The rise of America's deadly 'boogaloo' extremists – and how they captured social media

It was the evening of May 29, four days after the death of George Floyd, and the police had lost control of downtown Oakland. After months of lockdown, the diverse Californian city's once-vibrant main drag was suddenly full of billowing tear gas, burning debris and crowds of jubilant protesters building impromptu barricades.

A few blocks away, barely noticed amid the din of choppers and pyrotechnics, a terrorist attack had just been committed. The murder of US federal agent Dave Patrick Underwood in a drive-by shooting that night would spark national speculation that black nationalists or even one of Oakland's many street gangs might be to blame.

Two weeks later, however, authorities announced they had arrested Stephen Carrillo, a 32-year-old former airman who had driven 72 miles from the tiny mountain town of Ben Lomond. Carrillo had allegedly plotted with a friend he met through a Facebook group – part of a strange and predominantly online new extremist subculture known as "boogaloo".

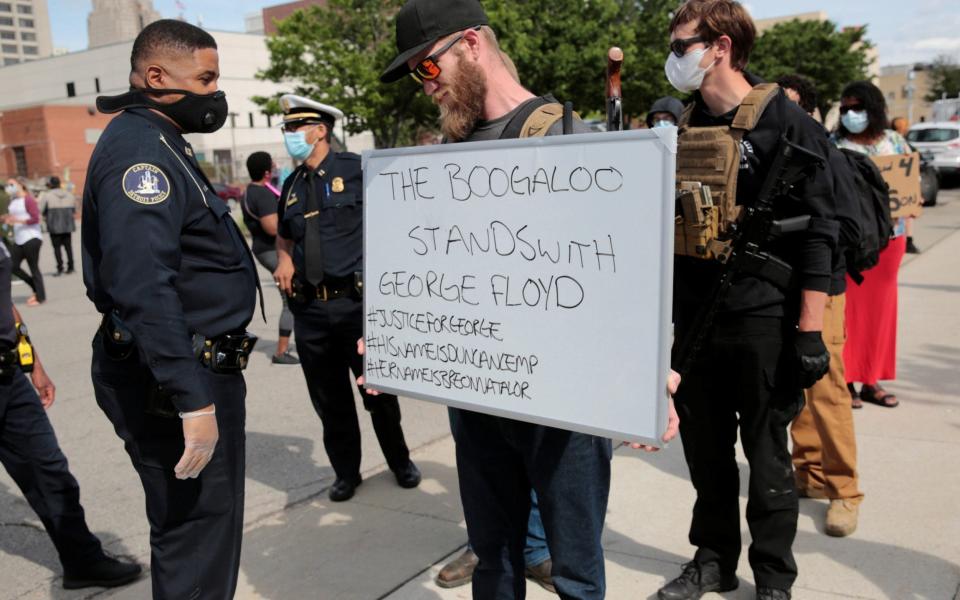

The boogaloo movement has now been linked to at least six attempted attacks across the US. Its members, with their distinctive Hawaiian shirts, igloo symbols and high-end firearms, have been spotted at many anti-lockdown and anti-police protests. On Tuesday, Facebook branded one boogaloo group as a "dangerous organisation", banning all support or praise of it.

But what precisely is a boogaloo?

"It's a meme that's been turned into a rallying cry," says Prof Julia DeCook, who studies online extremism at Loyala University in Chicago. "There's no real structure: some want to target minorities; some want to target law enforcement and government; some want to target both...

"They don't have a centralised set of goals that they're trying to achieve or anything like that. They're just coalescing around this pro-gun, anti-government ideology – and the more extreme factions call for a total societal collapse."

Civil war becomes an internet meme

Boogaloo is so fragmented and fluid, so lacking in clear leaders or spokespeople, that DeCook hesitates to even call it a "movement". Instead she describes it more as a "subculture", part of a wave of "informal" ideological networks made possible by digital technology.

Yet it also has deep roots. Chris Jones, a forensic reporter covering far-Right groups in America's impoverished Appalachian mountains, describes it as a "direct descendant" of the decades-old American militia movement, made famous by the 1993 Waco siege.

Militias have grown increasingly active since the election of Barack Obama in 2008, with heavily-armed groups such as the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters purporting to "keep the peace" at protests, marches, occupations and even the Mexican border. They have often been implicated in or accused of terror plots, vigilantism, voter intimidation and kidnapping, with a habit of threatening or predicting "civil war".

This is the literal meaning of "boogaloo": a second US civil war or nationwide uprising, which adherents tend to welcome, consider inevitable or actually hope to bring about. The term comes from the cheesy 1984 breakdancing film Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo, whose subtitle long ago became an internet meme used to signal a ridiculous or cynical sequel.

Its ghoulish new usage appears to have started around 2012, in the firearms section of the infamous anything-goes discussion site 4chan, according to the investigative website Bellingcat.

It soon jumped venues, spreading from white supremacists to disparate other groups who shared a hatred of the federal government and a conviction of imminent apocalypse: hardcore gun rights activists, traditional libertarians, survivalist "preppers" and even, reportedly, anti-racist anarchists.

"Unlike previous iterations of militia movements, [boogaloo] ideology comes out of an intersection of gaming culture, online Right-wing counterculture and a fascination with weapons and military hardware," says Prof Joel Beeson, who studies social media at West Virginia University and works with Jones on the Appalachia project.

Boogaloo first made headlines in January, when white supremacists using the term threatened to incite violence at a massive gun rights rally in Virginia. The rally ended peacefully, but boogaloo began to proliferate across Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Reddit and the chat service Discord, driven by both activists and opportunistic merchandisers.

Then came the pandemic, and then George Floyd. "For a community held together by an obsession with civil warfare, the idea of open battles... was incredibly alluring," says Jones. "Many thought this would be the beginning of said civil war."

The men in Hawaiian shirts

Ashley Dorelus, a freelance photographer, was live streaming nearby on the night of the Oakland shooting, and has since travelled to protests across the US filming a documentary. She says she has often seen strange people in Hawaiian shirts attempting to rile up crowds.

"They'll come up to you and whisper stuff that doesn't make sense," she recalls. "There was one woman telling us she was from Russia. Talk about unsolicited information – we didn't ask to know that. You're trying to make us react. We know what they want: destruction, chaos; they want to see it burn."

Sometimes, she says, they pause in one place trying to start a new chant or change the mood; if nothing happens, they move elsewhere and try again. "They're over here screaming 'black lives matter' and then they're over there bumping into teenagers and trying to incite riots."

Why Hawaiian shirts? As often happens in internet culture, the already-ludicrous "boogaloo" has since evolved, via puns and half-rhymes, into a kaleidoscope of codewords and symbols. So boogaloo becomes "big Luau" – a traditional Hawiian party, often featuring roast pig – or "big igloo", which has led to the adoption of igloos as a kind of heraldic emblem (Steven Carrillo's body armour had a igloo patch).

This playful propaganda – or "memetic warfare", as some boogalites only half-jokingly call it – is one key difference between boogaloo and the older militia movement, whose ideas it often recycles.

DeCook argues that boogaloo often merely echoes the philosophy that drove Gulf War veteran Timothy McVeigh to murder 168 people in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. "If McVeigh was alive today he'd definitely be wearing a Hawaiian shirt," she concludes.

On the other hand, Jones says boogalites have "set themselves apart" through their use of social media to recruit younger Americans, whom established groups – now mostly comprising baby boomers and ageing Gen-Xers – had so far failed to entice.

"There's quite a bit of evidence that the boogaloo movement is some people's first experience with political extremism," he says.

'This isn't the dark corners of the internet'

All this has made it harder for tech firms to monitor and identify boogaloo believers. Facebook is currently tracking more than 50 derivative terms of "boogaloo", and has had to train a special group of content moderators to keep up.

Though its powerful AI systems find and wipe out millions of examples of terrorist propaganda every month, it has so far been unable to build a boogaloo-hunting equivalent.

For boogaloo groups, this is probably the point. Beeson says they tend to present a "coded, acceptable narrative" on mainstream social networks, redirecting any "strategic or sensitive" subjects to an encrypted or anonymous alternative.

The result has been a successful digital marketing strategy in which big sites are used to "groom or recruit people to the cause" with what Beeson calls "adjacent content" – jokes and memes that avoid open propaganda while still reflecting boogaloo ideology. One study found that in the 30 days after America's first lockdowns, 36,117 people joined boogaloo-related Facebook groups, doubling their total membership.

In some cases, social media algorithms actually helped out by automatically recommending boogaloo content to potential followers, using the same targeting and profiling systems that have made them a fortune in advertising money. Though Facebook has now stopped such recommendations, DeCook believes the damage may have been done.

"Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have all been really slow," she says. "This isn't the dark corners of the internet. Your 11-year-old is pretty well exposed to white supremacist content via YouTube and TikTok. I think a lot of people don't want to confront that reality, but it's the case."

A dangerous powderkeg

With no leaders and little ideological agreement, the future of boogaloo is volatile. Jones says the community is "having a bit of an identity crisis": some members are die-hard racists, while others claim Black Lives Matter as natural allies. A few have declared themselves socialists, though this is probably misdirection.

“If there was ever a time for bois to stand in solidarity with ALL free men and women in this country, it is now," one Facebook group administrator wrote after Floyd's death. Others appeared to celebrate the idea of business owners shooting black protesters.

This very disunity may be boogaloo's most dangerous quality. Jones argues that its mix of "shifting and competing ideologies", coupled with its very real interest in violence, creates especially fertile soil for spontaneous terrorism and recruitment by more organised groups.

Even as America careens towards a highly-charged presidential election, boogaloo could fizzle out. But Jones believes it could also be co-opted by its most extreme elements and marshalled towards coordinated bloodshed.

DeCook further warns that the subculture includes "a high number" of military veterans or even active service members, and that many come from affluent families with funds to spare. Boogaloo-sympathetic YouTubers, she says, often have very professional recording equipment.

And Joan Donovan, director of Harvard University's media research unit, fears that some coverage of boogaloo has come "dangerously close to validating this small group". Its surreal trappings are part of a now-common far-Right tactic of using the absurd or unexpected to attract media attention and inject their symbols into the mainstream – which is part of what they mean by memetic warfare.

Meanwhile, boogaloo believers continue to make themselves known at protests, and to plot real violence. Some activists fear an outburst of violence on July 4, when a large number of marches are planned to coincide with America's independence day.

Ashley Dorelus, for one, is sceptical of boogaloo's help. "If you're here for Black Lives Matter, just put down your boogaloo," she says. "Don't bring your s--- to the fight." She does, however, agree on one point: "As much as people don't realise, the civil war is happening right now. It's happening right now."

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance