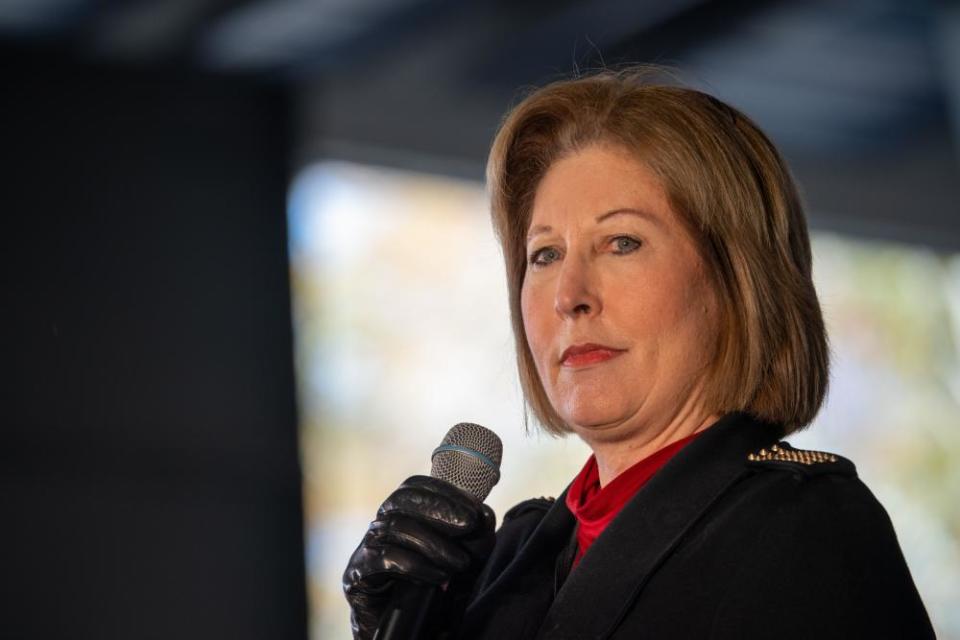

Revealed: how Sidney Powell could be disbarred for lying in court for Trump

Sidney Powell, the former lawyer for Donald Trump who filed lawsuits across America for the former president, hoping to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, has on several occasions represented to federal courts that people were co-counsel or plaintiffs in her cases without seeking their permission to do so, the Guardian has learned.

Some of these individuals say that they only found out that Powell had named them once the cases were already filed.

During this same period of time, Powell also named several other lawyers – with their permission in those instances – as co-counsel in her election-related cases, despite the fact that they played virtually no role whatsoever in bringing or litigating those cases.

Both Powell’s naming of other people as plaintiffs or co-counsel without their consent and representing that other attorneys were central to her cases when, in fact, their roles were nominal or nonexistent, constitute serious potential violations of the American Bar Association model rules for professional conduct, top legal ethicists told the Guardian.

Powell’s misrepresentations to the courts in those particular instances often aided fundraising for her nonprofit, Defending the Republic. Powell had told prospective donors that the attorneys were integral members of an “elite strike force” who had played outsized roles in her cases – when in fact they were barely involved if at all.

Powell did not respond to multiple requests for comment via phone, email, and over social media.

The State Bar of Texas is already investigating Powell for making other allegedly false and misleading statements to federal courts by propagating increasingly implausible conspiracy theories to federal courts that Joe Biden’s election as president of the United States was illegitimate.

The Texas bar held its first closed-door hearing regarding the allegations about Powell on 4 November. Investigations by state bar associations are ordinarily conducted behind closed doors and thus largely opaque to the public.

A federal grand jury has also been separately investigating Powell, Defending the Republic, as well as a political action committee that goes by the same name, for fundraising fraud, according to records reviewed by the Guardian.

Among those who have alleged that Powell falsely named them as co-counsel is attorney Linn Wood, who brought and litigated with Powell many of her lawsuits attempting to overturn the results of the election with her, including in the hotly contested state of Michigan.

The Michigan case was a futile attempt by Powell to erase Joe Biden’s victory in that state and name Trump as the winner. On 25 August, federal district court Judge Linda Parker, of Michigan, sanctioned Powell and nine other attorneys who worked with her for having engaged in “a historic and profound abuse of the judicial process” in bringing the case in the first place. Powell’s claims of election fraud, Parker asserted, had no basis in law and were solely based on “speculation, conjecture, and unwarranted suspicion”.

Parker further concluded that the conduct of Powell, Wood, and the eight other attorneys who they worked with, warranted a “referral for investigation and possible suspension or disbarment to the appropriate disciplinary authority for each state … in which each attorney is admitted”.

Wood told the court in the Michigan case that Powell had wrongly named him as one of her co-counsel in the Michigan case. During a hearing in the case to determine whether to sanction Wood, his defense largely rested on his claim that he had not been involved in the case at all. Powell, Wood told the court, had put his name on the lawsuit without her even telling him.

Wood said: “I do not specifically recall being asked about the Michigan complaint … In this case obviously my name was included. My experience or my skills apparently were never needed, so I didn’t have any involvement with it.”

Wood’s attorney, Paul Stablein, was also categorical in asserting that his client had nothing to do with the case, telling the Guardian in an interview: “He didn’t draft the complaint. He didn’t sign it. He did not authorize anyone to put his name on it.”

Powell has denied she would have ever named Wood as a co-counsel without Wood’s permission.

But other people have since come forward to say that Powell has said that they were named as plaintiffs or lawyers in her election-related cases without their permission.

In a Wisconsin voting case, a former Republican candidate for Congress, Derrick Van Orden, said he only learned after the fact that he had been named as a plaintiff in one of Powell’s cases.

“I learned through social media today that my name was included in a lawsuit without my permission,” Van Orden said in a statement he posted on Twitter, “To be clear, I am not involved in the lawsuit seeking to overturn the election in Wisconsin.”

I learned through social media today that my name was included in a lawsuit without my permission. To be clear, I am not involved in the lawsuit seeking to overturn the election in Wisconsin.

— Derrick Van Orden (@derrickvanorden) December 1, 2020

Jason Shepherd, the Republican chairman of Georgia’s Cobb county, was similarly listed as a plaintiff in a Georgia election case without his approval.

In a 26 November 2020 statement, Shepherd said he had been talking to an associate of Powell’s prior to the case’s filing about the “Cobb GOP being a plaintiff” but said he first “needed more information to at least make sure the executive officers were in agreeing to us being a party in the suit”. The Cobb County Republican party later agreed to remain plaintiffs in the case instead of withdrawing.

Leslie Levin, a professor at the University of Connecticut Law School, said in an interview: “Misrepresentations to the court are very serious because lawyers are officers of the court. Bringing a lawsuit in someone’s name when they haven’t consented to being a party is a very serious misrepresentation and one for which a lawyer should expect to face serious discipline.”

Nora Freeman Engstrom, a law professor at Stanford University, says that Powell’s actions appear to violate Rule 3.3 of the ABA’s model rules of professional misconduct which hold that “a lawyer shall not knowingly … make a false statement of fact of law to a tribunal”.

Since election day last year, federal and state courts have dismissed more than 60 lawsuits alleging electoral fraud and irregularities by Powell, and other Trump allies.

Shortly after the election, Trump named Powell as a senior member of an “elite strike force” who would prove that Joe Biden only won the 2020 presidential race because the election was stolen from him. But Trump refused to pay her for her services. To remedy this, Powell set up a new nonprofit called Defending the Republic; its stated purpose is to “protect the integrity of elections in the United States”.

As a nonprofit, the group is allowed to raise unlimited amounts of “dark money” and donors are legally protected from the ordinary requirements to disclose their identities to the public. Powell warned supporters that for her to succeed, “millions of dollars must be raised”.

Echoing Trump’s rhetoric, Powell told prospective donors that Defending the Republic had a vast team of experienced litigators.

Among the attorneys who Powell said made up this “taskforce” were Emily Newman, who had served Trump as the White House liaison to the Department of Health and Human Services and as a senior official with the Department of Homeland Security. Newman had been a founding board member of Defending the Republic.

But facing sanctions in the Michigan case, some of the attorneys attempted to distance themselves from having played much of a meaningful role in her litigation.

Newman’s attorney told Parker, the judge, that Newman had “not played a role in the drafting of the complaint … My client was a contract lawyer working from home who spent maybe five hours on this matter. She really wasn’t involved … Her role was de minimis.”

To have standing to file her Michigan case, Powell was initially unable to find a local attorney to be co-counsel on her case but eventually attorney Gregory Rohl agreed to help out.

But when Rohl was sanctioned by Parker and referred to the Michigan attorney disciplinary board for further investigation, his defense was that he, too, was barely involved in the case. He claimed that he only received a copy of “the already prepared” 830-page initial complaint at the last minute, reviewed it for “well over an hour”, while then “making no additions, decisions or corrections” to the original.

As with Newman, Parker, found that Rohl violated ethics rules by making little, if any, effort to verify the facts of the claims in Powell’s filings.

In sanctioning Rohl, the judge wrote that “the court finds it exceedingly difficult to believe that Rohl read an 830-page complaint in just ‘well over an hour’ on the day he filed it. So, Rohl’s argument in and of itself reveals sanctionable conduct.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance