From Russia with schmaltz: Moscow’s answer to Tate Modern opens with a Santa Barbara satire

First Vladimir Putin came to visit. Then, for the second day in a row, the artists were turfed out of GES-2, a prestigious new arts centre built in a disused power station, as police and men in suits swarmed in for what looked like another VIP guest.

Instead of our planned walkthrough, I trudged through the snow to catch up with Ragnar Kjartansson, the star Icelandic artist headlining the art centre’s opening by re-filming the popular soap opera Santa Barbara as a “living sculpture”. He had taken a booth in the nearby Strelka Bar and was taking the disruption in his stride, despite it coming one day before the grand opening.

“We’ve been working on this for three years. We’re ready,” laughed Kjartansson, sporting a green neck scarf over a jean jacket. He keeps his mask on while we speak indoors. “It’s almost like a weird blessing. A breather before it begins.”

This is the triumph of one of Russia’s richest men, Leonid Mikhelson, opening his marquee cultural hub just a stone’s throw away from the Kremlin. Estimated to have cost in the hundreds of millions of pounds (he won’t reveal the exact amount), the pricey transformation of the 1907 power station is about more than just art, seeking to showpiece Moscow’s place as an international cultural hub and his V-A-C Foundation (named for his daughter, Viktoria) as its premier institution.

Set on the Bolotnaya embankment of the Moskva River, the 20,000 sq metre space sits inside of a hydraulic power plant renovated by the workshop of Italian architect Renzo Piano. Its new glass roofing, which bathes the building’s nave in light, could recall a botanic garden save for the Matisse blue pipe chimneys stretching 70 metres into the sky.

When Putin arrives, he is met by Mikhelson, and the cofounder of V-A-C, Teresa Iarocci Mavica, who launches into a talk on the centre’s roots in Houses of Culture meant to educate the public and dwells on the inaugural season’s theme: Santa Barbara. How Not to Be Colonised?, a call for cultural dialogue on equal footing through a “reappropriation” of the American soap opera that became a Russian hit.

It feels like a mission statement with a dab of politics for Moscow’s new premier art space, the Russian establishment’s answer to the Tate Modern or Centre Pompidou in Paris (also designed by Piano). Compared to the raw aesthetic of the Geometry of Now music festival in 2017, which featured a sound-based installation with recordings of prawns having sex and a lecture on gender, politics and sound by a transgender musician, it all feels far more manicured, considered, and safe.

All the better, as this was something of a pitch meeting. “I asked [Putin] for his support. He looked at me and said, ‘How could I not support a project as great as yours’,” Mavica tells me Putin said to her after they finished his walkthrough. “It’s the most important thing, it’s important for us to receive that legitimisation.”

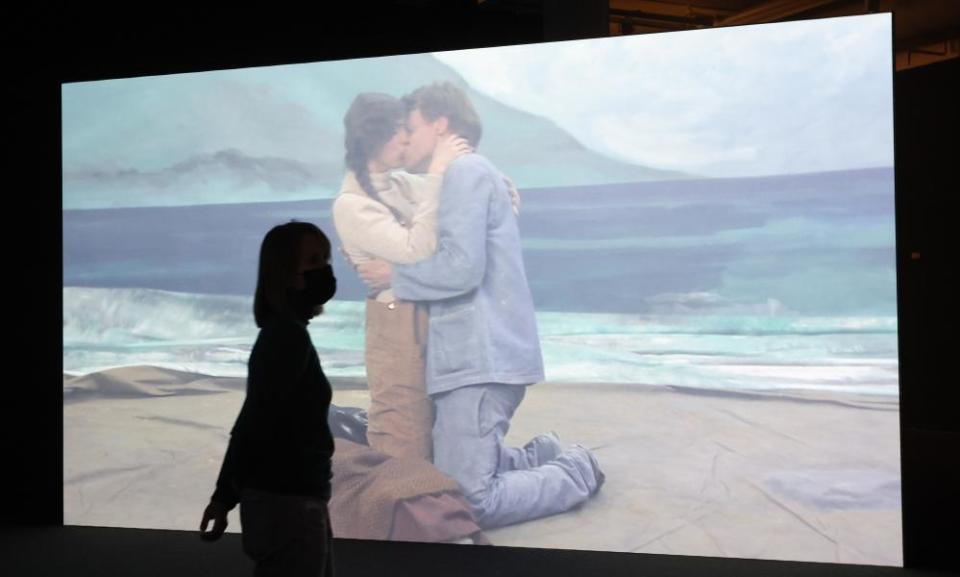

That inaugural season is driven by the sensitive direction of Kjartansson, who is creating a “living sculpture” by re-staging, filming and editing 98 episodes of Santa Barbara, the soap opera that became a cultural phenomenon in 1990s Russia. Inspired by a Foreign Policy article about Santa Barbara’s influence on the former Soviet Union (there are housing developments modelled on the show), the exhibition also touches on the obvious tensions between east and west.

“I’m an Icelander living right between Moscow and Washington. Put your finger in the air and feel how the relationship’s going … I just find some kind of poetic beauty in this project because of that,” he says.

In Russia, the phrase Santa Barbara has become a kind of joke, meaning a tangled family relationship that it’s better not to get involved in. But Kjartansson says the work is deadly serious, paraphrasing Björk that “every song she writes starts as a joke and then she carves away until she finds the truth in it”.

“It’s about traumatic times in this country and in world history. And reenacting them in this way,” he says.

I ask him why he decided to call that “colonisation”, to me a provocative description that speaks to Russia’s interpretation of being taken advantage of in the 1990s. It turns out he hadn’t. “How not to give in to colonisation was totally from Teresa,” he said. “It has not been my thought. I’ve never ever thought like this is about cultural colonisation or cultural dominance, it’s just about cultural influence.”

As Kjartansson notes, you can’t control how people will interpret your art. It’s clear he feels a warmth for Russia stretching back to his first visit in the mid-1990s and the art selected for his and Ingibjörg Sigurjónsdóttir’s exhibition To Moscow! To Moscow! To Moscow! – which opens GES-2 – speaks to that tenderness.

He describes how he carefully recreated a scene from the opening of Russia’s first McDonald’s for a photograph, rhapsodises over Olga Chernysheva’s black-and-white photographs of truck drivers trapped in traffic jams, and swells with pride at bringing the original Dimmalimm, the Icelandic fairytale about a prince and a swan, abroad for exhibition for the first time.

That raw enthusiasm and accessibility is what GES-2 was seeking when it chose Kjartansson to headline its opening season, said artistic director Francesco Manacorda, formerly of Tate Liverpool. “His pieces are emotional magnets,” he said, pointing to his 2012 video installation The Visitors, which the Guardian named its best artwork of the 21st century.

Through Strelka’s windows we have a view on the golden-domed Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, where Pussy Riot filmed their Punk Prayer in 2012 and were subsequently imprisoned. When I ask Manacorda to what degree they’re ready to discuss explicitly political themes, he said he would “avoid it as the centre stage … Our field is culture. There will be elements that will have political resonance. But I don’t want to become a thinktank. I don’t want to be a sort of political organisation.”

GES-2 House of Culture opens to the public on Friday as hundreds of journalists, bloggers, critics, artists and others descend on Balchug Island for a walkthrough and then an evening party. There, I catch sight of Mikhelson, the billionaire founder and head of gas giant Novatek, passing through the crowd with his daughter Viktoria, who also works for the foundation. He has declined interviews ahead of the opening and gives no speeches.

Earlier that day, the Russian actors donned their tuxedos, ball dresses and pearls as they began filming their first scenes from Santa Barbara, filmed first on painstakingly recreated sets, then beamed over to an open-space editing room, and finally on to televisions showing the final product.

Thirty years ago, these Santa Barbara sets were how Russians imagined the good life. Now, judging by GES-2, aspirations have grown loftier. When I asked what Russians saw in an American soap 30 years ago, Bridget Dobson, one of the show’s writers, had a quick response: “They saw themselves.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance