report into the case, from intensive care expert professor Jerry Nolan, believes Da Costa could have been saved if officers had climbed off and made him spit out the wraps.

Someone suspected of ingesting drugs should, according to police guidance, be taken directly to hospital. Da Costa, though, was handcuffed behind his back, still face down. Again this appears to contravene national guidance, increasing the risk of positional asphyxia, when someone struggles to breathe.

Officers, adds the report, still thought he was resisting arrest. An expert report suggests that may constitute a fundamental misreading of the situation. Da Costa was likely panicking, frantically fighting for breath. “Struggling movements might have reflected airway obstruction rather than efforts to escape,” said Nolan.

More apparent mistakes are articulated in the report. Officers are told that choking can be recognised by coughing and difficulty speaking. A witness told investigators Da Costa “tried unsuccessfully to speak” while the lead officer heard him cough but “did not believe it was a sign he was choking”. Investigators would later learn the officer had not attended life support training since 2012, which he was meant to refresh annually. Da Costa should have been “repeatedly asked” if he was choking but apparently wasn’t, the watchdog found.

The mobile phone starts recording the scene at 10.03pm and 56 seconds. Shot by a neighbour, the grainy footage captures Da Costa handcuffed, lying still on the road. Officers roll him on to his side and remove his handcuffs.

At 10.04pm and 35 seconds a member of the public shouts: “He’s not all right, he’s not all right”. Nolan agrees, his expert view is that Da Costa has, at this stage, likely stopped breathing. Around now it is reported that an officer notices Da Costa “yawning”, interpreting the behaviour as a sign of life. The opposite is suggested. Medical analysis indicates these as “agonal breaths”, the gasps of someone suffering cardiac arrest.

Armed officers arrive at 10.05pm and 23 seconds. A body-worn camera records them examining Da Costa and concluding he is “not breathing”.

At 10.05pm and 39 seconds, police radio transmission data confirms a plainclothes officer requesting an ambulance. Subsequent statements from him appear to offer no explanation why he waited until armed colleagues arrived. They also state he told ambulance officials that Da Costa was unconscious. In fact, he informed the ambulance service that Da Costa was “responsive” and “conscious”. Not once, but twice. Accordingly the call was not graded as an emergency.

Worse followed. According to the timeline of footage gathered by IOPC investigators, by mistake the police control room guided the ambulance towards Woodcote in Surrey, 70 miles from the Woodcocks estate where Da Costa was lying.

At 10.06pm and 56 seconds, footage shows a firearms officer shining a torch into Da Costa face. His eyes stare back unblinking. Foam is spilling from his mouth, mucus from his nose.

Even now, it appears he is deemed a threat. According to the report one officer is heard claiming Da Costa’s lifelessness could be a ruse. “Not sure if it’s all an act,” he says.

At 10.07pm and 13 seconds, another officer repeats the suspicion Da Costa might be trying to catch them off guard. “Your sole purpose in life mate is to keep an eye on these hands,” he tells a colleague.

At 10.07pm and 20 seconds, a firearms officer demands a medic and asks plainclothes colleagues: “How long has he been like this?” The answer is inaccurate. “Literally 30 seconds before you guys got here.”

Soon after, officers begin CPR on Da Costa. Onlookers are overheard fearing the worst. One bystander, at 10.08pm and 30 seconds, says: “The guy’s not even moving, how long does it take to call an ambulance?”

At 10.13pm and 18 seconds another bystander says: “There’s no point saving him now, he’s fucking dead.”

Ten seconds later O’Brien tells officers the damage is done. “He’s already dead. I told you to call an ambulance.” Another onlooker says he told officers to call an ambulance 15 minutes earlier.

Finally, at 10.14pm and 11 seconds, the ambulance call is upgraded to requiring immediate response.

Four minutes later the first paramedic arrives and at 10.40pm Da Costa is taken to nearby Newham Hospital where doctors discover a large plastic bag is completely obstructing his throat.

Those who arrived at hospital the following day were shocked. An enormous swelling contorted Da Costa’s neck. Towels were wedged under his jaw to stop his head lolling forward. “I cannot forget what I saw,” said his father Ginario.

For six days his family maintained a vigil before his life support was turned off.

My son died for no reason. Every day I wake up and that is how I feel

Ginario Da Costa

His death prompted riots, officers repelling demonstrators from Stratford police station. Ginario appealed for calm. “I was broken,” he said. Da Costa’s mother, Manuela Araujo, was similarly crushed. Immediately, she made plans to travel from Portugal to attend her son’s funeral. Having no EU passport, Araujo applied for a visa. The Home Office rejected her application. Several days later she drowned herself in a Porto river. “The thought of never being able to see him again was too much,” said Ginario.

Da Costa’s father clung on to the prospect of justice. A quiet, thoughtful man he had arrived from Portugal when his son was four because of better opportunities, better schooling, the UK’s reputed fairness.

He was confident the IOPC inquiry and inquest would uncover the truth. When the police watchdog began investigating he felt vindicated.

Then, on 30 October 2018, the IOPC released its findings that the force used on Da Costa was “necessary and proportionate”. The family queried the timing because of the impending inquest but it was considered it wouldn’t prejudice it and was to rectify “inaccurate and misleading” rumours surrounding the death.

The press statement carried other ramifications. Despite questions over why the Mercedes was targeted, it said Da Costa was stopped by officers “tackling gang related activity”. At a stroke Da Costa was implicated in far more serious crime than dealing drugs.

Even so, Ginario believed the May 2019 inquest would deliver. His hopes took a precipitous dive when the coroner asked each juror to reveal if they or their family were “involved in any campaign groups such as Black Lives Matter”. It is the only time the charity Inquest can recollect BLM membership being an issue. When asked why she cited the group, the coroner said she could not comment on individual cases outside of court.

Extra security was present at the hearings. The family say they felt intimidated by the sizeable police presence. Tavares says it felt they were being spied on. “There were different types of police outside, watching us. We felt monitored,” he said. Other friends and family who supported Black Lives Matter feel like their attendance at the inquest put them under the spotlight.

More angst would follow. Summing up, the coroner told jurors there was no legal or factual basis for reaching a conclusion critical of the police.

Ultimately, a verdict of “misadventure” was recorded by nine jurors to two. Deborah Coles, director of the charity Inquest, said the findings were “hard to reconcile with the evidence”.

The family is now demanding a fresh inquest.

Three weeks after the inquest’s conclusion, the coroner wrote to the Met outlining seven significant “matters of concern” relating to Da Costa. Issues included failure to monitor his condition, ignorance over the dangers of swallowing plastic bags and use of CS spray.

Much continues to torment the family, particularly “the neck” issue. When the IOPC began its investigation into Da Costa, officers were alleged to have restrained him “round his neck using techniques that were not appropriate”. Although this was found not to be the case, the family remain unconvinced.

Several witnesses in the IOPC report offer testimony apparently supporting this, including one who said an officer “appeared to be either choking him or trying to get something out of his throat using a pumping motion”.

Gomes, shortly after the incident, told the Observer she thought officers applied pressure on her friend’s neck. The postmortem found no neck injuries suggesting excessive force. Written statements from all five officers said they did not touch Da Costa’s neck. The IOPC concluded the officers had no case to answer.

More setbacks hit Ginario. The latest came last Friday night when he learned the one officer due to face IOPC misconduct proceedings over his son’s death left the force last year before disciplinary proceedings began.

Ginario said he was having trouble sleeping. “My son died for no reason. Every day I wake up and that is how I feel.”

So far, Da Costa’s death has prompted three procedural improvements in policing. A Met statement said it took such tragedies “extremely seriously and looked to learn from them”. Investigators concluded the officers had no case to answer over the “medical intervention” and checks they gave Da Costa.

In addition, the IOPC found no excessive force was used and there was no evidence of discriminatory behaviour.

Da Costa’s family disagree, alleging a “smear campaign” was orchestrated by the police to depict Da Costa as a gangster.

No one knows why Da Costa, who never drank alcohol until 18, was carrying 88 wraps of class A drugs that night. When stopped, he and his two friends were travelling to an Asda to buy drinks for a birthday party.

Ginario cannot imagine celebrating again. “Not until there is justice.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance