'Sexism stands at the door': 11 female film-makers written out of mainstream Hollywood history

Everything we’re told about cinema is that it’s shaped by men. If women feature at all in many Hollywood histories, it’s to look gorgeous on screen and lead interesting personal lives off it.

But this narrative has been warped, consciously and not, by the men who have dominated film-making for almost a century, ignoring the women who made films, challenged the studio system – and helped bring it down.

The battle for equality on the screen is still being fought. Things are slowly changing for the better – witness Chloé Zhao’s victory at Sunday’s Golden Globes – but it comes too late for generations who have been locked out of Hollywood’s corridors of power. Their stories are still too-little discussed. Here are 11 women whose ill-treatment illustrates Hollywood’s alternative history

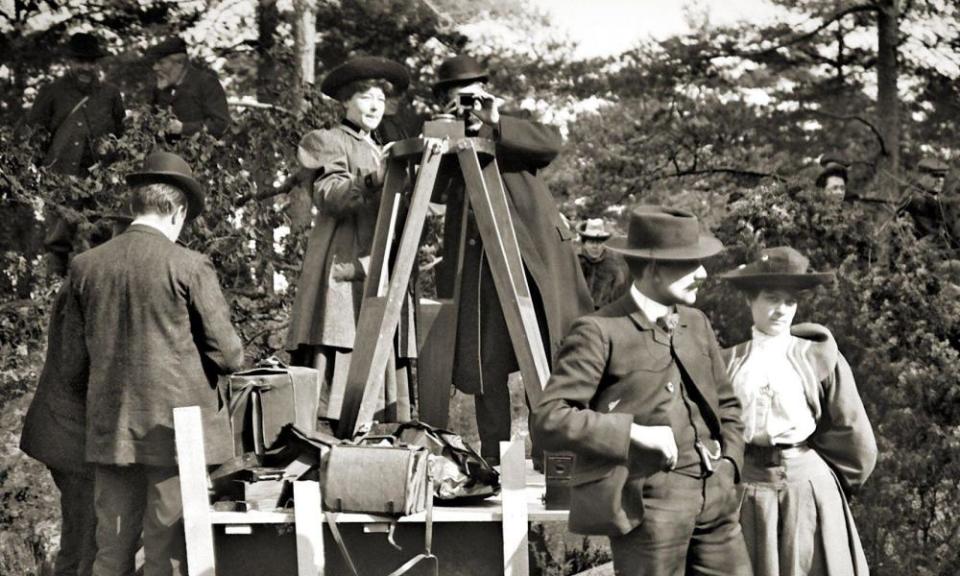

Alice Guy-Blaché: the silent era director whose set was chopped up for firewood before she could shoot

As a 22-year-old secretary to French film magnate Léon Gaumont, Alice Guy-Blaché was one of the first people to pick up a camera and make a narrative film, 1896’s The Cabbage Fairy. She soon became Gaumont’s head of production and made hundreds of films, showcasing the company’s experiments with colour and early synchronised sound before high-profile features such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame. But when her department became profitable in its own right, instead of a mere advertising arm for the company’s products, she faced attempts to replace her and had to appeal to the board (led by Gustave Eiffel) to save her job.

Her staff then moved to outright sabotage, chopping up a completed set on her film The Life of Christ for firewood. Undeterred, Guy moved to the US with her new cameraman husband Herbert Blaché and set up her own studio, Solax. She had considerable success until the twin blow of a divorce and the Spanish flu took her out of the picture. She was erased from Gaumont’s official history and – like many of her female peers – spent the rest of her life fighting to preserve her films and reputation.

Mabel Normand: silent film legend and Chaplin’s mentor destroyed by the scandals of male friends

The classic silent-movie image of a girl tied to train tracks in the path of an oncoming train is sometimes used to ridicule the whole era. But that image comes from Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life (1913) and was itself a parody: the girl was Mabel Normand, and she was poking fun at stage tropes. A veteran of more than 100 films, Normand was a star at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios and a writer and director. She took a promising newcomer called Charlie Chaplin under her wing at the start of his film career and taught him how the artform worked, co-directing much of his early work. She later formed a production company and made Mickey, the biggest film of 1918.

But men eventually brought Normand down. She was caught in the swirl of scandal that destroyed the career of her friend and colleague Fatty Arbuckle in 1921, and was later a suspect in two murders committed by male acquaintances. Each scandal saw more of her films pulled from distribution, until she was effectively washed up and much of her legacy diminished. Unlike Sennett and Chaplin, she never got to write a self-aggrandising memoir to boost her legacy – but then again, by that time there was no market for such stories from women. Alice Guy-Blache and star-director Nell Shipman both wrote autobiographies and found no takers in their lifetimes.

Lillian Gish: “not a particularly strong directress”

A frequent leading lady for DW Griffith, Lillian Gish was a huge star of the 1910s. Less well-known is that she was also a director, of Remodelling Her Husband (1919). Gish set out to make the film a proto-feminist statement. She hired as many female crew as possible, wrote the script with her sister and leading actor Dorothy Gish, and brought Dorothy Parker aboard for the intertitles. Despite a freezing studio (the boiler broke) and unrelenting hostility from her cameraman (the one key role for which she hadn’t been able to find a woman), Gish got her film made.

Griffith was complimentary and the film made 10 times its budget at the box office, but the reviews were not all kind: Variety decreed that she was “not a particularly strong directress”. In the aftermath, Gish said: “I am not strong enough [to direct]. I doubt that any woman is.” Already, by 1919, the idea that you had to be a big strong man to direct was taking hold, even among women ambitious enough to try directing themselves. By the time the sound era dawned, almost all female directors had disappeared: Dorothy Arzner would be almost unique as a film-maker during the next 20 years.

Gloria Swanson: forced into a dangerous and illegal abortion

Swanson was a rare silent star who made the leap to sound successfully, but a couple of years before she did, in 1925, she found herself in an awkward contractual position. In Paris for a lengthy shoot, estranged from her second husband but not yet divorced, she had started dating the man who would become her third. She became pregnant, and anyone with a calendar could tell that the child was not legitimate. Her studio wanted her to have an abortion, and they had a trump card: Swanson had signed a morality clause that made her employment contingent on, among other things, not having sex outside marriage. If she had the baby, she would obviously have been in breach and would forfeit her entire income. This was not an unusual studio tactic at the time: they didn’t want either ingenues or sex symbols to spoil their image by getting pregnant.

But Swanson’s abortion, illegally carried out in a Parisian hotel, was botched. She hovered near death for days and complained later that the studio even profited from her illness, publicising her (unspecified) battle for health and keeping fans agog for news. That was the way under the studio contract system: manage lives to a startling degree, because the lives of stars translated directly into profit.

Lena Horne: a black woman confined to roles that could later be cut

Women of colour faced much tougher career battles than white women. Horne was a stunning beauty and an accomplished singer when she was signed to a contract with MGM in 1942, but the studio struggled to find major roles for her. The Motion Picture Production Code that governed film content was racist from its inception, and barred any depiction of interracial romance. In 1949, Horne hoped for the leading role in Pinky, an Elia Kazan race drama about a young black woman who passes as white, but because the character has a white boyfriend that role went to a white actress instead, to sidestep the Code. Since there was also little appetite to make all-black films (despite the success of Hallelujah in 1929, for example), women including Horne were largely confined to roles as prostitutes, maids or – if they turned down the first two, as Horne did – single musical scenes that could be excised from the film prior to its release in the southern US states. It’s the same dynamic seen today when LGBT references are cut from films prior to their release in China or the Middle East, as happened to Bohemian Rhapsody.

April Ashley: a transgender actor who starred with Bing Crosby

Hollywood studio timidity and the Production Code meant that there were few LGBT stories before the 1960s, and those that existed were treated rarely and obliquely. That was the scene when, in 1961, transgender woman April Ashley landed a role in the Bing Crosby and Bob Hope film The Road to Hong Kong, over 400 applicants. It was a major milestone for the model turned actor – but a friend sold her story to the Sunday People, who outed her as trans. Her credit was dropped from the film and her career was stalled at its inception. Another transgender model-turned-actor, Caroline “Tula” Cossey, would experience the same ordeal 20 years later after she got a tiny role in For Your Eyes Only, this time thanks to the News of the World. Hollywood, and the media, have at least begun to move on from attacking trans people in such a transparent way, but there are still no out male action stars, for example, which suggests that LGBTQ+ identities are still seen as a career limitation by Hollywood, and only a minute number of trans actors can claim more than a handful of film roles.

Jean Seberg: humiliated and martyred on screen – and off

Tales of Hitchcock’s controlling and sometimes abusive behaviour towards his female stars are legion, while the women endured it as the price of the great roles he also created. But he was far from alone in bullying leading ladies. Otto Preminger was so famously tough that Joan Crawford – a relative fan – called him a “Jewish Nazi”. When he set out to create a star for his film Saint Joan and chose Jean Seberg for the role, he oversaw every aspect of her life, controlling her meals and putting her in a suite directly below his own during shooting. He humiliated her on set and, when she was burned during the filming of Joan’s martyrdom, he crowed: “We got it all on film.” It’s the sort of obsessive and dictatorial behaviour that is often seen as proof of artistic genius, but elevating brutality as an acceptable and maybe even desirable cost of doing business is one that fed the atmosphere of exploitation and ill-treatment in Hollywood that led to #MeToo.

Maya Angelou: “racism and and sexism stand at the door”

In the 1970s, the “New Hollywood” of Coppola, Scorsese, Altman and the rest seemed to open new possibilities for storytelling in film. But as usual the main beneficiaries were white men. Maya Angelou – already a Pulitzer prize nominee and soon to be a Tony award winner – wanted to direct her script Georgia, Georgia in 1972. Expecting opposition, she studied cinematography to enhance her campaign. But she was not given the chance to make her debut: the script went ahead with a male director, Stig Björkman, who had one film more experience. “In film, racism and sexism stand at the door,” she said of the experience, as she realised she would have to be “10 times more prepared than my white counterpart”. Another black female director, Gina Prince-Bythewood, made the same observation in 2020. Angelou made her directorial debut 26 years later, with Down in the Delta (1998). Black women still comprise only about 1% of feature film-makers.

Selby Kelly: animator told “women have no sense of timing”

Animation has some of the thinnest excuses for its lack of women. Animator and artist Selby Kelly applied for an animating job at Disney to work on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but was told that women had “no sense of timing” and couldn’t be animators. In those days, the only women allowed inside the animation building were reference models. Kelly worked as a paint mixer on the film instead. The sexism became so ingrained at Disney that the animators “didn’t even notice any more”. The Disney-fostered disparity largely remains in place across many animation studios today: although animation courses see a roughly 50-50 gender split and have done for decades, Pixar’s first solo female director was on short film Bao in 2018, and their features have had none.

Dawn Steel: Top Gun executive ousted from Hollywood only to make a comeback

Hard-drinking, hard-swearing Dawn Steel became president of production at Paramount in 1985, only the second woman in Hollywood to hold such a position since the silent era. She greenlit hits such as Top Gun, Fatal Attraction and The Accused – before being fired by her male bosses while she was in labour with her daughter. To be a woman in a Hollywood boardroom was to have a target on your back. As one of Steel’s predecessors, Sherry Lansing, was warned when she was made president of production at Columbia Pictures in 1980: “You represent all of us … You have to succeed more than anyone has ever succeeded.” Steel made a comeback, however: six months later she was appointed head of Columbia, where she released films including When Harry Met Sally and Ghostbusters 2.

Catherine Hardwicke: described as “difficult” and “emotional”

Hardwick’s adaptation of young adult novel Twilight made $400m on a $37m budget. But before the film was released Hardwicke had been described as “difficult” and “irrational” by studio executives in the press, and she was not invited to direct the sequel. This lack of a career bump following a success seems to afflict female directors far more often than men. Mamma Mia!, Wayne’s World, Twilight, 50 Shades Of Grey: all hit films by women, all replaced by men for the sequel. It took several months of negotiation before Patty Jenkins signed on to the sequel to 2017’s Wonder Woman, largely because she wasn’t immediately offered the same sort of compensation bonus as a man in the same position. Hardwicke’s difficulties seemed to come from a brief weep during a tough day. “Emotional is a code word,” she said. “If a man does it, he’s so passionate. If a woman does it, she’s too emotional.”

• Women vs Hollywood: The Fall and Rise of Women in Film by Helen O’Hara is published by Robinson (£18.99)

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance