Shareholders can't force businesses to act morally. But governments can

Mark Carney stuck it to laissez-faire capitalists in his Reith lecture last week. There has always been a moral dimension to selling stuff, the former Bank of England governor told any listening free marketers. Their own bible would tell them so.

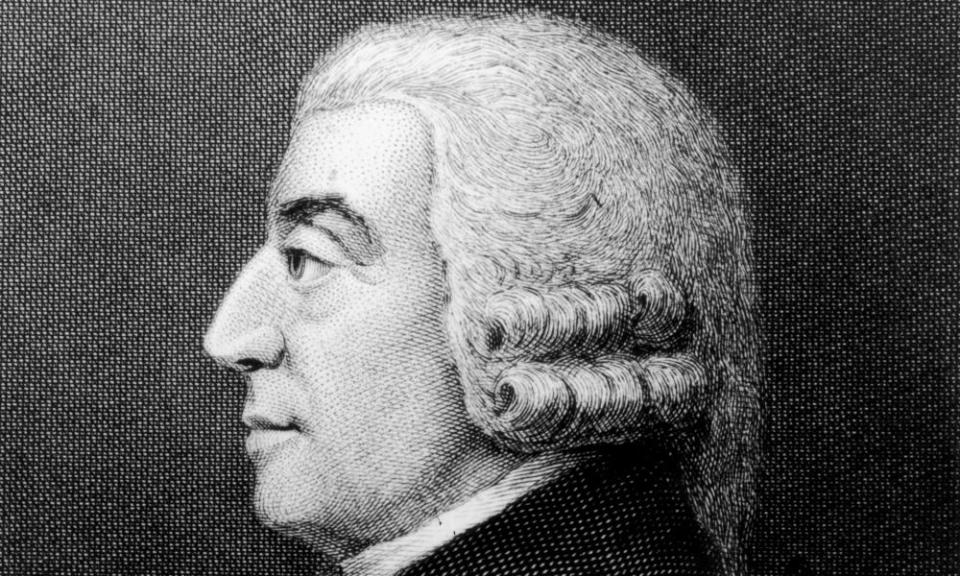

The bible in question was written by Adam Smith, the 18th-century Scottish moral philosopher and economist whose phrase “the invisible hand” is trotted out by every pro-market evangelist keen to justify the idea that governments should let businesses get on with selling, unfettered except by the most basic regulations.

Milton Friedman, the monetarist guru to Margaret Thatcher’s top advisers, was cited as wantonly abusing Smith’s arguments – though there were many others still making a living in the world’s rightwing thinktanks who perpetrated the same misreading, Carney said.

Smith used the phrase just once in his most important book, The Wealth of Nations (and only three times in his entire canon). But he devoted many pages to the need for an active state and, after observing their effects on fellow humans, the idea that rich owners of capital should observe a higher morality that circumscribes their activities.

Economics, far from being a branch of mathematics, as it is so often defined in British universities, was, Carney said, guided by the philosophy of the age and was therefore deeply political.

Carney believes forcing companies to be transparent gives shareholders the ammunition to impose moral obligations on the managers of their assets

Smith lived in a religious age and appealed to the charity of his readers. Without religion, chief executives have only the profit motive and the bonus to guide them. And with capital often in the hands not of a single owner-manager but of millions of shareholders, it is less clear to voters and the public at large how Smith’s moral sentiments can be translated into action today.

This question is especially important as Britain readies itself for leaving the EU’s trading bloc. Whether a deal is struck or not, Brexit is underpinned by a neoliberal belief that the “neutral” market needs to reassert itself away from interfering Eurocrats. That is the majority view among British voters, whatever leftist Brexiters believe, and certainly it is the government’s view, a nod to climate change notwithstanding.

Carney believes that forcing companies to be transparent about their strategies and the impact they have on stakeholders – staff, the community, the environment – is an important complement to government action, giving shareholders the ammunition they need to impose moral sentiments on the managers of their assets.

The flaw is that shareholders are a distant and disconnected bunch. They include the endowment funds of private schools, universities and wealthy individuals, the sovereign wealth funds of oil-rich nations and the western pension funds that represent hundreds of millions of savers, most of them petrified about a drop in retirement income. These are not the people to take action – at least not in their role as investors.

A growing number of rich people want to “do good” with their billions. Bill Gates is a classic example of someone who has spurned superyachts in favour of spending on health remedies for the world’s poorest. Yet he is a single-issue donor, focused on malaria, polio and, lately, Covid-19. What Carney is addressing, even if his solution is flawed, is a broader malaise.

Last weekend the Swiss voted in a referendum that would have allowed victims of alleged human rights violations or environmental damage to sue Swiss companies in Swiss courts. According to the proposed law, companies would need to prove they had taken all necessary measures to prevent any harm.

After 10 years of campaigning, first by a group of seven civil bodies including Amnesty International and, since a reboot in 2016, by a coalition of 450 organisations from churches to environment groups, the Responsible Business Initiative achieved 50.7% of the vote, but then failed to secure a majority in every Swiss canton.

Swiss business leaders, some of them facing accusations of exploiting child labour, burning rainforests and polluting rivers, saw that the RBI would make them liable for the actions of independent suppliers. They backed a more moderate version, which the government adopted, that forces companies to strengthen scrutiny of their own operations and suppliers overseas.

This amounts to just another form of self regulation, which cannot succeed when companies, under pressure to drive up profits, would be taking actions that increase their costs. Only cross-party, popular action, forcing governments to impose rules on corporate behaviour, can inject some morality where so little manifestly exists.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance