Shopping centre owner Intu could have saved itself years ago

If you want to see how complicated it is possible to make the financing of an owner of shopping centres, have a trawl though Intu’s annual report for 2019, which could be its last if knife-edge talks with lenders go badly in the next few days.

Related: Trafford Centre and Lakeside owner warns it could go bust after £2bn loss

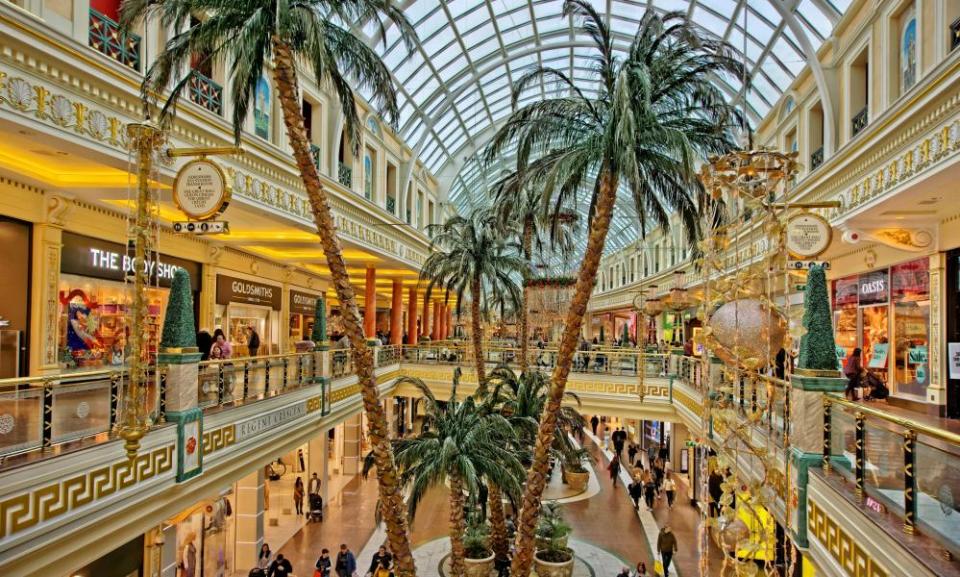

Skip the pictures of happy shoppers at the Trafford Centre, Metrocentre and Lakeside, obviously. And definitely ignore the guff about “surprising the visitors of tomorrow and delighting the customers of the future”. Intu’s crisis is in the here and now.

Four main property companies sit beneath Intu plc, which is essentially a holding company, but there are other vehicles. The list of subsidiaries, joint ventures and associate companies runs to four and a half densely printed pages. Total group borrowings of £4.5bn comprise the aggregate of 21 separate instruments, with most of the debt secured on individual or several properties.

So when Intu talked on Tuesday about seeking agreement from “relevant financial stakeholders across its structures, at both the asset and group level,” it’s referring to a large number of investors.

In theory, you’d assume they would have a common interest in avoiding an administration and seeking an orderly debt-for-equity swap. It would, for example, be counterintuitive to pull the plug at a moment when non-essential shops are reopening; Intu’s projections already assume a 37% plunge to £310m in rental collection this financial year across 14 centres.

In practice, nothing should taken for granted. One problem is that cash in one part of Intu often cannot be used elsewhere; that may create an incentive for some lenders to try to rip their asset out of the corporate structure. Then one has to consider the usual pass-the-parcel debt games; opportunistic hedge funds may prefer a quick resolution instead of a standstill period on debt repayments of more than a year.

The talks could fail, in other words, which is merely to state the obvious given that the current waiver of covenants on a vital £600m credit facility, provided by seven big banks, expires on Friday.

Whatever happens, Intu’s crisis cannot be blamed on Covid-19. It’s been years in the making. The company owns nine of the 20 largest shopping centres in the UK, as management points out frequently. It’s meant as a boast about the underlying value of the assets, even in the era of online shopping. Really, though, it’s an indictment of the failure to fix an over-leveraged balance sheet when the opportunity existed.

Intu could have saved itself years ago, when the share price was steady at 300p-ish from 2010-17, versus today’s 4.4p. Only the board members – especially deputy chairman John Whittaker, whose Peel Holdings is a 27% shareholder – can explain why equity was never raised or why more assets weren’t sold earlier to reduce risk. The desperate (and failed) scramble to find £1bn-plus earlier this year came far too late.

From outside, one can only diagnose delusional belief that a shopping centre portfolio could never fall in value by a fifth, as Intu’s did last year. Others are guilty of excessive optimism, but Intu’s unique contribution has been extreme financial leverage. The debt-to-asset ratio was 68% at end of last year in a market where 40% is usually considered racy. The crisis was born in the boardroom.

Pay revolt looms at Tesco

Tesco’s annual meeting falls on Friday, and there’s a chance the pay report will be voted down. If not, the rebellion will be substantial. Investors (or a chunk of them) tend to hate any moving of goalposts for bonus purposes, and Tesco’s manoeuvre was brazen.

The remuneration committee simply removed Ocado, and its soaraway share price, from a comparator group of peers in a long-term incentive scheme. The effect was to boost chief executive Dave Lewis’s pot by £1.6m and finance director Alan Stewart’s by £900,000.

Related: Tesco sells up in Poland to focus on UK

Ultimately, it matters little whether the revolt is 45% or 55% or any other figure. The vote is an empty advisory affair, meaning Tesco is free to ignore it, aside from issuing some equally empty words about maintaining good relations with investors.

The stylish thing for Lewis to do at this point, though, would be to capitulate. He’s done a better job than Tesco’s pedestrian share price would suggest, but he’s also been paid £29m during his six years in charge. He doesn’t need to scoop the last serving in shabby circumstances.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance